Glenda Hawley1, Anthony G Tuckett1

Purpose: This study aims to offer guidance to lecturers and undergraduate midwifery students in using reflective practice and to offer a roadmap for academic staff accompanying undergraduate midwifery students on international clinical placements.

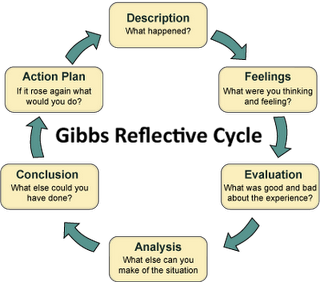

Design : Drawing on reflection within the Constructivist Theory, the Gibbs Reflective Cycle (GRC) provides opportunities to review experiences and share new knowledge by working through five stages-feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion and action plan.

Findings : The reflections of the midwifery students in this study provide insight into expectations prior to leaving for international placement, practical aspects of what local knowledge is beneficial, necessary teaching and learning strategies and the students' cultural awareness growth.

Implications : The analysis and a reflective approach have wider implications for universities seeking to improve preparations when embarking on an international clinical placement. It can also inform practices that utilise reflection as an impetus to shape midwifery students to be more receptive to global health care issues.

Keywords : midwifery, students, reflection, international placement, education, learning, culture

1 The University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia

Corresponding author: Glenda Hawley, School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland 4072, Australia, [email protected]

Within the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at the University of Queensland (UQ), Australia, the curricular conceptual framework utilises the constructivist theory of learning and teaching (Narayan et al. 2013). This theory informs both the educational and philosophical frameworks for course content within the school programs and advocates that students engage with information to construct knowledge. An imperative component of the theory is to critically reflect on past and recent experiences and actively use these reflections to construct new meaning and knowledge (Narayan et al. 2013).

It is known that reflective practice is useful to assist health care providers to link experience with theory. There is ample support for reflection as an essential part of learning in nursing and midwifery studies as it empowers decision-making, acts as a mechanism to improve patient care and benefits professional development (Wain 2017). In addition, reflection is also considered an important component in helping practitioners critically consider, validate and inform actions to improve practice (Lincoln 2016).

Reflection has also become a major part of continued professional development. National Governing body websites for nurses and midwives, that incorporate professional development now include lessons on the 'art and science' of reflecting and contemplating on practices in midwifery (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2016; Wilding 2008). Relying on reflection, midwives in Australia are required by the national regulatory body of their profession-the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australi-to record evidence of currency of practice in a yearly portfolio and it is mandatory for them to maintain an acceptable level of competency to fulfil regulatory requirements (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency 2019). The Royal College of Midwives in the United Kingdom (UK) also recognises reflection as beneficial in experiential learning and for the development of critical thinking skills, which helps to facilitate the integration between theory and practice (Regulators unite 2019; Tuckett & Compton 2014). However, good exemplars of reflective practice and what this might look like can be hard to find. In midwifery literature, authors commonly use a descriptive format to write about reflection occurring around an incident and their experiences (Lewis 2017). Reflection is exemplified in overseas placements but again, the context is usually descriptive and observational and may only discuss the feelings of participants (Lewis 2017). Since descriptive reflection has been typified as merely stating what happened or as an exercise in ticking boxes (Koshy et al. 2017), more in-depth data into reflective thought processes are required. A higher level of reflection occurs when more meaningful questions are asked, such as 'what happened?', 'why does it matter?' and 'what are the next steps?' Answering these questions is important for learning and necessary for change to occur (Koshy et al. 2017). This higher-level quality reflection can occur when a model or a process such as the Gibbs Reflective Cycle (GRC) is used (Gibbs 1988).

In relation to this, reflection plays a crucial role in the field of health care education, especially since sending students on international clinical placements is considered important to build capacity for health professionals in a global health care sphere (Tuckett & Crompton 2014). The key objectives for students attending an international clinical placement include: being immersed in a culturally-diverse environment, developing resilience, recognising norms and differences, learning to live outside their comfort zone, leveraging opportunities after graduation, and developing a sense of helping others (Tuckett & Crompton 2014). While the number of students participating in international placement is increasing, there is a paucity of information on what specifics are involved in the planning of such a project.

In this study, the first author used the GRC to provide her firsthand accounts of students' expectations prior to leaving, the practical and beneficial aspects of having local knowledge, planning and preparing the necessary teaching and learning strategies, and changes to students' cultural awareness. Since reflection is perceived as deliberate thinking and a process of looking back, it is acknowledged that it can be used to examine competence and preparedness to improve future practice (Nilson 2011). This paper contributes to the field of study in two ways: (i) by filling the gap in knowledge on how to prepare students for an international clinical placement, and (ii) by offering a transferable example of the use of the GRC that can be applied in the classroom.

In September 2017, UQ offered its undergraduate midwifery students an opportunity for international clinical placement to India. The placement was funded by the New Colombo Plan, which is an Australian Government initiative that supports undergraduate students in their studies by helping them to participate in residencies or placements in the Indo-Pacific region, with an aim to enhance the students' knowledge of cultural practices in the region (Australian Government 2018).

While the placement was designed to at least be an observational experience, students had the opportunity to participate in patient care while being assisted by a local midwife. The program was for students who were in their second or third year undergraduate degree studies, which meant that they were equipped with having learnt the essential skills in managing normal birth and newborn care, including common complications. The timing of the placement was considered ideal as (i) the students had had at least one and a half years of clinical placement exposure, which enabled them to utilise knowledge and skills during the experience in India, and (ii) the students had a subsequent final-year clinical placement upon their return to Australia.

The application process was rigorous, involving an expression of interest letter and an interview, which included questions scored numerically to ascertain the motivation for wanting to embark on an international placement (MaRS Discovery District 2019). The interview also presented the students with an introduction to avenues for raising money to 'give back' to the facilities the students were to visit. Successful applicants were invited to attend an introductory educational workshop to inform them of placement expectations and give them opportunities to ask questions.

It is also worth noting that by the time students have progressed through the recruitment process, they were well aware that the expected, formal teaching and learning that was part of their home university experience would continue in India. This includes learning through the Problem-based Learning (PBL) teaching approach as the Midwifery program at UQ utilised this method of learning, which has been shown to be beneficial in helping develop student compliance (Da Silva et al. 2018). This approach has been used in many medicine, nursing and midwifery settings (Da Silva et al. 2018; Rowan et al. 2008). In midwifery PBL, a case scenario is presented with accompanying 'triggers' identified to provide a topic for students to research and present back to fellow students in class. The 'triggers' are broad and include topics such as antenatal care or instrumental births. This differs from medicine programs where the 'triggers' used in such exercises are usually directly related to a specific case (Rowan et al. 2008). The midwifery format lends itself to ensuring that all students are able to relate to the broad topic and then critically relate the case to the topic when asked during question time in their presentation. In practical terms, PBL usually requires some form of visual stimulus, such as utilising a video in PowerPoint slides to present information. This form of presentation requires a reliable internet connection.

This paper demonstrates how one midwifery lecturer (the first author) used the GRC to describe the experiences and lessons learnt when mentoring midwifery students on an international clinical placement to India. The larger goal of this paper is to offer a real-world primer for other midwifery lecturers and undergraduate midwifery students to guide their own reflective practice.

Ten undergraduate midwifery students took part in this study. The placement extended over four weeks in the south of Karnataka, India. The first two weeks were spent in a 50-bed hospital in a rural community, and the final two weeks were spent in a tertiary 380-bed hospital in a major city. The placement locations were chosen by a host who was a social worker connected to the Clinical Placement Office at UQ, who had local knowledge of the health care systems. A scoping visit to the hospital sites in India occurred nine months prior to the student experience. This scoping visit was an opportunity for the University staff to gain exposure in-country and meet with local senior health care staff to finalise details of placement requirements. The visit was valuable as the sites could explain and discuss expectations required from the placement. These included that the students be supported by the University supervisor but be allowed to perform skills with a clinician while remaining within their scope of practice. Details of accommodation, meal and transport preparations were also finalised.

The rural hospital operates a sustainable health care system that is owned by the community and managed by local tribal staff. Although small, the facility has departments including outpatient, surgical, medical, paediatric and obstetric units. Although a small number of births occur, approximately 94% of women give birth in this rural hospital rather than travel to a larger centre. Additionally, there are specialist services for sickle cell anaemia management, dental care, ultrasound, pharmacy and the blood bank.

This placement also provided an opportunity for students to engage in community development and health promotion and included visits to the only local primary school. Here, activities included teaching handball and playing outdoor games with the children. On community visits, the midwifery student group was immersed in assisting with the provision of primary health care activities, including recording of blood glucose levels, body measurements, foetal heart rates, early childhood checks and adult checks. The midwifery students were made to feel welcome. They were invited to a council meeting and festivals where local cultures and cuisines were introduced.

The tertiary city hospital also has the same services as the rural hospital plus high acuity units for dialysis, coronary, adult and neonatal intensive care. Additionally, in 2017, the tertiary hospital commenced a nursing school recognised by the State Board of Nursing in India, where obstetric nurses are trained. The tertiary hospital is managed by a religious congregation and provides both public and private services. A strong caring philosophy remains evident at the site through a vision of health and healing. The hospital has approximately 300 births per month, with antenatal visits occurring on site. Both hospitals offered opportunities to conduct health visits to communities to conduct postnatal and baby checks.

The placement aligns with the aim of students achieving their clinical practice experience to consolidate midwifery skills learnt in Years 1 and 2 of their undergraduate program. The expected international clinical placement outcomes include:

The GRC was adopted to critically appraise the experience of the project (see Figure 1). Wain (2017) affirms that the GRC is often used in higher education programs and that it affords students the chance to build on pre-existing knowledge. Additionally, the cycle portrays a mechanism of learning and informs future practice by systematically describing, analysing and evaluating learning (Wain 2017).

Figure 1. Gibbs' reflective cycle (Gibbs, 1988).

Gibbs (1988) theorises that reflection is needed to learn and that the experience alone is not enough. He espouses that experience can be quickly forgotten and hence, it is from the feelings and thoughts emerging from reflection that concepts can be generated and new situations can be approached more effectively. It was originally advocated that the cycle be used in repeated situations, which is why it is often applied to nursing and midwifery scenarios (Gibbs 1988).

A strength of the GRC is that although structured, the cycle provides enough freedom to add components and details specific to the situation (Gibbs 1988). In some quarters, this freedom is considered a threat to the process itself, since the ability to adapt the content means the reflection could be taken too lightly (Gower et al. 2017). However, this paper argues that this is outweighed by the model's flexibility and usefulness for tailoring the lessons learnt from one experience and applying these to another into the future. Subsequently, this is considered a scaffolded approach to lifelong learning (Gower et al. 2017). The GRC thus provides an ideal opportunity to reflect on and identify specific strategies needed to guide students when embarking on an international clinical placement.

In what follows, the first author relied on the GRC to critically appraise how midwifery students were managed while on an international clinical placement to India. Each of the five stages of the GRC are used as a mechanism to provide new knowledge to inform future international clinical placements and demonstrate a real-world application of the GRC that can be used in the classroom as an example to guide reflective practice (Watkins 2018).

The first author kept a diary in which daily entries were written, which included both description and appraisal of student activities in specific hospital units, the education provided and student concerns. The diary also served as a repository for the information that has been examined to provide the results of this study. The results of reflection using the five GRC steps-feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion and action plan-are expounded in detail here.

India was an unfamiliar destination to the first author. Despite having travelled extensively internationally and throughout regional/remote Australia prior to the placement, the first author was a little apprehensive about accompanying students on this placement. Preparatory workshops were arranged to showcase potential scenarios that students might likely encounter, and discussions were held with guest University staff who were of Indian origin and familiar with the Indian culture. However, a sense of the foreign and unfamiliar remained prior to departure.

There was also apprehension about how the students would interact with each other and with strangers as well as how they would ultimately cope with being away from home. Many of the students did not have prior shared classroom or clinical lessons or had work together, so to 'know each other' was imperative for making the placement succeed.

Although the first author could not ascertain internet reliability during placement, it was anticipated that connectivity would be limited. This mattered because a critical component of planning relied on the PBL 'triggers' being presented in a PowerPoint format. In anticipation of potential internet instability, learning resources now needed to be in paper format, such as using photocopied pages from texts and journal papers. Prior to departure, extensive planning was conducted around PBL topics. The 'trigger' topics were modified to accommodate scenarios of women in an Indian setting. This step was deemed to enhance the experience for students who could research the expected issues in the international setting and identify appropriate care.

Being chosen for the placement also gave the impetus to students to engage in fundraising projects to 'give back' to the community or hospital. The placement host assisted students in email communications with local nominated representatives, who responded with suggestions to the requests. This mattered because the students were initially keen to provide hard supplies, such as tympanic thermometers and oxygen saturation machines. While these supplies were important, consideration had to be given to battery shelf life and the availability of an electrical input as these were required to keep the equipment operational. The hospitals and community instead preferred smaller packs of birth products and cash donations. The rural community were very happy to receive play equipment for attending children and local community students. The midwifery students were pleased with these responses and proceeded to compile birth bundles comprised of a baby blanket and shirt, soap, nappy and moisturiser. There was extensive discussion about providing a disposable nappy but as these were easily available in India, the nappy option was dropped. The students raised A$1000 over eight weeks by conducting a sausage sizzle and bake sale at a local hardware store as well as an India Independence Day-inspired dinner with auction.

There were some reservations about how the midwifery students would engage with patients and staff in both the rural and city hospitals. Being culturally appropriate with communication, time constraints and attire mattered. At group discussions, aspects such as using respectful language, being tolerant of each other and remaining calm were reinforced. Additionally, listening intently and being interested and open to cultural differences were encouraged.

The first author anticipated that students might experience culture shock, which is typically understood negatively and defined as confusion when exposed to a foreign environment (Maginnis & Anderson 2017). Not understanding behavioural cues or customary norms from another ethnic group can lead to frustration as the student midwives attempt to address their own prejudices or systems of values. Culture shock can be overwhelming and inhibit learning in a new environment (Maginnis & Anderson 2017). Thus, understanding the reality of culture shock mattered. At times, students did feel unaccepted and did not know how to interact with hospital staff. In an effort to allay apprehensions, the first researcher was able to draw on her previous experience with different cultures in under-resourced areas. Consequently, steps were taken to explain to the students that the staff were indeed very interested in them, but there was a language barrier, and so the students needed to accept that communication was difficult. Additionally, the first researcher reminded the midwifery students to consider the resources that were provided to the women by the hospital. Doctors at the hospital informed us that there was little capacity to care for women, postnatally once they went home. Hence, communicating with women about the procedure of cutting an early episiotomy in second stage of labour was paramount, in order to avoid a third degree tear. Managing the care required postnatally, when a woman receives a third degree tear to her perineum would be very difficult in the community. As the clinical placement unfolded, conversations such as managing a third degree tear, emerged between midwifery students and hospital staff and mutual understanding was forged. Time was also spent talking through the way other health conditions were managed in an effort to better understand why certain practices occurred. Experiences like this challenged students' thinking.

The focus of the placement for students was to have them immersed in the birthing experiences with women. The model of midwifery care in the rural hospital was woman-focused, encompassing inclusion of family and particularly the woman's mother. Rarely was there involvement from the doctor. In contrast, in the tertiary city hospital, all the births witnessed by the students were conducted by doctors and there was less reliance on the woman's mother or family. This rural‒city dichotomy mattered because the students found reliance on medical intervention challenging. The midwifery students carried with them their paradigm of practice focused on providing care that was woman-centred and inclusive of the family.

Formal lesson times for the student midwives were timetabled into the weekly placement schedule. The students did find the limited internet connectivity an issue as it affected their learning. As part of the feedback cycle in PBL, students individualised the mechanism for how they each presented their findings to the group. In the face of limited internet capability, traditional and some innovative methods were used, such as using butcher paper, artwork diagrams, tables, action flow charts, quizzes and even role play-to convey information in a teaching forum to other students in the group.

On matters related to being away from home, the students were active on video calls (such as FaceTime) with the consequent effect that students did not report being too homesick. The lack of internet connectivity due to limited Wi-Fi bandwidth at the accommodation did evoke some minor distress among a small number of students. The first author was able to intervene, promoting respectfulness for each other's needs and encouraging book reading or conversations with each other. To counter this problem, students also purchased subscriber identity module (also known as 'SIM') cards to connect to the local phone system. One student even received a 'snail mail' letter, which actually excited the group.

Students consulted with the hospital and community representatives to ascertain details of the gift presentations. Steps were taken so that birth bundles were initially given to those women who birthed with a midwifery student present, and then any remaining bundles were left for the staff to hand out at their discretion. The money raised through fundraising was presented in a planned, formal meeting with local and hospital representatives. This formal handover was accompanied by UQ certificates and photos to record the occasion. The actual handover of money was made via international bank transfer.

Students were immersed in the care of pregnancy-related conditions, including multiple caesarean sections and interestingly, management of sickle cell anaemia. They also witnessed confronting situations such as cardiac arrest and a surgical amputation. For some students, this was the first opportunity to enter an operating theatre or emergency department. Debriefing about these situations occurred in the daily discussion time and was imperative to clarify and consolidate information. The debriefing sessions were a valuable exercise because they stabilised the group's emotions and promoted group cohesiveness. The debriefing included researching what the condition was, how the condition should be managed in the Indian setting compared to back in Australia and how the student felt immersed in the situation. A final step saw each student researching a topic around a relevant health care issue they had witnessed. This research was then presented back to the student group in an effort to improve preparedness for the next day of the placement.

Students are exposed to different health care settings to purposefully implore them to understand aspects of illness or disease across the globe and be more culturally aware of associated issues (Gower et al. 2017). Educational institutions are keen to promote international clinical placements with an intent to produce culturally sensitive future health care clinicians (Gower et al. 2017).

Findings in the literature substantiated what was experienced by this cohort of students. For instance, Lewis (2017) described care in a Vietnam location that was similar to the placement in India. Hence, it is not unusual in developing countries to have limited resources or encounter practices that differ from one's own.

As was the case in India, in the Vietnamese city hospital setting, families were not allowed in the birthing suites with the woman. Likewise, in both countries in the city hospital setting, oxytocin was used for stimulating labour and administered without a mainline or infusion pump. In India, the midwifery students witnessed women being discouraged from making any noise during labour and pushing from 8 cm dilatation instead of the readily recommended 10 cm (Pairman et al. 2019). The practice of early pushing was also noted in the literature describing the Vietnam setting (Lewis 2017).

Elsewhere, Saravanan et al. (2011) note that traditional Indian birth attendants are trained to position a woman on her back, portraying a medical 'women as object' perspective, rather than as a person who requires support and encouragement in childbirth. Alongside the specific cultural practices encountered, the first author encouraged the students to do what they had also learnt in theory and practice in Australia. This included discussing birthing in different positions with the woman, inclusive of and through the local midwife. Mostly this meant discussing side lying and back rubbing, which are recognised as instrumental as a coaching method to help women progressing through their labour (Pairman et al. 2019). The students were proactive and used opportunities to discuss with mother and staff regarding maternal aspects of care like the 'skin to skin' technique-such as the mother holding her baby after a birth (Pairman et al. 2019). The staff were receptive to this activity and interested in supporting the woman in this way, while the women were eager to hold their baby.

Recognising an in-country experience would be very much about exposure to health care differences. During the selection interview process, students were asked about what they perceived would be cultural concerns while in India. This mattered because the students who demonstrated an understanding of the cultural differences were chosen over those who could not. For example, students were asked about the appropriateness of a male student midwife caring for a labouring woman in India. This type of questioning sought to make an initial determination about how a student might act or respond to the varying circumstances they were likely to be exposed to while in India. Additionally, an awareness of one's own beliefs matters as it influences the essence of the therapeutic relationship and highlights that communication styles need to be culturally appropriate (McGee 2011).

In-country, the students generally became better listeners and took opportunities to seek clarification around practices they did not understand. On this placement, the students worked in pairs each day, which provided them with peer support and 'check-ins' with each other. This strategy, along with daily debriefs, provided a time to voice their concerns or questions and analyse their developing cultural competence.

The students' orientation to the placement was similar to other international clinical placement preparations and included workshops-which incorporated specific regional geographical and political information; advice around visa and immunisation requirements; briefings about possible encounters in the hospitals; what to wear; and behaviour and safety issues during free time (Pettys et al. 2005). In addition, on arrival in-country, further specifics were formally discussed on what to expect with tipping, greetings, the general cost of food items, obtaining maps of the local areas and availability of food and retail outlets.

In the preparation period leading up to departure and while in India, the first author shared her experiences and lessons learnt from 25 years of clinical practice. Across time, this included direct clinical instruction and prescriptions for professional and social behaviour. Through this guidance, students were able to make good choices, enact good actions and demonstrate respectful behaviour to local staff and the broader community. Fostering student awareness of cultural differences within the health care system and in daily activities was imperative for the first author (as the supervisor) to ensure the students were respectful. This is an intrinsic quality of nurses and midwives evidenced by kindness, concern and interest in the people they are looking after (Tuckett 2014).

Overall, the international placement was an enriching and stimulating experience for the midwifery students. Even with unpredictable internet connectivity, continuing with PBL lessons in an informal setting was well received by the students. Students remained engaged with the class content and utilised local textbooks. The students presented their critical PBL feedback using innovative methods that did not necessarily require e-based technology. Especially important, and of great benefit, was the time spent by students researching topics of interest, accompanied by reflection and debriefings.

On the group's return to Australia, the first author had further opportunity to think about the planning involved and the experiences that occurred while on the clinical placement. On hindsight, possibly over-monitoring and over-supervision of students may have been stifling and restrictive for them. At the same time, being acutely aware of and monitoring dress restrictions and the display of culturally-appropriate gestures and language was taxing on the first author. Nevertheless, the students exhibited a great deal of maturity. They displayed a great capacity to cope. Despite not knowing hospital routines and only conversing in English with hospital staff who were culturally and linguistically diverse, students managed to care for a large number of patients. Despite the short four-week duration, the professional and personal growth witnessed in the students will be valuable in preparing them for future challenges in their midwifery career and also general life experiences.

In a final debrief workshop at the home university, the students were given an opportunity to discuss and reflect on what they had observed and experienced. The period of time (six weeks) between returning and the workshop was useful. Students spoke of being challenged by witnessing the birthing practices in the tertiary hospital. They considered the rural hospital much more woman-centred and care-focused. Time had not changed these feelings. They did express a gratitude to the hospitals for accommodating the placement and remembered the kind hospitality shown to them by the communities.

Practical feedback and reflective thoughts from the students included such things as how much money to take to India and how much money to tip a 'tuk tuk' (a three-wheeled commercial vehicle) driver. Also aspects of how good will the internet be, where are the local food stores and where are the best local sites to visit. Since this was the first placement of its kind for School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at UQ, practical 'daily-living' information was unavailable for this group prior to departure. However, their travel information and synopses of experiences have been compiled into a travel guide for the benefit of future student groups to India. Funding has been received for a further placement.

This paper demonstrates the use of the GRC to describe the experiences and lessons learnt by the first author when mentoring midwifery students on an international placement to India (Gibbs 1988). Specifically highlighted is the methodical progression of recruitment of the students and an application of the GRC to systematically recollect what happened while the group was away and how issues were managed or overcome. The larger goal of this paper was to offer some direction for lecturers and undergraduate midwifery students in their own reflective practice.

There were the expected issues such as language barriers, cultural differences in food and dress and the experience of observing confronting health conditions (Tuckett & Crompton 2014). Two clinical realities were at best, underestimated. These were (i) anticipating broader hospital systems whereby large numbers of patients were cared for while relying on very limited resources, and (ii) the initial reluctance of local hospital staff to communicate with the midwifery students.

Attending this clinical placement provided students with the opportunity to consider international experiences when they returned to their local hospitals. The student reflection recorded here provides new insights and reinforces existing knowledge into international clinical placements, especially those involving midwifery students. Since it is encouraged to benchmark experiences against existing research (that documents like placements), the results of this study offer a model that can be applied to future international clinical placements. While the reflections recorded in this study provide practical advice for lecturers, it importantly also provides students with a glimpse into what to expect when preparing for and embarking on an international clinical encounter.

We would like to thank the hospital staff and the students who participated in this international placement. Reflections from this placement will assist in future international placements.

There is no conflict of interest in the writing of this paper.

No funding was used in the writing of this paper.

Australian Government 2018, New Colombo Plan, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra.

Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency 2019, Applying for registration, viewed 09 October 2020, https://www.ahpra.gov.au/Registration/Registration-Process.asp

Da Silva, AB, de Araujo Bispo, AC, Rodrguez, DG & Vasquez FIF 2018, 'Problem-based learning: a proposal for structuring PBL and its implications for learning among students in an undergraduate management degree program', Revista de Gestao, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 160‒177.

Gibbs G 1988, Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods, Oxford Polytechnic, Oxford.

Gower, S, Duggan, R, Dantas, JAR & Boldy, D 2017, 'Something has shifted: nursing students' global perspective following international clinical placements', Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 73, no. 10, pp. 2395‒2406.

Lincoln, B 2016, Reflections from common ground: cultural awareness in healthcare, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Scotts Valley, California.

Koshy, K, Limb, C, Gundogen, B, Whitehurst, K & Jafree, D 2017, 'Reflective practice in health care and how to reflect effectively', International Journal of Surgery Oncology, 2:e20.

Lewis, E 2017, 'Supporting student practice: reflections on the first University of Canberra international midwifery student placement in Vinh Long, Vietnam', Australian Midwifery News, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 54‒55, viewed 09 October 2020 https://search.informit.com.au/fullText;dn=929429683090210;res=IELHEA .

Maginnis, C & Anderson, J 2017, 'A discussion of nursing students' experiences of culture shock during an international clinical placement and the clinical facilitators' role', Contemporary Nurse, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 348‒354.

MaRS Discovery District 2019, Designing and scoring a job interview with an interview assessment template, viewed 8 September 2019, https://learn.marsdd.com/article/designing-and-scoring-a-job-interview-with-an-interview-assessment-template/.

McGee, P 2011, 'Developing cultural competence', Independent Nurse , vol. 2011, no. 6, viewed 12 December 2018, https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/10.12968/indn.2011.6.6.84291

Narayan, R, Rodriguez, C, Araujo, J, Shaqlaih, A & Moss, G 2013, 'Constructivism-constructivist learning theory', in BJ Irby, G Brown, R Lara-Alecio & S Jackson (eds.), The handbook of educational theories. IAP Information Age Publishing, North Carolina, pp. 169‒184.

Nilson, C 2011, 'International student nurse clinical placement: a supervisor's perspective', Australian Nursing Journal, vol. 19, no. 3, p. 35.

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2016, Guidelines: continuing professional development, Canberra, ACT 2600: Australian Health Practitioner Agency (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency).

Pairman, S, Tracy, K, Dahlen, H & Dixon, L 2019, Midwifery: preparation for practice, Elsevier, New South Wales.

Pettys, GL, Panos, PT, Cox, SE & Oosthuysen, K 2005, 'Four models of international field placement', International Social Work, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 277‒288.

Regulators unite to support reflective practice across health and care 2019, BDJ In Practice, vol. 32, no. 7, viewed 09 October 2020, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41404-019-0109-1.

Rowan, CJ, McCourt, C & Beake, S 2008, 'Problem based learning in midwifery-the students' perspective', Nurse Education Today, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 93‒99.

Saravanan, S, Turrell, G, Johnson, H, Fraser, J & Patterson, C 2011, 'Traditional birth attendant training and local birthing practices in India', Evaluation and Program Planning, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 254‒265.

Tuckett, A & Crompton, P 2014, 'Qualitative understanding of an international learning experience: what Australian undergraduate nurses and midwives said about a Cambodia placement?' International Journal of Nursing Practice, vol. 20, no. 2, pp.135‒141.

Wain, A 2017, 'Learning through reflection', British Journal of Midwifery, vol. 25, no. 10, pp. 662‒666.

Watkins, A 2018, Reflective practice as a tool for growth, viewed 10 May 2019, https://www.ausmed.com/cpd/articles/reflective-practice .

Wilding, M 2008, 'Reflective practice: a learning tool for student nurses', British Journal of Nursing, vol. 17, no. 11, pp. 720‒724.