Health Education in Practice: Journal of Research for Professional Learning

Vol. 7 | No. 1 | 2024

Education-in-practice article (single blind peer-review)

Copyright is held by the authors with the first publication rights granted to the journal. Conditions of sharing are defined by the Creative Commons License Attribution-ShareAlike-NonCommercial 4.0 International

Citation: Delaney, AM, Duffield, JA, Iten, R, Heywood, M, McLarty, AM & Bowers, AP 2024, ‘An education model for paediatric palliative care’, Health Education in Practice: Journal of Research for Professional Learning, vol. 7, no. 1 https://doi.org/10.33966/hepj.7.1.17855

An education model for paediatric palliative care

Angela M Delaney  1,6, Julie A Duffield

1,6, Julie A Duffield  2, Rebecca Iten

2, Rebecca Iten  3, Melissa G Heywood

3, Melissa G Heywood  4, Alison M McLarty

4, Alison M McLarty  1,6, Alison P Bowers

1,6, Alison P Bowers 5,6

5,6

Abstract

Introduction:

Meeting the palliative care needs of children and their families is

complex and challenging. For countries such as Australia, whose

relatively small paediatric palliative care population is dispersed

across a very large geographical area, one challenge is maintaining a

skilled workforce in regional, rural, and remote areas, where, when

compared to major cities, there are fewer resources, and the workforce

is often transient.

Methods:

The Quality of Care Collaborative Australia (QuoCCA) Pop-up Model of

Education was used to provide palliative care education to health

professionals across three geographical locations and facilities, to

facilitate a 2,500-km transfer of a child with complex palliative care

needs from a tertiary hospital to the remote family home on

Country.

Results:

Each Pop-Up provided effective education to facilitate the successful

transfer of the child to the next hospital location. Over 18 months,

three Pop-Ups occurred. Relational learning and real-time problem

solving enabled health professionals to build confidence and capacity

to successfully transfer the child from the regional hospital to the

remote family home.

Implications:

The QuoCCA Education Pop-up Model is a feasible method to deliver

timely access to speciality education. The model can be successfully

applied in multiple settings.

Keywords:

paediatric, palliative care, integrated health care delivery, learning,

rural, education models.

1 Paediatric Palliative Care Service, Children's Health

Queensland Hospital and Health Service, Brisbane, Australia

2 Paediatric Palliative Care Service, Women's and Children's

Health Network, Adelaide, Australia

3 Paediatric Palliative Care Service, Perth Children's Hospital,

Perth, Australia

4 Victorian Paediatric Palliative Care Program, Royal Children's

Hospital, Melbourne, Australia

5 Cancer and Palliative Care Outcomes Centre, Centre for

Healthcare Transformation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane,

Australia

6 Centre for Children's Health Research, Queensland University

of Technology, South Brisbane, Australia

Corresponding author: Angela M Delaney, Queensland

Children's Hospital, 501 Stanley Street, South Brisbane, Queensland, 4101,

Australia,

[email protected]

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, specialist paediatric palliative care (SPPC)

services have grown globally (Ekberg, Bowers & Bradford 2021). As the

need and demand for SPPC continues to grow faster than the specialist

workforce, it is imperative that alternative models of SPPC education are

explored to ensure that high quality, well-coordinated family-centred care

is delivered in the right place at the right time (Mherekumombe 2018).

Compared to the adult population, the paediatric palliative care population

is relatively small and often geographically dispersed. The combination of

the complexity of the child's condition and intricacies of health systems

makes delivery of paediatric palliative care challenging (Bowers et al.

2020). Delivery of such care in areas where there are less resources and

fewer service providers can add further complexity (Queensland Health

2019).In Australia, the distance and diverse terrain between

major cities, where SPPC services are based, and regional, rural and remote

areas where families live is an additional challenge to timely palliative

care (Dassah et al. 2018).Children receiving palliative care

present with varying considerations including rarity of diagnoses,

developmental considerations, complex symptom management and the

psychosocial implications of family-centred care (Bowers et al. 2020).

In 2015, the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia (QuoCCA) project, a

nationally funded collaboration of interdisciplinary services, was

established to deliver paediatric palliative care education to health

professionals across Australia who may care for children with palliative

and end-of-life care needs. The aim of this national collaborative is to

'improve the quality of palliative care provided to children in close

proximity to their home, throughout Australia through innovative

education.' (CareSearch & QuoCCA 2018). The Commonwealth Department of

Health and Aged Care National Palliative Care Projects has continued to

fund the QuoCCA project through to June 2026.

METHOD

The QuoCCA project was conducted in collaboration with the five state-wide

SPPC services. The aim was to ensure education was delivered to health

professionals caring for children with life-limiting conditions across

Australia and the families of the children. Ethical approval was obtained

from the Children's Health Human Research Ethics Committee. Informed

consent was obtained verbally and in written form from the participant in

this report. This paper uses Jo's (pseudonym) 18-month journey to describe

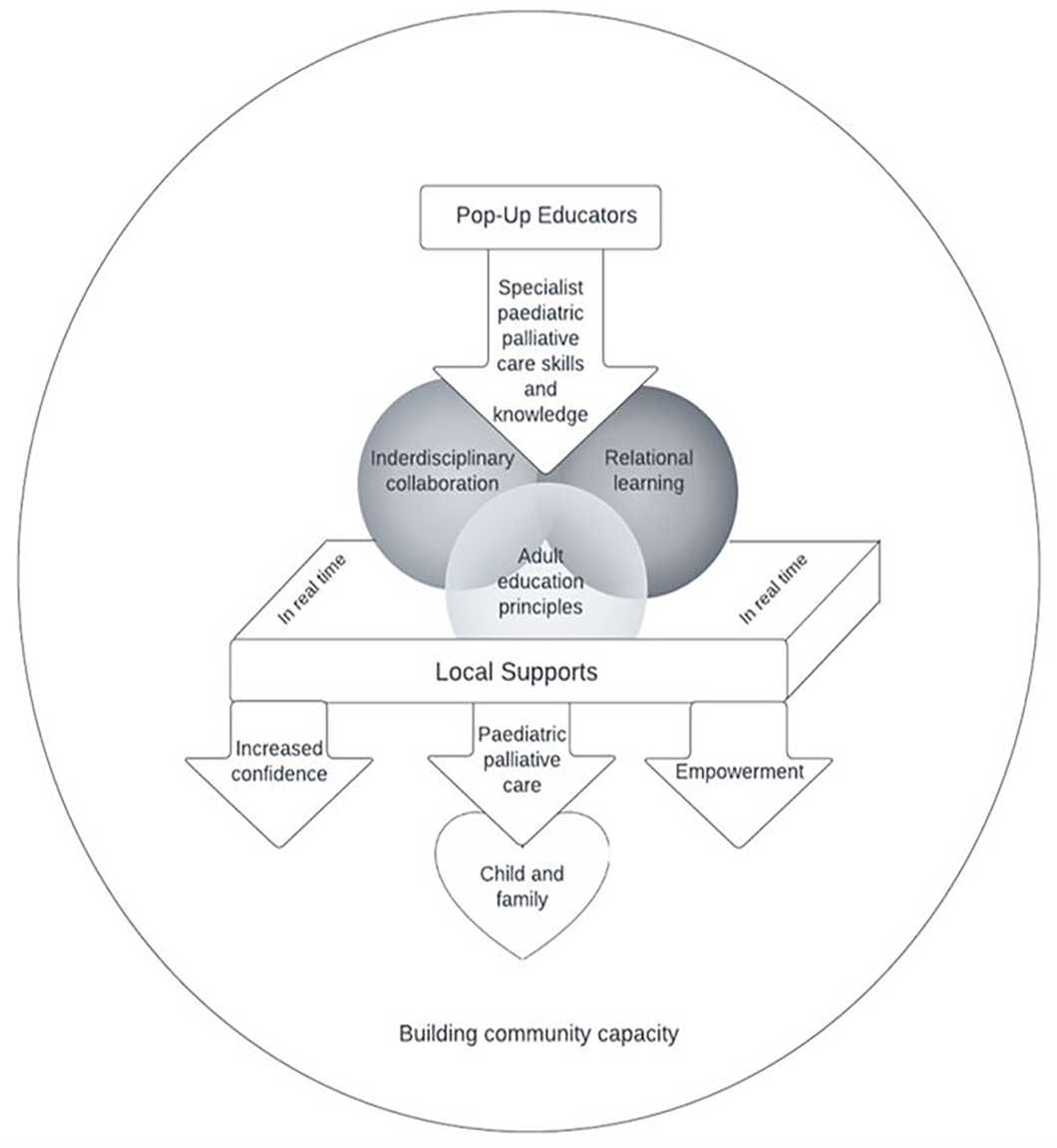

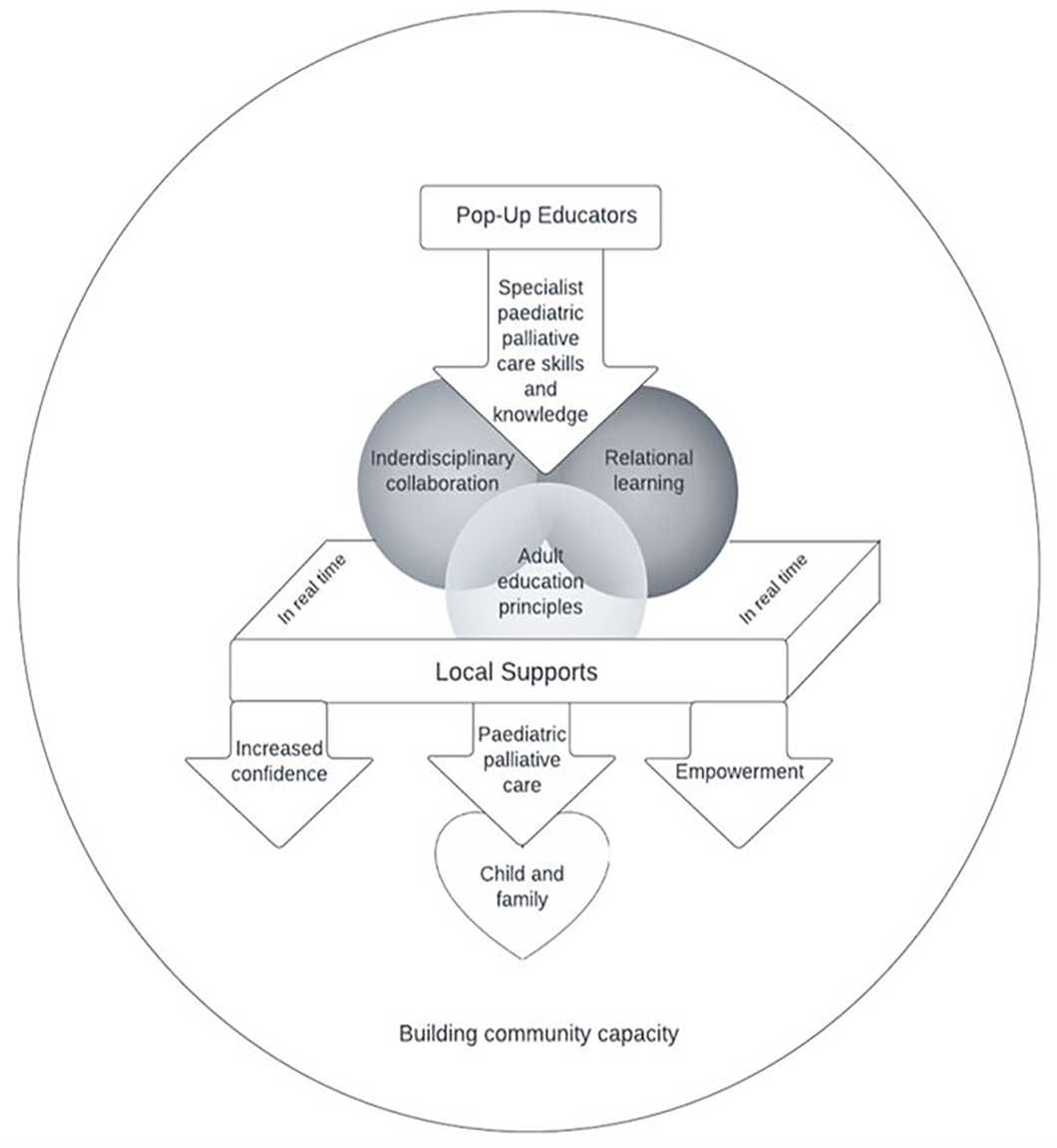

the QuoCCA Education Pop-Up Model for Paediatric Palliative Care (QE-PMOC)

(Figure 1) in practice. The QE-POMC aligns with central tenets of the

public health approach to palliative care, as it encourages collaboration

between acute and community services, supports the creation of supportive

environments and helps strengthen community action (Rosenberg, Mills &

Rumbold 2016).

Figure 1. QE-PMOC. This model is designed to deliver paediatric palliative

care education that facilitates collaboration and capacity building.

The Pop-Up Model

A Pop-Up is described as 'a specific intervention over and above care

that is provided to a child and family, with identified goals,

objectives and interventions leading towards improving the confidence

of local health care providers to deliver paediatric palliative care'

(Mherekumombe et al. 2016; Mherekumombe 2018). The QuoCCA project has

developed the QE-PMOC with other key enablers using the principles of

Pop-Up education (Table 1) to deliver education to individuals involved

in the care of the child and their family. These key enablers are

central to the development of the education while allowing for

flexibility of delivery.

Jo's case is used to illustrate how the QE-PMOC is implemented to deliver

effective palliative care education, resulting in the collaboration and

capacity building of health professionals.

Table 1: Key enablers for Pop-Up education

|

Key Enablers

|

Definition

|

|

Adult learning principles

|

Enhance the transfer of knowledge and understanding for

health professionals providing patient care.

1. Need to know

2. Self-concept

3. Prior experience

4. Readiness

5. Learning orientation

6. Motivation to learn

|

|

Relational learning

|

Learning via vicarious lived experience enhances a deeper

understanding of the child and family's lived experience.

|

|

Real time

|

At the time of care delivery, tailoring topics to

learners' needs in relation to the specific care issues of

the patient and family.

|

|

Local champion

|

Local champions are the point of contact health

professionals who take responsibility for the facilitation

and coordination of care, and education sessions to other

health professionals, conveying the family's goals of

care.

|

(Browning & Solomon 2006; Slater, Osborne & Herbert 2021; Adult

Learning Australia 2024)

THE CASE OF JO

Jo, an Aboriginal Australian, was born prematurely. Jo had multiple health

complications and co-morbidities that would shorten life expectancy. Jo's

family live in a remote community over 2,500 km from the tertiary health

service where Jo was an admitted patient. It was of cultural importance

that Jo and family lived on

Country[1]. Although Jo's life expectancy

remained shortened, several months later, Jo's condition was stable enough

to consider a transfer to a hospital on Country closer to the family's

community.

RESULTS

Due to the vast distance and remote terrain between the tertiary hospital

and Jo's community, Jo's transfer home required three Pop-Up education

sessions over a period of two years. The first transfer was from the

tertiary hospital to a small remote hospital >1,000 km from the family

home.

The first Pop-Up

The SPPC Nurse Educator (NE) and the Regional Adult Palliative Care Service

(RAPCS) visited the child and family in the remote hospital within a month

of the first transfer. The first Pop-Up occurred during this initial visit.

Education Topics

Many staff in rural or remote hospitals have never cared for a child with

palliative care needs; therefore, it is important that the professionals

involved identify the topics relevant to their learning needs in caring for

the patient and family. The health professionals caring for Jo experienced

moral and ethical challenges, and identified general care, complex symptom

management and how to navigate moral and ethical challenges when delivering

best-practice palliative care as relevant topics.

The Local Champion

Identifying a 'local champion' is an important element of facilitating a

Pop-Up. The SPPC NE engaged the RAPCS Aboriginal Health Worker (AHW), who

already had an established relationship with the family, and understood

their need for culturally safe care, to help coordinate and facilitate

group and one-to-one education sessions at the rural hospital.

Relational Learning In Real Time

The collaboration between the AHW and the SPPC NE facilitated the delivery

of education sessions that met the needs of the health professionals and

the culturally safe holistic care of the family in real time. This enabled

health professionals and the family to be supported as they navigated

decision-making and care interventions.

The second and third Pop-Up

In Jo's case there were two more Pop-Ups to facilitate subsequent

transfers. Local champions were identified from each hospital and worked in

partnership with each other, other health professionals, and the community

services that provided care to Jo and Jo's family.

For the second and third Pop-Up, topics and support provided by the SPPC NE

to health professionals were directed by each participating group, proving

similar to the learning needs of the previous group. At each transfer point

the SPPC NE provided Pop-Up face-to-face education, while the

interdisciplinary specialist paediatric palliative care service provided

support and guidance via telephone, email, and telehealth throughout all

stages of Jo's journey back to Country. During a Pop-Up visit, the SPPC NE

will often visit the patient in the family home. In Jo's case the SPPC NE

visited the family home and provided education to the support workers. The

number of stakeholders and interagency collaborations grew with each

transfer, building the capacity of clinicians across the geographical

expanse.

Throughout Jo's 18-month journey, the SPPC NE was supported, via the QuoCCA

project, to facilitate three in-person Pop-Ups which delivered education

and support to over 60 health professionals, from three acute service

providers (hospitals) and three community health services. Table 2

illustrates specific information related to each of the Pop-Up education

sessions.

Table 2: QE-PMOC Education Dataz

|

|

Pop-Up 1

|

Pop-Up 2

|

Pop-Up 3

|

|

Timeline

|

Oct 2018 & Feb 2019

|

June 2019 & Oct 2019

|

Nov 2020

|

|

Jo's age

|

4-6 months

|

12-14 months

|

2.5 years

|

|

Location

|

Hospital & adult palliative care service

|

Hospital

|

Health centre & family home

|

|

Facilitators

|

SPPC NE & clinical nurse consultant

|

SPPC NE

|

SPPC NE & medical fellow

|

|

No. of sessions

|

3

|

4

|

3

|

|

Mode of delivery

|

Face-to-face

|

One video conference & three face-to-face

|

Face-to-face

|

|

Total Pop-Up hours

|

6.25

|

6

|

6.5

|

|

Family session hours

|

3

|

3

|

1.5

|

|

Professionals:

Medical

Nursing

Allied Health

Support worker

Other

|

3

12

11

-

13

|

3

15

9

-

8

.

|

3

3

0

6

-

|

|

Total participants

|

36

|

35

|

12

|

Evaluation of Pop-Up education at the time included open-ended responses

from educators.

Across the three Pop-Ups, the NE reported consistent themes and suggested

successful outcomes which included increased inter-professional

collaboration, improved confidence and capacity building of local

professionals, and families trusting local teams following the tertiary

team working collaboratively with local services.

"Building this relationship has been vital. We were able support the team

in their decision making and symptom management of the patient." Nurse

educator (2019).

DISCUSSION

Through in-time professional education, interprofessional collaboration and

acknowledgment of the expertise of the family, the QE-PMOC successfully

built the capability, skills, knowledge and confidence of an

inter-professional care network, and increased the capacity of the local

community (Slater et al. 2018).

As demonstrated by Jo's case, the success of the QE-PMOC is reliant on

effective education via methods appropriate to the situation and learners'

needs (Browning & Solomon 2006; Curran & Sharpe 2007). The Pop-Up

education delivered at the time of care provision promoted in-time

interprofessional collaboration, and enabled questions to be addressed and

challenges to be overcome as they occurred.

Strengths

QE-PMOC education is learner-driven, with the child and family at the

centre, resulting in the right care in the right place at the right time

(Palliative Care Australia 2018). Furthermore, the QE-PMOC can help overcome

the challenge of location by taking specialist skills, knowledge, resources

and support from the tertiary centre to the family's local service

providers and community. The QE-PMOC supports the real-time sharing of

evidence-based best-practice paediatric palliative care in the family and

patient's choice of location and at the time of need, which mitigates local

health costs of travel for professional development.

Challenges and questions can be addressed in real time, enabling

professionals to confidently provide coordinated care (Mherekumombe 2018;

Slater et al. 2018). This facilitates effective communication between local

professionals and family members. Effective communication helps

professionals to build trust with families, and helps families build

confidence in the professional's ability to provide effective care, where

the family's knowledge and experience are valued and decision making is

shared (Stein et al. 2019).

In the experience of QuoCCA educators, the local champion is a role based

on the local team's understanding and value of an individual's experience,

skills, and any existing rapport with the family. The local champion is the

key link between the SPPC NE and local health professionals and has a key

role in advocating the views and wishes of the family and in coordinating

care (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). Drawing on a

strengths-based approach (Miller 1990), the QE-PMOC facilitates reframing

what individuals feel they do not know and cannot provide, to what they do

know and can provide. Reflections of QuoCCA educators suggest that once a

QE-PMOC has been provided, local health care professionals delivering care

will confidently seek to contact the SPPC service, for reassurance,

guidance, and knowledge-sharing. This is supported by Sansone, Ekberg and

Danby (2022), who report that an SPPC provided reassurance to individuals

who called a SPPC help-line.

The model can be successfully applied in multiple settings, including in

areas with limited resources or service infrastructure. The model has the

potential to be used in specialities other than paediatric palliative care.

Limitations

Further research is needed to explore the impact of the QE-PMOC on health

professionals receiving education and on the families at the centre of the

intervention. The preparation time leading into a Pop-Up education event,

including topic preparation and coordination, has not been documented.

However, as activities associated with Pop-Up education are multi-layered

and cannot be viewed in isolation, quantifying the effects and impact of a

Pop-Up may be challenging. Despite these challenges, work is currently

underway to quantify such impacts and effects.

CONCLUSION

The QE-PMOC ensured that all professionals, services, and community members

received the education and support needed to plan and transition Jo's care

back to the family home and community. Australian SPPC educators consider

the QE-PMOC as the gold standard for improving equitable, accessible, and

quality paediatric palliative care. The QE-PMOC is a feasible method of

delivery of timely speciality education that meets the learning needs of

health professionals and the culturally safe holistic palliative care needs

of children and their families.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the family who agreed for this case

to be shared, and pay respects to their Elders, lores, customs and creation

spirits. We acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands where the

family live and where the Pop-Ups occurred. We recognise that these lands

have always been places of teaching, learning and research. We acknowledge

the important role Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people play within

our communities.

We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Ashka Jolly, QuoCCA

NE for the Australian Capital Territory, and Sarah Baggio, Allied Health

Educator, and the contributions of the rest of the National QuoCCA project

team.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding

No conflicts to declare. The QuoCCA project is funded by the Commonwealth

Department of Health and Aged Care through the National Palliative Care

Projects.

Ethics

This project received multi-centre ethics from the Children's Health

Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee reference HREC/16/QRCH/55. Both

verbal and written parental consent was obtained, as advised by HREC for

the use of this case.

Contributorship Statement

AD, JD and RI drafted the initial manuscript.

AB, AM, MH, AD, JD and RI made substantial contributions to interpretation

of the work, developed the model of care figure, and reviewed and

critically revised drafts of the manuscript for important intellectual

content. AD, JD, RI, MH, AM, and AB approved the final version for

publication.

REFERENCES

Adult Learning Australia 2024, The principles of adult learning,

viewed March 2024,

https://ala.asn.au/adult-learning/the-principles-of-adult-learning/

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies 2022,

Welcome to country, viewed 19 October 2022,

https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/welcome-country#

Bowers AP, Chan RJ, Herbert A, Yates P 2020, 'Estimating the prevalence of

life-limiting conditions in Queensland for children and young people aged

0-21 years using health administration data',

Australian Health Review

, vol. 44, pp. 630-6. DOI: 10.1071/AH19170.

Browning DM & Solomon MZ 2006, 'Relational learning in pediatric

palliative care: Transformative education and the culture of medicine',

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, vol.

15, pp. 795-815, DOI: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.03.002.

CareSearch & the QuoCCA project 2018,

Quality of Care Collaborative Australia

(QuoCCA), viewed 19 October 2022,

https://www.quocca.com.au/default.aspx

Curran VR & Sharpe D 2007, 'A framework for integrating

interprofessional education curriculum in the health sciences',

Education for Health (Abingdon, England),

vol. 20, pp. 93.

Dassah E, Aldersey H, McColl MA & Davison C 2018, 'Factors affecting

access to primary health care services for persons with disabilities in

rural areas: A "best-fit" framework synthesis',

Global Health Research and Policy

, vol. 3, pp. 36. DOI: 10.1186/s41256-018-0091-x.

Department of Health and Aged Care 2018,

The national palliative care strategy

, viewed 19 October 2022,

https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/the-national-palliative-care-strategy-2018

Ekberg S, Bowers A, Bradford N, Ekberg K, Rolfe M, Elvidge N, Cook R,

Roberts SJ, et al. 2021, 'Enhancing paediatric palliative care: A rapid

review to inform continued development of care for children with

life‐limiting conditions', Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health

, vol. 58, pp. 232-7. DOI: 10.1111/jpc.15851.

Mherekumombe MF 2018, 'From inpatient to clinic to home to hospice and

back: Using the "pop up" pediatric palliative model of care',

Children (Basel)

, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 55. DOI: 10.3390/children5050055.

Mherekumombe M, Frost J, Hanson S, Shepherd E & Collins J 2016, 'Pop

Up: a new model of paediatric palliative care',

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health

, vol. 52, pp. 979-82. doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13276

Miller GE 1990, 'The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance',

Academic Medicine, vol. 65, S63-7, DOI:

10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045.

Palliative Care Australia 2018,

Palliative care service development guidelines

, viewed 19 October 2022,

http://palliativecare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/02/PalliativeCare-Service-Delivery-2018_web2.pdf

Queensland Health 2019,

Queensland health palliative care services review: Key findings

, viewed 19 October 2022,

https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/852622/palliative-care-services-review-key-findings.pdf

Rosenberg JP, Mills J & Rumbold B 2016, 'Putting the 'public' into

public health: Community engagement in palliative and end of life care',

Progress in Palliative Care, vol. 24, pp. 1-3. DOI:

10.1080/09699260.2015.1103500.

Sansone HM, Ekberg S & Danby S 2022, 'Uncertainty, responsibility, and

reassurance in paediatric palliative care: A conversation analytic study of

telephone conversations between parents and clinicians',

Qualitative Health Communication

, vol. 1, pp. 26-43, DOI: 10.7146/qhc.v1i1.125538.

Slater PJ, Herbert AR, Baggio S, Donovan LA, McLarty AM, Duffield JA,

Pedersen LC, Duc JK, et al. 2018, 'Evaluating the impact of national

education in paediatric palliative care - The Quality of Care Collaborative

Australia', Advances in Medical Education and Practice, vol. 9,

pp. 927-41. DOI: 10.2147/AMEP.S180526.

Slater PJ, Osborne CJ & Herbert AR 2021, 'Ongoing value and practice

improvement outcomes from pediatric palliative care education: The Quality

of Care Collaborative Australia',

Advances in Medical Education and Practice

, vol. 12, pp. 1189-98. DOI: 10.2147/AMEP.S334872.

Stein A, Dalton L, Rapa E, Bluebond-Langner M, Hanington L, Stein KF,

Ziebland S, Rochat T, et al. 2019, 'Communication with children and

adolescents about the diagnosis of their own life-threatening condition',

The Lancet, vol. 393, pp. 1150-63, DOI:

10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33201-X.

[1]Country is the term often used by Aboriginal peoples to describe

the lands, waterways, and seas to which they are connected. The

term contains complex ideas about law, place, custom, language,

spiritual belief, cultural practice, material sustenance, family,

and identity (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Studies, 2022).