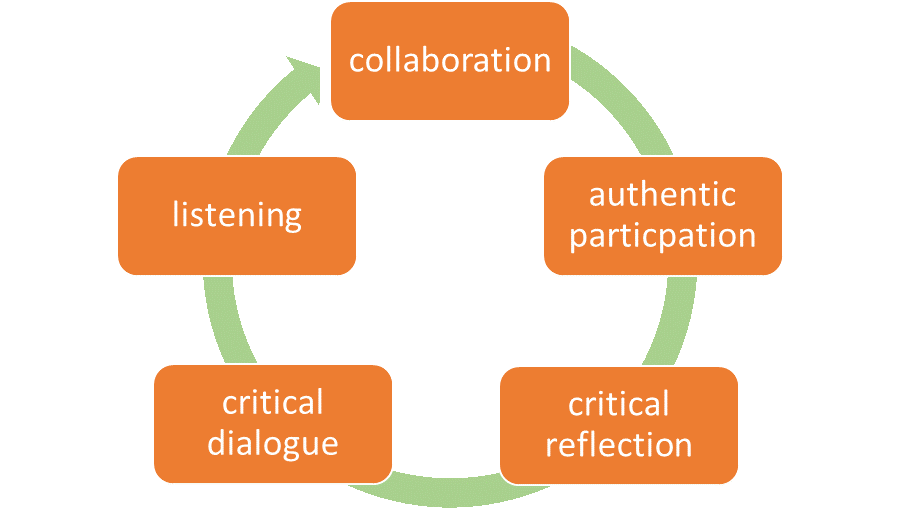

This paper aims to share a program that took a whole-hospital approach in considering the wellbeing of staff at a time of recovery following the 2019–2020 bushfires. The SEED Program enlisted a person-centred participatory methodology that was embedded within a transformational learning approach. This methodology included collaboration, authentic participation, critical reflection, critical dialogue and listening where the staff voice was the driving factor in the development of strategies for recovery. The SEED Program resulted in the development of five initiatives that included four strategies and a celebration event where staff celebrated their New Year’s Eve in February 2020. The four strategies included the establishment of a quiet room, coffee buddies, Wellness Warriors and 24/7 Wellness. The outcomes from the SEED Program resulted in the development of a more person-centred culture and transformation of staff perspectives in how they understood their role in their learning and learning of others in recovery and support at a time of crisis. The key learnings were the effect of authentic collaboration, the benefit from enabling authentic leadership at all levels within a hospital, and the power of a staff connection to the ‘CORE’ values of the hospital and Local Health District. In conclusion, the staff involved hold the hope that others may benefit from their experience of transformational learning in creating more person-centred workplace cultures while supporting each other to move forward during a crisis. The limitation of the SEED Program was that it was a bespoke practice innovation designed in the moment, responding to an identified need for the staff following a crisis in the local community rather than a formal research approach to meeting the needs of this group of staff.

1 University of Wollongong

2 Queen Margaret University

3 Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District

Focusing on the wellbeing of staff has become a priority for workplaces recently. During the recent bushfires in NSW (2019–2020), a collaborative project to address the wellbeing of staff was undertaken in a rural hospital on the South Coast. The project outlined within this paper involved the co-design and implementation of the SEED Program. This paper shares the collective learnings of the hospital executive and staff who came together as a community to support and nurture each other through a community crisis. The project aimed to support and enable the staff in a small rural hospital to create learning opportunities, both about themselves and others, from their shared experience during the bushfires.

The project was initiated by the Local Health District (LHD) Chief Executive (CE), supported by the LHD Executive and led by the Director of Nursing & Midwifery Services. The town where the hospital is situated on the South Coast of NSW and the surrounding areas were unprecedently devastated by the 2019–2020 bushfire season. Members of the local community predominantly staff small rural hospitals. Therefore, the project was developed with an embedded assumption that there may be a broader effect of support felt across the local community by supporting the hospital staff.

Wellness programs for healthcare staff have been evaluated in limited peer-reviewed research studies, emphasising health professionals. Archibald et al. (2011) explores online resources for healthcare workers and finds the advantages of online tools in programs that anonymise the staff. Gengoux and Roberts (2018) focus on physician wellbeing and self-care from both individual and system approach. They advocate that organisations have a responsibility to be proactive in initiating wellness programs (Gengoux & Roberts 2018). The SEED Program considered staff from all aspects of the healthcare organisation. There is currently no literature evidence that takes this holistic and whole-hospital approach to staff wellbeing.

There is limited evidence regarding the wellness programs for healthcare professionals for post-disaster recovery and support for healthcare workers. O’Halon and Budosan (2019) argue that resources are required to improve communities’ mental health in the immediate response and over a long period of time to assist people with recovery. For health professionals, the current focus within the literature aims to prepare staff for the next disaster (Rokkas, Cornell & Steenkamp 2014). Specifically, related to bushfires recovery, research after the Black Friday bushfires found that the nurses’ role expanded to include care coordination, problem-solving and psychosocial care for the community (Ranse & Lenson 2012). Support for the nurses themselves or other healthcare staff was not discussed. There is a pause in the current literature in addressing wellness in healthcare staff following a crisis.

The theoretical lens that influenced the development and implementation of the SEED Program was a combination of transformational learning and person-centredness. McCormack and McCance (2017) would argue that transformation is inherent within the concept of person-centredness. Transformational learning can be viewed as an opportunity to create new knowledge and new ways of experiencing the world (Mezirow 2009). It recognises that disorienting dilemmas are the foundation for transformative learning. Respecting personhood is a fundamental concept within person-centredness. Personhood is defined by McCormack and McCance (2017, p. 60) as ‘enabling others to live their life plan without placing our values and beliefs upon them.’ Person and personhood are fundamental elements in working in creating person-centred cultures. For this project, transformational learning and person-centredness guided the collaborative and participatory nature in which staff experienced the SEED Program.

The SEED Program was conducted using a person-centred participatory approach. In line with person-centred research principles, authentic participation and transformation is the desired outcome (McCormack & McCance 2017). The participants remained in control of the level to which they engaged and were free at any time to stop participation (Hahtela et al. 2017). Collaborative participation was a principle that also fed through the development, implementation and evaluation of the SEED Program. Finally, the principle of criticality was significant in the person-centred participatory approach to applying the methodology. Critical reflection and critical dialogue were utilised in the methods to enable the staff to consider their current understanding or worldview with the hope that this would enable movement and transformation in their understanding through their engagement with the elements within the SEED Program (Mezirow 1990). Listening to others and to self was an element that emerged as being important. Having patience for people to participate in a way that enabled their personhood stood out as aspects of the methodology that emerged naturally. Below represents the methodological approach taken.

Based on suggestions from 42 staff through their active participation in focus groups and individual consultations, the SEED Program was developed. It encompassed four initiatives (the quiet room, coffee buddies, Wellness Warriors and 24/7 Wellness); see Figure 2. The notes from each of the focus groups were themed by the project lead in collaboration with a sample of the participants. Following this, all participants had an opportunity to review and comment on the themes. The themes were then used to create the four initiatives (Hahtela et al. 2017). It was hoped that by staff influencing the development of the initiatives within the SEED Program, they would engage with and learn from the disorientating dilemmas they had experienced (Mezirow 1990).

In the implementation phase of the project, one initiative was implemented each week over a four-week period. An additional 5th initiative was a celebration that was held following suggestions from the staff. In the focus groups and interviews, many staff expressed concerns that they were not able to end 2019 due to the timing of the bushfires. To address this, the hospital executive coordinated a party that was attended by many staff and their families entitled ‘SEE YA 2019’.

The first initiative launched was the ‘Quiet Room’, which was created to provide staff with a safe space to take a moment for some quiet reflection. The creation of the quiet room was done collaboratively and creatively, with staff and community members donating furniture, art and aromatherapy oils to fill the space. The room is located at the end of the ward, promoting easy accessibility for staff during their busy work schedules. A significant art feature of the room is a hand-crafted wooden tree placed on the wall, created and donated by a staff member, resembling the hospital’s growth following the bushfires. An important outcome of the quiet room is that staff were given an option to write a personal reflection. Reflections are written on a sticky note shaped like an apple on the tree. There are currently more than 250 reflections on the tree, and the tree continues to grow.

The second initiative, titled ‘Coffee Buddies’, was the use of three local cafes. They joined in the project to form a partnership and provide a safe space for staff to informally interact, have a weekly coffee, and check in on each other’s wellbeing. A deliberate attempt was made to match each staff member with a person they would not usually work closely with and send them for a free coffee to connect on a human level. This has resulted in learning from each other through vulnerability (Brown 2010). Staff have shared that they have connected with people that they have never spoken to before. Their learning has been in a new understanding that regardless of your role in the hospital, we are all people, and we share the same challenges. Three months post the inauguration of the coffee buddies, and there has been an evident culture change at the grassroots level, with 210 coffees consumed.

The third initiative implemented was ‘Wellness Warriors’. Eighteen staff across all areas of the hospital attended a two-day peer support training in the ‘Art of Companioning’. This program was developed and delivered in collaboration with the local University partner. Underpinned by a strengths-based approach of peer support, the focus of the training was on being a better listener, listening to understand and hold space for others. Learning shared by participants included an understanding that leadership is a shared responsibility across all staff. Staff who participated found that developing skills in holding space for others was an empowering and learning experience for both the person who spoke and the person who was listening.

The final initiative implemented was the ‘24/7 Wellness’ sessions. These sessions were held twice a week, run by staff members themselves and open to all staff to attend. The sessions provide a safe space to discuss a variety of topics around staff wellness and self-care. The program links to a recent successful ‘Imagine Program’ that was run across the LHD. A total of 305 staff attendances at the wellness sessions. The success of this program can be observed in the attendance, with many staff attending on days they were not rostered to work.

In conclusion, the SEED Program has positively affected the hospital culture, with several key learnings for the leadership team and staff being evident. Transformational learning enabled the staff to reconsider their worldview and be open and emotionally ready to take steps forward (Howie & Bagnall 2013; Mezirow 2009). It is hoped that some of these learnings may be relevant for other hospitals and health services in times of community crisis.

A significant learning has been the realisation of the effect of authentic participation among staff at all levels within the hospital. Authentic collaboration and participation were evident from the development through to the implementation of the SEED Program. Staff were actively involved in determining their needs and designing a program that would suit their community. Gengoux and Roberts (2018) advocate that organisations have a responsibility to initiate wellbeing programs; however, in line with person-centred perspectives, the provision of these programs needs to be undertaken in a collaborative and participatory way where staff feel they are seen and heard (McCormack & McCance 2017). Authenticity is defined by Brown (2010, p. 50) as a ‘daily practice of letting go of who we think we’re supposed to be and embracing who we are’. This enabled the cultivation of a shared understanding that everyone was doing the best they could to participate, creating a sense of acceptance among all the staff (Brown 2019). An example of respecting the personhood of others in them determining their own participation involved a Wardsman who participated in all the elements of the program. He reported that he had never seen himself as a leader; however, by becoming a Wellness Warrior, he could see that his small part in connecting with others was making a difference.

The next key learning was the effect that authentic leadership had on creating a sense of shared leadership in the hospital. Authentic leadership focuses on transparent and ethical leader behaviour and encourages open sharing of the information needed to make decisions while accepting followers’ inputs’ (Avolio, Weber & Walumbwa 2009). Leadership within the SEED Program was initially at an executive level, recognising the need in a community devastated by the bushfires and the provision of resources to support the community. This flowed to recognising the need to develop leaders at all levels within the hospital community and support staff on their leadership journey. Ranse and Lenson (2012) identified a need to provide a suite of support at the time of the disaster. This was realised in the SEED Program with funding being provided for additional experienced staff, including a project lead, and to enable then initiatives to be implemented.

The final key learning connects authenticity with living the organisation values. This aligns closely with the pre-requisites of the Person-centred Practice Framework ‘knowing self’ (McCormack and McCance 2017). The ‘CORE’ Values of NSW Health drove the approach to enable the empowerment of this hospital community to move towards recovery. The significance of living their values was at the forefront of the development and implementation of each of the initiatives. The memories created through this project remain evident in the hospital with the continuation of the quiet room and 24/7 wellness sessions, coffee buddies continuing to meet, and the effect the Wellness Warriors continue to have.

The limitations of this project include the responsive and organic nature of the SEED Program. This is a strength in that it has allowed the program to be responsive to the need and the crisis. However, it is also a limitation in that the learning in the development and implementation of the program was not formally evaluated or approved through an ethics committee. It was deemed that ethical approval was not required as this was an in the moment practice innovation. Further research is required to formally evaluate the SEED Program’s effect on the experiences and learnings that staff have gained.

We would like to acknowledge that wonderful staff at Milton Ulladulla Hospital who have shown amazing resilience in their recovery following the bushfires. We would also like to acknowledge the Chief Executive and senior leadership team of the Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District for their leadership and support within the SEED Program.

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

The authors did not receive any funding to undertake the SEED Program.

Brown, B 2010, The gifts of imperfection, Hazelden Publishing,Minnesota, USA.

Brown, B 2019, Dare to lead, Ebury Publishing, London, UK.

McCormack, B & Mccormack, T 2017, Person-centred practice in nursing and health care: Theory and practice, 2nd ed, Wiley Blackwell, West Sussex, UK.

Mezirow, J 2009, ‘Transformative learning theory’, in J Mezirow & E W Taylor (eds.) Transformative Learning in Practise: Insights from Community, Jossey Bass, California, USA.

Polit, D & Beck, C 2012, Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, 9th ed, Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.