Emotion and feedback influence the learning landscape in sonography

Donna Oomens  1,4, Alison White

1,4, Alison White  2, Samantha Thomas

2, Samantha Thomas  3, Catherine Robinson

3, Catherine Robinson  4, Jillian Clarke

4, Jillian Clarke  1

1

Abstract

Introduction: Ultrasound is a rapidly expanding field that requires sonographers to continually update their skills through peer learning for optimal patient care. The exchange of skills between learner and teacher involves the cognitive, psychomotor and affective domains, which form a ‘learning landscape’. Significant literature is available regarding the first two of these, but the integration of affective skills (emotion and communication) is often overlooked. Feedback and feedback literacy are also factors contributing to and developing from the interaction. Therefore, our aim was to expand on our previous work to understand how the learning landscape and role of feedback impact Australian sonographers performing complex arteriovenous fistula (AVF) ultrasound examinations.

Methods: As previously reported, 50 surveys and 16 semi-structured interviews with Australian sonographers on their experience learning a new, complex ultrasound study (AVF) were linked, to report further in-depth findings of their learning experience and the effects of the learning landscape. Recruitment occurred via an Australian professional association. After transcribing the interviews, thematic analysis was conducted and integrated with the survey data.

Results: The combination of survey and interview data allowed the investigation off season-reported levels of competency and confidence,and how this aligned with learners’ subsequent positive and/or negative attitudes towards performing the new study, demonstrating both the influence of the support provided in the initial learning landscape, and the role of feedback / feedback literacy in consequent attitudes to towards the new skill.

Conclusion: The learning landscape significantly influences how learners perceive taught skills and process acquired knowledge. The importance of pedagogical support and resources for both peers and learners, in the areas of the affective domain and feedback literacy, is imperative in peer learning situations to optimise the learning experience.

Keywords: learning, emotions, feedback, ultrasonography, learning landscape

1 Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

2 School of Environment and Science, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia

3 Discipline of Women’s Health, University of New South Wales Medicine & Health, Randwick, Australia

4 School of Medicine, Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia

Corresponding author: Donna Oomens, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Level 7, West, Susan Wakil Building (D18), Sydney NSW 2006, Australia, [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

During the performance of an ultrasound examination, ultrasound practitioners / sonographers are required to actuate all the three learning domains of cognitive, psychomotor and affective skills to optimise examination accuracy and provide exceptional person-centred care (Hoque 2017; Thomson et al. 2024). The technical aspects of ultrasound examinations necessitate engagement of both the psychomotor and cognitive domains, while the physical assessment of the patient’s needs and emotional status requires accessing the affective domain (Hoque 2017; Price et al. 2010; Nicholls, Sweet & Hyett 2014). While sonographers in Australia are healthcare professionals who graduate at a level of technical and clinical competency determined by the relevant accrediting body (the Australian Sonographer Accreditation Registry [ASAR]), continuing technological advancements and the expanding scope of practice in the clinical workplace dictate that sonographers must continuously learn and master new skills post qualification (McGregor et al. 2020; Miles, Cowling & Lawson 2022). The quality of the acquired skills is influenced by the method of teaching, and this has an impact on the level of care delivered (Peak 2024).

Ongoing experiential learning by sonographers occurs in a dynamic and complex environment, termed the ‘learning landscape’ (Gruppen et al. 2019), that includes the pressures of maintaining a clinical workload and high standards of person-centred care and professionalism, all while continuously interacting with patients (Thomas, O’Loughlin & Clarke 2020). Having an experienced peer to guide learning enhances the workplace learning of sonographers; however, there is little evidence in the literature of best-practice principles for the structure or delivery of this style of immersive learning (Burnley & Kumar 2019). Pedagogical approaches to peer learning in the clinical environment have focused on the knowledge and skill transfer between the supervising peer, who can perform the skill (teacher or more knowledgeable other), and the learner, who is new to a particular skill. The learner may be a student or a qualified sonographer who is expanding their clinical skills with an advanced ultrasound examination.

The complexity of the learning landscape is further complicated by the need for nuanced communication between the teacher and learner (Sutkin et al. 2008). The teacher-learner relationship can be degraded by ineffective communication (non-verbal and interpersonal skills) hindering the learner’s skill attainment (Peak 2024). Conversely, learning is improved when the teacher is a skilled instructor who has a high teaching self- efficacy, effective communication and the ability to meet the unique challenges of teaching in the sonography environment (Peak 2024).

The emotional states of both the learner and the teacher have the potential to affect the value and success of the learning experience, delaying progression to mastery. The intertwining nature of the effective and cognitive domains in processing new skills is underpinned by the emotional state of both teacher and learner (Ajjawi et al. 2022; McConnell & Eva 2012). Learning and knowing in the cognitive domain are heavily influenced by emotions (affective domain), and furthermore, a deeper level of learning is cultivated when a positive emotion is linked to a learning experience (White, Humphreys & Oomens 2024; Kurtz 2022).

In their recent paper, Khine, Harrison and Flinton (2024) relayed the elevated benefits to learning reported by radiography and sonography students when their supervisors displayed interpersonal attributes of being approachable, encouraging, friendly, caring and non-judgemental, while Duque notes that skill acquisition is maximised in a calm environment (Duque et al. 2008). The British Medical Ultrasound Society Preceptorship and capability development framework for sonographers (2022, p. 19) further emphasises the specific personal and professional attributes required of a supervisor, stating they should be ‘calm, confident and non-judgemental’ and ‘have a willingness to share knowledge’. When learners feel supported by their sonographer peer, they are more likely to display a compassionate, empathetic and kind approach towards their patients (Van Der Westhuizen et al. 2020). Thus, indirectly, the perceived level of support that a learner receives from their teacher can influence the quality of care that their patients receive (Van Der Westhuizen et al. 2020).

In addition to the emotional aspects of the learning landscape, the quality and frequency of feedback provided to the learner is important for acquiring and mastering skills. Effective feedback provides the means to reduce the gap between the current performance and the desired outcome (Bosse et al. 2015; Burgess et al. 2020) and can prevent the embedding of poor skills (Burgess et al. 2020). This is best achieved in a co-creational learning dynamic between supervisors and learners (Ramani et al. 2019). Regular, consistent and timely feedback is critical for amplifying skill acquisition and deep learning by sonographers (Burnley & Kumar 2019).

Feedback literacy, described by Carless and Boud (2018, p. 1316) as ‘understandings, capacities and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies’ is crucial. Learners are more likely to receive feedback positively when they view it as accurate, which fosters positive emotions and prompts adaption and improvement in practice (Christensen-Salem et al. 2018). When individuals recognise improvement opportunities as learning moments, they are more likely to accept and incorporate feedback, embodying a growth mindset (Dweck 2006).

Emotional triggers (identity, relationship and truth) can affect feedback reception (Stone & Heen 2014). These triggers can interfere with feedback acceptance, compromising self-assessment and feedback regulation benefits (Dwyer 2021). Confidence and feelings of competency are linked to the level of understanding (Dunning et al. 2003). Lack of self-regulation or insight can result in overconfidence, which is linked to poorer patient outcomes (Schoenherr, Waechter & Millington 2018). Reflecting on feedback encourages acceptance and flexibility, leading to transformative learning with deeper meaning (Mezirow 1981; Wald 2015). Building an increased capacity for reflection can aid professional development and has been linked to enhanced levels of person-centred care (Van Der Westhuizen et al. 2020; Wald 2015).

This paper aims to explore the factors, such as emotion in the learning landscape and feedback in the sonography workplace, that are either supportive or preventative to the accurate acquisition of advanced sonography practices.

METHODS AND ANALYSIS

This paper draws on a survey study (Oomens, Thomas & Clarke 2022) and semi-structured interviews (Oomens, Thomas & Clarke 2024) that researched the experiences of sonographers learning to perform complex AVF ultrasound studies for the first time, analysing their original learning encounter, their interactions with other departments involved in the care of patients with AVF, and their current relationship with performing AVF studies. These studies have institutional ethics approval (2019/927).

In this paper, the results from the previous studies are synthesised for the purpose of providing a more detailed elaboration. Sonographers’ self- reported competency, understanding and initial influences are examined through the lens of their current attitudes towards performing the new ultrasound examination and perception of the role of feedback.

In 2020, a survey was advertised through the Australian Sonographers’ Association’s (ASA’s) online newsletter for three months. Prior to commencing the survey, prospective participants were directed to the Participant Information Statement (PIS), and volunteers interested in participating in a follow-up interview were directed to leave an email address. Of the 50 survey participants, 16 agreed to an interview, providing demographic data including gender, age and type of workplace.

Interview questions aimed to explore the learning landscapes in which Australian sonographers were taught and supported in the acquisition of AVF scanning skills. Other areas included the approach sonographers took to assessing an AVF (both physical assessment and ultrasound criteria); the relationship between experience and competence; and whether there was a difference (real or perceived) between confidence and competence. Interviewed participants were also encouraged to elaborate on areas important to them in their practice. Interviews were conducted using online Zoom (Version 5.0) and telephone, adhering to ethical requirements, during 2020 and 2021.

To facilitate thematic analysis, all interviews were transcribed by the first author and then coded using NVivo qualitative analysis software (QSR International, March 2020 release). Initial codes were reviewed by three of the authors (DO, JS, ST) discussed and cross-moderated between the researchers with the development of final themes ensuring validity. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022) allowed the researchers to develop the themes iteratively. Given the small size of the sonography profession in Australia, roughly half of the interviewees were to some extent known to the first author, but not to the remaining authors due to their different ultrasound streams.

RESULTS

From a pool of around 7,000 members of the ASA, 50 completed the initial survey. This response rate falls short of the typical web-based survey response rate of 25–30% (Daikeler, Bošnjak & Lozar Manfreda 2020). The relationship between demographic data of the survey respondents as compared to the 16 interviewees is presented in Table 1. The gender balance was representative of the wider profession (79:21% F/M) (ASA 2020). The workplace setting is skewed towards sonographers working in specialised vascular practices (40% v 2.3%) based on an email from ASAR.

Table 1: Comparison between ASA, survey and interview data

ASA |

Survey n=50 |

Interviews n=16 |

|

Female Male Other |

79% 21% |

79% 21% None reported |

75% 25% None reported |

Fulltime employment |

46% |

46% |

|

Location: |

|||

City/metro |

63% |

59.2% |

87.8% |

Regional towns |

31% |

24.5% |

12.2% |

Rural & remote |

6% |

16.3% |

0% |

Practice type: |

|||

Private |

72% |

48% |

62.5% |

Public |

25% |

46% |

18.8% |

Education/other |

3% |

6% |

18.8% |

Worktype: |

|||

General |

73.9% |

50% |

25% |

Vascular |

2.5% |

40% |

68.8% |

Other |

23.1% |

10% |

6.8% |

City/metro population > 100,000; Regional town population = 25,000–99,999; Rural & remote population < 25,000

SURVEY AND INTERVIEW DATA COMPARISON

The survey outcomes demonstrated that sonographers initially learned to scan AVF in several ways, as seen in Table 2.

Those who initially gained skills through independent learning via webinars felt they had a poor understanding of the AVF circuit. In comparison, only 21.4% of those gaining skills through a combination of methods rated themselves as having poor understanding. None of the participants who had extensive dedicated resources considered they had a poor understanding of the process. Access to learning support, in the form of a more experienced person or written guideline, varied by location, with 75% rural and remote sonographers having limited or no access, in contrast to only 25% of regional sonographers having no access to support.

The survey asked respondents whether there was anything that would increase their confidence when scanning an AVF. Almost half (47.3%) felt that gaining more hands-on practical experience through scanning a greater number of patients was essential. A further quarter (26.3%) indicated that they would like additional knowledge about how AVFs worked in a haemodynamic and physiological sense; however, they did not indicate how they might seek this knowledge. Several free text survey responses raised issues about the feedback respondents had received, prompting inclusion of questions on this topic in the interviews.

Table 2: Self-reported method of initial learning from the survey compared to learning landscape information from interviews

Survey n=49 (%) |

Interview n=16 (%) |

Well Supported |

Limited Support |

Sink or Swim |

|

Don’t perform |

3 (6.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|||

Self-taught |

4 (8.1%) |

1 (6.2%) |

1 |

||

Taught by vascular surgeon |

4 (8.1%) |

1 (6.2%) |

1 | ||

Taught by sonographer |

19 (38.7%) |

6 (37.5%) |

3 |

1 |

3 |

Webinar |

1 (2.0%) |

2 (12.6%) |

1 |

1 |

|

Independent reading |

1 (2.0%) |

0 (0%) |

|||

Extensive dedicated resources |

3 (6.1%) |

2 (12.5%) |

1 |

1 |

|

Combination of methods |

14 (28.5%) |

4 (25%) |

1 |

2 |

INTERVIEW DATA

Demographics from the 16 interview participants are presented in Table 1, including differences in demographics reported in the ASA/ASAR, the survey and the interview data. There was a greater proportion of interviewed sonographers working in both major metropolitan centres and vascular laboratories compared to the proportions reported in the survey data and ASA information.

Based on the interviews, there were three major themes:

- Impact of the learning landscape on future attitudes to AVF scanning

- Feedback and its role in sonographer development

- The interplay between competency and confidence

The first two themes are further explored in this paper, by combining interview and survey data. The interviews raised new ideas around the delivery and reception of feedback and the relationship with the learning landscape. Theme 3 has been described previously (Oomens, Thomas & Clarke 2024).

Theme 1 –Learning Landscape

The learning landscape was divided into three categories, based on the initial style of teaching received. The three categories were:

- Well supported. This entailed individual support from a supervisor with ongoing resources beyond the initial learning experience.

- Limited support. A situation where some support was provided, but this was not ongoing.

- Sink or swim. In this category no support was provided to learners.

The interview questions included what the current feelings of the participants were towards performing AVF examinations. The responses were divided into positive and negative feelings, with nine of the 16 responses negative.

All participants in the ‘well supported’ group (n = 4) had positive feelings towards performing AVF examinations, while 66% of those in the ‘sink or swim’ group (n = 9) had negative feelings around performing these studies. All of the ‘limited support’ group (n = 3) had negative feelings towards performing AVF examinations.

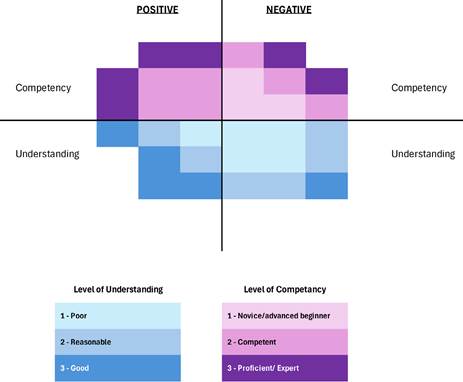

This was further correlated with information in the survey on self- reported confidence and competency. This is demonstrated in Figure 1, where competency in scanning AVF is displayed above the X-axis, and level of understanding of AVF below. Both are divided by the Y-axis into positive/ negative attitudes. The level of competency and understanding is depicted by the colour saturation. This allows for a visual representation of the frequency of the levels of competency and understanding. Figure 1 shows there is a higher concentration of reasonable or good understanding and higher self-reported competency levels in the positive group. Most of the poor understanding levels fell in the negative group with only one of the five reported as positive. Similarly, within the competency display, in the positive group, all are either ‘competent’ or ‘proficient’, while all of those who answered ‘novice’ or ‘advanced beginner’ fell into the negative group.

Figure 1: Confidence and Competency levels by current attitudes

Theme 2 –Feedback

Feedback and its role in sonographer development was explored by asking what type of feedback had been provided, and the preferred method of receiving feedback. From this it was determined that feedback was either extrinsic, that is, delivered by another person (usually a supervising sonographer or doctor) or intrinsic, driven by the learner themselves in a feedback-seeking manner. The eight who pursued intrinsic feedback used pro-active vocabulary to describe its influence, and how it helped them improve their future performance.

The type of feedback supplied in the extrinsic setting fulfilled more of an evaluation process with comments on right or wrong but no insight on how to attain improved performance.

There was a small cohort of participants (12.5%) who received no feedback or who worked within a practice that did not prioritise feedback, due to time constraints. Only one learner reported having a more experienced sonographer to support their skill development. This single learner’s experience was closest to the ideal as they were able to ask questions and develop a plan for improvement.

DISCUSSION

While the initial survey study (Oomens, Thomas & Clarke 2022) found that there were multiple initial methods of learning, those who had had to learn independently or with minimal support rated themselves as having poorer understanding of the skill, while those in supported environments self-rated their competency and confidence levels as higher. The paper (Oomens, Thomas & Clarke 2024) that reported on the interview data, demonstrated a link between the level of support and feedback, and current attitudes. This paper analysed both the survey and interview studies, with the aim of further understanding the impacts of the learning landscape and feedback literacy, so that sonographer supervisors can include this in their teaching practice.

There was a significant interplay between the initial exposure to the new AVF skill and the degree of structure of feedback in the learning landscape, which in turn, influenced and impacted emotions at the learning and self- regulation stages of development. As the learning landscape and feedback contribute to understanding and competency levels, this relationship was also explored. Those learners who experienced a supportive style of learning described the experience positively (Table 2), reflecting the Vygotskian theory that this style of supportive learning allows a learner to develop beyond what is possible without support (Sanders & Welk 2005). This theory, which can be referred to as scaffolding, holds that a teacher (in this context the supervisor sonographer) provides support and social interaction, which is gradually reduced as the learner achieves mastery (Sanders & Welk 2005). When the teacher is more knowledgeable and provides concrete steps to acquiring a skill, there is a reduced cognitive load for the learner (van Nooijen et al. 2024). The presence of high levels of complexity and interactivity, combined with a high emotional load, have been shown to interfere with learning (Basu Roy & McMahon 2012, Fraser et al. 2012). These factors can be present when learning new ultrasound skills, particularly in the context of complex procedures such as an AVF. This reinforces the concept that a goal for supervisors is to create a learning environment that is conducive to deeper learning, in which negative emotional states, such as fear and anxiety, are avoided, as a means of lowering the emotional load of the student.

All too often, the impact of teaching styles goes unrecognised in the clinical environment, despite the assertion that life-long learning in sonography occurs when the quality of training and support is valued in the clinical workplace (ASA 2015). In comparison with other allied health professions, sonography lacks a defined model prescribing how clinical supervisors can provide and maintain learning in the clinical environment (Khine, Harrison & Flinton 2024). Sonographers also often lack formalised education in training and supervision, which can result in a lack of the skills necessary to effectively supervise (Williamson 2018). The lack of education for clinical sonography supervisors on how to teach has the potential to significantly diminish the quality of learning, decreasing motivation and engagement with learning (Williamson 2018; Khine, Harrison & Flinton 2024; Peak 2024). In our study, those who felt they had a lower level of understanding and competency were more likely to have a negative attitude to the skill (Figure 1).

Moreover, there is a lack of policy documents in Australia that specify the requirements of the role of a clinical supervisor. The ASA’s guideline: A sonographer’s guide to clinical supervisors (2015) aims to fill this gap and provide some direction in the area of supervision. It emphasises that for optimal learning in the sonography workplace, supervisors need to be supported in their own professional development to become more skilled in educational practice. This, in turn, facilitates greater development of learners and can lead to the delivery of a higher level of person-centred care (ASA 2015). Thus, attention should be given to ensuring the ongoing development of supervisors, as this is no less important than developing newly qualified staff. Prioritising ongoing development for supervisors allows for the ability to ‘maximise their potential and practise at the highest level possible within an individual scope of practice’ (British Medical Ultrasound Society 2022, p. 22).

Both teaching styles and the learning landscape impact a learner’s emotional state. The ability to learn is additionally impacted by the potential to reject feedback, due to the emotional state induced by the initial learning experience. It is imperative that feedback is provided in a manner that recognises this impact and actively works to overcome it (Ajjawi et al. 2022). The results of the interviews demonstrate varying views on what constitutes effective and acceptable feedback, as well as the way to approach feedback. This is underscored by the fact that only one interview response described ongoing dialogue as a form of feedback.

Two sub-themes were identified through the interview questions surrounding feedback, both of which are consistent with the medical education literature. The group of eight participants who relied on intrinsic drivers to ask for feedback had evidently developed self-regulating and reflective skills that enabled the confidence to seek out feedback, thus furthering their continual learning. Feedback-seeking behaviour is also likely to increase job satisfaction and foster faster skill acquisition (Balon 2022). The remaining participants were more passive, accepting the feedback format that was delivered to them even when there were no options for advancing their knowledge or skill set. The goal of supervisors in the clinical workplace should be the provision of quality feedback with encouragement of feedback-seeking behaviour, to harness and promote change in learner practice and behaviour.

The process of giving quality feedback is covered extensively in the literature (Ajjawi et al. 2022) with varying perspectives around ideal format delivery, degree of sensitivity, and relevancy. This range of ideals can make it difficult for a supervisor to navigate the best approach to providing feedback, but at the least, it needs to be timely, based on observation, constructive and specific (Schuler 2021).

The role of feedback from a supervisor in the development of higher-level skills in learners should not be underestimated (Edwards, Chamunyonga & Clarke 2018). Ideally the ‘learner and educator work together to reach goals and collectively create opportunities to use feedback in practice. An enduring relationship built on the foundation of honesty and trust is necessary to facilitate the educational alliance’ (Jug, Jiang & Bean 2019, p. 245). Furthermore, when giving feedback it is imperative to be clear that you are doing so and have an action plan in place, providing a goal for the learner to work towards (Jug, Jiang & Bean 2019). Consistency and frequency of feedback to the learner in a clinical setting is a critical component in the development of sonographic skills (Burnley & Kumar 2019).

The way in which a learner interprets and reacts to feedback can either enhance or diminish the potential impact for learning (Hardavella et al. 2017). This reaction is subject to the emotional state of the learner, which mirrors the impact of emotion in the learning. When learners thought feedback was unfair or derogatory, they reported having strong negative emotions (Johnson et al. 2016).

There is evidence in the literature of the discrepancy between educators delivering feedback believing they are doing a good job, (Johnson et al. 2016; Ramani & Krackov 2012) while those on the receiving end believe the feedback is poor or incorrect (Balon 2022; Tripodi et al. 2021). Eva and coworkers describe the complex interactions between levels of confidence, fear and ability to reason that occur when receiving feedback (Eva et al. 2011). This is evidenced in healthcare, where experienced professionals assume that their practice does not require improvement (Eva et al. 2011; Jug, Jiang & Bean 2019). In the presence of continual negative feedback, students may disengage with the process, and this has the potential for life-threatening consequences (Peacock et al. 2012). Any such disengagement with the feedback process may result in a decrease in clinical skills and therefore has the potential to cause serious health outcomes, such as in patients with an AVF that are reliant on a well- functioning fistula for life-preserving treatment (Visciano et al. 2014).

The absence of effective feedback for half of our cohort, or worse, the absence of any feedback at all, has the potential to generate significant detrimental flow-on affects in the development of the learner. They may incorrectly assume that their practice is competent and therefore will see no need to change their practice or their behaviour. This is particularly relevant given just under half (47%) of the participants felt that simply performing more studies would make them better at the skill. In the published survey results (Oomens, Thomas & Clarke 2022) 10% considered themselves experts, while indicating they had minimal understanding of AVF flow dynamics. This potential overestimation of their level of skill can have the direct effect of decreasing accuracy and quality of care for the patient (Cantillon & Sargeant 2008; Jug, Jiang & Bean 2019).

The role of the organisation, employer or department is recognised in this study with many reporting the lack of priority that further education and feedback appears to have in their workplace. The lack of priority, time and ability to give and receive feedback is in direct disconnect with the desire of sonographers to receive a greater quantity of feedback on their clinical work (Burnley & Kumar 2019). Organisations need to recognise that additional resources must be provided to enable and promote a culture of feedback (ASA 2015). Equally, it is important to not confuse evaluation with feedback (Jug, Jiang & Bean 2019). A clear understanding should be held by all parties of the difference between feedback and evaluation, and the feedback should not be given as remediation or discipline, but for the purpose of continual development (Ramani et al. 2019; Jug, Jiang & Bean 2019).

Guiding principles for the relationship between the supervisor and learner in the clinical environment are that it is characterised by collaboration and reflection, focused on future goals, and promotes development rather than performance (Zajac et al. 2021). To achieve the optimal learning relationship requires strength and commitment in workplaces to allocate sufficient resources in three essential areas: 1. provision of up-to-date pedagogy, 2. supportive learning landscapes and 3. effective feedback that incorporates understanding of triggers. Critically, reflection and reassessment of the learning environment should occur regularly over time to ensure currency of the intended learning and the achievement of learning goals (Zajac, et al. 2021).

CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to understand the impact of all facets of the initial learning landscape, which is often grounded in peer learning, for Australian sonographers learning the skill of AVF examinations. Recommendations from this study are multi-factorial and are derived from the integration of survey findings with interview data. They include the need for supervisors to understand the influence of the learning landscape on the learners to decrease negative emotional states through a reduction of cognitive impact. In addition, our cohort showed the need for learners to be active participants in seeking feedback. We also learned that triggers for rejecting feedback are complex and influence the incorporation of feedback. All of these issues can play a vital role in ensuring or diminishing the quality of practice in the clinical workplace. To optimise person-centred care, organisations need to appreciate the value of both the initial learning landscape through peer learning, and feedback, by providing an enabling environment for these activities to occur so that continuous learning is encouraged.

LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

A limitation of this study was the small participant cohort, sourced from the Australian sonographer workforce, which may not represent either the broader Australian community, nor international training models, therefore limiting the ability to generalise. Additionally, there is the potential that the findings were skewed due to the method of recruiting participants, relying on the participation of those interested in the topic.

Importantly, this study highlights the need for the promotion of learning resources, for both the learner and supervisor, to improve peer learning and feedback.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare. No funding was received for this project.

References

AjjawI, R, Kent, F, Broadbent, J, Hong-Meng Tai, J, Bearman, M & Boud, D 2022, ‘Feedback that works: a realist review of feedback interventions for written tasks’, Studies in Higher Education, vol. 47, pp. 1343-1356.

Australasian Sonographers Association 2015, ASA Guideline: A sonographer’s guide to clinical supervision, Viewed 25 October 2020, https://www.sonographers.org/publicassets/62af4f20-2a85-ea11-90fb- 0050568796d8/Clinical_Supervision_Guidelines.pdf

Australasian Sonographers Association, 2020, Employment and Salary, Viewed 25 October 2020, https://www.sonographers.org/research/ sonography-research/employment-and-salary

Australian Sonographers Accreditation Registry 2019, Lunnay, G, email, 28 March, [email protected]

Balon, R 2022, ‘A crucial part of the conversation in education: receiving feedback’, Academic Psychiatry, vol. 46, pp. 273-5.

Basu Roy, R & McMahon, GT 2012, ‘High fidelity and fun: but fallow ground for learning?’ Medical Education, vol. 46, pp. 1022-3.

Bosse, HM, Mohr, J, Buss, B, Krautter, M, Weyrich, P, Herzog, W, Junger, J & Nikendei, C 2015, ‘The benefit of repetitive skills training and frequency of expert feedback in the early acquisition of procedural skills’, BMC Medical Education, vol. 15, pp. 1-10.

Braun, V & Clarke, V 2022, Thematic analysis, SAGE Publications Ltd., London.

British Medical Ultrasound Society 2022. Preceptorship and Capability Development Framework for Sonographers.

Burgess, A, Van Diggele, C, Roberts, C & Mellis, C 2020, ‘Tips for teaching procedural skills’, BMC Medical Education, vol. 20, pp. 1-6.

Burnley, K & Kumar, K 2019, ‘Sonography education in the clinical setting: the educator and trainee perspective’, Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, vol. 22, pp. 279-85.

Cantillon, P & Sargeant, J 2008, ‘Giving feedback in clinical settings’, BMJ, vol. 337, pp. 1292-4.

Carless, D & Boud, D 2018, ‘The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 43, pp. 1315-25.

Christensen-Salem, A, Kinicki, A, Zhang, Z & Walumbwa, FO 2018, ‘Responses to feedback: the role of acceptance, affect, and creative behavior’, Journalof Leadership & Organizational Studies, vol. 25, pp. 416-429.

Daikeler, J, Bošnjak, M & Lozar Manfreda, K 2020, ‘Web versus other survey modes: an updated and extended meta-analysis comparing response rates’, Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, vol. 8, pp. 513-39.

Dunning, D, Johnson, K, Ehrlinger, J & Kruger, J 2003, ‘Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence’ Current Directions of Psychological Science, vol. 12, pp. 83-87.

Duque, G, Fung, S, Mallet, L, Posel, N & Fleiszer, D 2008, ‘Learning while having fun: the use of video gaming to teach geriatric house calls to medical students’. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 56, pp. 1328-32.Dweck, CS 2006, Mindset : the new psychology of success, Random House, New York.

Dwyer, LP 2021, ‘Turning the table: developing students’ skills in receiving feedback’, Management Teaching Review, vol. 6, pp. 317-29.

Edwards, C, Chamunyonga, C & Clarke, J 2018, ‘The role of deliberate practice in development of essential sonography skills’, Sonography, vol. 5, pp. 76-81.

Eva, KW, Armson, H, Holmboe, E, Lockyer, J, Loney, E, Mann, K & Sargeant, J 2011, ‘Factors influencing responsiveness to feedback: on the interplay between fear, confidence, and reasoning processes’, Advances in Health Sciences Education vol. 17, pp. 15-26.

Fraser, K, Ma, I, Teteris, E, Baxter, H, Wright, B & McLaughlin, K 2012, ‘Emotion, cognitive load and learning outcomes during simulation training’, Medical Education, vol. 46, pp. 1055-62.

Gruppen, LD, Irby, DM, Durning, SJ & Maggio, LA 2019, ‘Conceptualizing learning environments in the health professions’, Academic Medicine, vol. 94, no. 7, pp. 969-74.

Hardavella, G, AamliI-Gaagnat, A, Saad, N, Rousalova, I & Sreter, KB 2017, ‘How to give and receive feedback effectively’. Breathe, vol. 13, pp. 327-33.

Hoque, M 2017, ‘three domains of learning: cognitive, affective and psychomotor’, The Journal of EFL Education and Research, vol. 2, pp. 45-51.

Johnson, CE, Keating, JL, Boud, DJ, Dalton, M, Kiegaldie, D, Hay, M, McGrath, B, McKenzie, WA, Nair, KBR, Nestel, D, Palermo, C & Molloy, EK 2016, ‘Identifying educator behaviours for high quality verbal feedback in health professions education: literature review and expert refinement’, BMC Medical Education, vol. 16, pp. 1-11

Jug, R, Jiang, XS & Bean, SM 2019, ‘Giving and receiving effective feedback: a review article and how-to guide’, Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, vol. 143, pp. 244-50.

Khine, R, Harrison, G & Flinton, D 2024, ‘What makes a good clinical practice experience in radiography and sonography? An exploration of qualified clinical staff and student perceptions’, Radiography, vol. 30, pp. 66-72.

Kurtz, A 2022, ‘Feeling and learning: a study of students’ emotions in the sonography classroom’, Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography, vol. 38, pp. 247-255.

McConnell, M & Eva, KW 2012, ‘The role of emotion in the learning and transfer of clinical skills and knowledge’ Academic Medicine, vol. 87, pp. 1316-22.

McGregor, R, Pollard, K, Davidson, R & Moss, C 2020, ‘Providing a sustainable sonographer workforce in Australia: clinical training solutions’, Sonography, vol. 7, pp. 141-7.

Mezirow, J 1981, ‘A critical theory of adult learning and education’, Adult Education, vol. 32, pp. 3-24.

Miles, N, Cowling, C & Lawson, C 2022, ‘The role of the sonographer –an investigation into the scope of practice for the sonographer internationally’, Radiography, vol. 28, pp. 39-47.Nicholls, D, Sweet, L & Hyett, J 2014, ‘Psychomotor skills in medical ultrasound imaging an analysis of the core skill set’, Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, vol. 33, pp. 1349-52.

Oomens, D, Thomas, S & Clarke, J 2022, ‘Ultrasound of dialysis fistulae: factors influencing Australian practice’, Sonography, vol. 9, pp. 16-22.

Oomens, D, Thomas, S & Clarke, J 2024, ‘Professional development of advanced sonography skills in the performance of arterio-venous fistula studies: the role of the learning landscape, feedback and emotion’, Sonography, vol. 11, pp. 305-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/sono.12436

Peacock, S, Scott, A, Murray, S & Morss, K 2012, ‘Using feedback and ePortfolios to support professional competence in healthcare learners’, Research in Higher Education Journal. vol. 16, pp. Jan-23.

Peak, K 2024, ‘The ability for teaching self-efficacy by clinical preceptors in diagnostic medical sonography’, Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography, vol. 40, pp. 38-46.

Price, S, Ilper, H, Uddin, S, Steiger, HV, Seeger, FH, Schellhaas, S, Heringer, F, Ruesseler, M, Ackermann, H, Via, G, Walcher, F & Breitkreutz, R 2010, ‘Peri-resuscitation echocardiography: training the novice practitioner’, Resuscitation, vol. 81, pp. 1534-9.

Ramani, S, Könings, KD, Ginsburg, S & Van Der Vleuten, CP 2019, ‘Feedback redefined: principles and practice’, Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 34, pp. 744-9.

Ramani, S & Krackov, SK 2012, ‘Twelve tips for giving feedback effectively in the clinical environment’, Medical Teacher, vol. 34, pp. 787-91.

Sanders, D & Welk, DS 2005, ‘Strategies to scaffold student learning: applying Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development’, Nurse Educator, vol. 30, pp. 203-7.

Schoenherr, JR, Waechter, J & Millington, SJ 2018, ‘Subjective awareness of ultrasound expertise development: individual experience as a determinant of overconfidence’, Advances in Health Sciences Education, vol. 23, pp. 749-65.

Schuler, MS 2021, ‘The reflection, feedback, and restructuring model for role development in nursing education’, Nursing Science Quarterly, vol. 34, pp. 183-8.

Stone, D & Heen, S 2014, Thanks for the feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well, Viking Books, New York.

Sutkin, G, Wagner, E, Harris, I & Schiffer, R 2008, ‘What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature’, Academic Medicine, vol. 83, pp. 452-66.

Thomas, S, O’Loughlin, K & Clarke, J 2020, ‘Sonographers’ level of autonomy in communication in Australian obstetric settings: does it affect their professional identity?’ Ultrasound, vol. 28, pp. 136-44.

Thomson, S, MacPherson, L, Thomas, S & Christoffersen, A 2024, ‘Person- centred ultrasound communication’, in S Chau, E Hyde, K Knapp & C Hayre (eds.) Person-centred care in radiology international perspectives on high- quality care. 1st ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Tripodi, N, Feehan, J, Wospil, R & Vaughan, B 2021, ‘Twelve tips for developing feedback literacy in health professions learners’, Medical Teacher, vol. 43, pp. 960-5.Van Der Westhuizen, L, Naidoo, K, Casmod, Y & Mdletshe, S 2020, ‘A qualitative approach to understanding the effects of a caring relationship between the sonographer and patient’, Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, vol. 51, pp. S53-8.

Van Nooijen, CCA, De Koning, BB, Bramer, WM, Isahakyan, A, Asoodar, M, Kok, E, Van Merrienboer, JJG & Paas, F 2024, ‘A cognitive load theory approach to understanding expert scaffolding of visual problem-solving tasks: a scoping review’, Educational Psychology Review, vol. 36, pp. 12.

Visciano, B, Riccio, E, De Falco, V, Musumeci, A, Capuano, I, Memoli, A, Di Nuzzi, A & Pisani, A 2014, ‘Complications of native arteriovenous fistula: the role of color Doppler ultrasonography’. Therapeutic Apheresis and Dialysis, vol. 18, pp. 155-61.

Wald, HS 2015, ‘Refining a definition of reflection for the being as well as doing the work of a physician’, Medical Teacher, vol. 37, pp. 696-9.

White, A, Humphreys, L & Oomens, D 2024, ‘Building emotional resilience to foster well-being by utilising reflective practise in the sonography workplace’, Sonography. vol. 11, pp. 243-50. https://doi.org/10.1002/ sono.12405

Williamson, JM 2018, ‘Are senior cardiac sonographers adequately prepared to provide echo training and supervision to students? Survey results from senior cardiac sonographers and echo educators in Victoria, Australia’, Sonography, vol. 5, pp. 12-19.

Zajac, S, Woods, A, Tannenbaum, S, Salas, E & Holladay, CL 2021, ‘Overcoming challenges to teamwork in healthcare: a team effectiveness framework and evidence-based guidance’, Frontiers in Communication, vol. 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.606445