Organisational Learning Approaches in Healthcare Organisations: A Scoping Review

Debra Palesy![]() 1, Margaret E Crowley

1, Margaret E Crowley![]() 2

2

Abstract

Purpose: Despite years of analysis and debate, the concept of organisational learning (OL) still lacks a theoretical basis and little information is provided in the way of hands-on application for practitioners. Perceived benefits of OL have been reported, yet very few standardised approaches proposed. This review synthesises the literature on standardised approaches to OL.

Methodology: Two research questions guided the review: (1) what OL models, frameworks or approaches currently exist?; and (2) what are the common enablers among these models, frameworks or approaches that might best support OL in a healthcare context? Using a systematic screening and reporting process, 360 pieces of literature were analysed and a final 26 articles were included for review.

Results: Seven different OL models, frameworks and/or approaches were identified. Multi-component models were reported most frequently, although this category itself encompasses a wide range of approaches. From these models, frameworks and/or approaches, 14 key enablers were extracted and synthesised into three levels: individual, group and organisational.

Practical Implications: There was considerable overlap among all OL models, frameworks and/or approaches identified in the literature, rendering it difficult to synthesise the findings into a single standardised approach. Consideration of OL enablers appeared to be less difficult. These enablers may inform a number of strategies for supporting OL in the healthcare context. Regular appraisal of the effectiveness of these enablers across organisational departments, teams and levels will assist in determining the extent and quality of OL.

Limitations: The OL literature remains dominated by persuasive and/or analytical papers, rather than theory development, and does not provide hands- on knowledge for practitioners seeking to enact OL models. Many papers used the terms ‘organisational learning’ and ‘learning organisation’ interchangeably, so relevant material may have been excluded.

Keywords: organisational learning, standardised, approach, review

1 University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia

2 Health Education and Training Institute, NSW Health, St Leonards, Australia

Corresponding author: Dr Debra Palesy, PO Box 7100, Toowoon Bay NSW 2261, Australia, [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING DEFINED

The term ‘organisational learning’ (OL) appears to have been first used in 1963 by Cyert and March in their seminal study of the behavioural aspects of organisational decision making (Easterby-Smith & Lyles 2011), and since then has given rise to a range of theoretical perspectives (e.g., Argyris & Schön 1978; Crossan, Lane & White 1999; Fiol & Lyles 1985; Lave & Wenger 1991; Nonaka 1994). Despite the increasing interest from researchers and practitioners, a broadly accepted theory of OL has yet to emerge (Doyle, Kelliher & Harrington 2015).

For the purpose of this literature review, OL is defined as an organisationally regulated, collective process of acquiring, retaining/ storing, and disseminating or transferring knowledge within an organisation (Basten & Haamann 2018; Huber 1991). As part of this process, individual and group-based learning experiences aimed at improving organisational performance or achieving organisational goals are arranged into organisational procedures, practices and structures, which may in turn inform the future learning activities of the organisation’s members (Basten & Haamann 2018). OL is also considered to have three defining attributes: OL brings about positive change (Huber 1991); this change is related to knowledge, cognition and/or action (Argote & Miron-Spektor 2011); and this occurs within the context of an organisation (Argote & Miron-Spektor 2011).

ORGANISATIONAL LEARNING VS LEARNING ORGANISATION

Prior to the mid-1990s, the terms ‘organisational learning’ and ‘learning organisation’ were used interchangeably, before being separated into two specialties (Alerasoul et al. 2022). Some argue that OL is an ongoing process or activity, that is, how organisations learn (Örtenblad 2001; Sun 2003), while the learning organisation is about an ideal structure, in which the learning processes are already effective (Sun 2003; Tsang 1997). In any case, there is a simple relationship between the two: learning organisations are proficient at OL (Tsang 1997). That is, effective OL must be embedded within the views of the organisation held by its members, along with the epistemological elements found in the organisational environment (Argyris & Schön 1978).

THE CASE FOR A STANDARDISED APPROACH TO OL IN HEALTHCARE ORGANISATIONS

While the literature has both criticised and supported OL over the decades (Schilling & Kluge 2009), a standardised approach may be key to improving safety and quality in healthcare organisations (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC] 2019). A range of impediments to OL have been proposed, including individual factors, for example, attitudes, thinking and behaviour; organisational impediments, for example, strict work rules and regulations, narrow role scope, blame cultures; and societal-environmental influences, for example, technological changes, complex and dynamic external environments (Lawrence et al. 2005; Schilling & Kluge 2009).

Others are more positive about the potential of OL. Effective OL offers at least five advantages: adaptability and agility (Hsu & Pereira 2008; Zhao et al. 2014), innovation and creativity (Alerasoul et al. 2022; Fiol & Lyles 1985), enhanced problem solving (Zhao et al. 2014), increased staff engagement and retention (Alerasoul et al. 2022), and organisational resilience (Chen 2005; Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). Besides uplifting workforce capability, in healthcare organisations these advantages have the potential to reduce costs to the health care system and improve patient safety (ACSQHC 2019).

AIM OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW AND GUIDING QUESTIONS

The impetus for this review relates to a key priority of the NSW Health Workforce Plan 2022 –2032, to ‘(e)quip our people with the skills and capabilities to be an agile, responsive workforce’ (Ministry of Health 2022, p. 14). Supporting activities for this priority include ‘(u)plifting workforce capability through a standardised approach to organisational learning’ (Ministry of Health 2022, p.14), the central premise for this review.

Two research questions are informed by the central premise and were used to guide this review:

- What OL models, frameworks or approaches currently exist?

- What are the common enablers among these models, frameworks or approaches that might best support OL in a healthcare context?

Literature collected and analysed in relation to these questions articulate a standardised approach to OL that may uplift workforce capability.

METHODOLOGY

DESIGN

Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) methodological framework for scoping reviews informed the literature review. This five-stage framework relies on:

- identifying the research question(s)

- identifying relevant studies

- study selection

- charting the data

- collating, summarising and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley 2005).

This methodology was chosen as the most appropriate, since the review is mostly concerned with the identification, mapping, reporting and discussion of certain OL characteristics in papers or studies (Colquhoun et al. 2014; Munn et al. 2018).

SEARCH TERMS

Search terms were determined by discussion among the two reviewers (one with a background in nursing and education, the other with a background in education, health workforce development and management) and a senior librarian. After trying several combinations which returned tens of thousands of results, along with the decision to eliminate the literature on learning organisations (i.e., the structure) to focus on OL (i.e., process), the final search terms were:

- Organisational/organizational learning; and

- Framework; or

- Model; or

- Approach.

An extensive title and/or abstract search of the following databases: Academic Search Complete, Business Source Complete, Education Source and ERIC (via EBSCO) was conducted in December 2023 and January 2024. Individualised search strategies were developed according to the indexing terms and search syntax of each database, including Boolean operators and truncations. Manual searches of related articles and other papers citing included references, as well as bibliographic mining were conducted.

INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Due to the large numbers of results, publications were considered for inclusion if they met the following criteria: search terms found in the title only; peer reviewed papers, that is, no books, reports, opinion pieces, guidebooks, dissertations, learning modules or review protocols; available in English language; and any publication year acceptable, although EBSCO automatically determined the year limit to be from 1950 onwards.

Also due to the plethora of available literature, we excluded publications that discussed OL related to universities or university courses, schools, students and recognition of prior learning. Papers that discussed OL in ‘colleges’ were considered as they sometimes referred to community colleges, open learning and distance learning institutions. Change management pieces, performance reviews, benchmarking, accreditation and any article about employee behaviour were excluded; along with any publication in which OL frameworks were mentioned but only in relation to another concept (e.g., behaviour, market behaviour, corporate enterprise software/product development); articles that evaluated well-known frameworks already identified; and pieces that simply described OL.

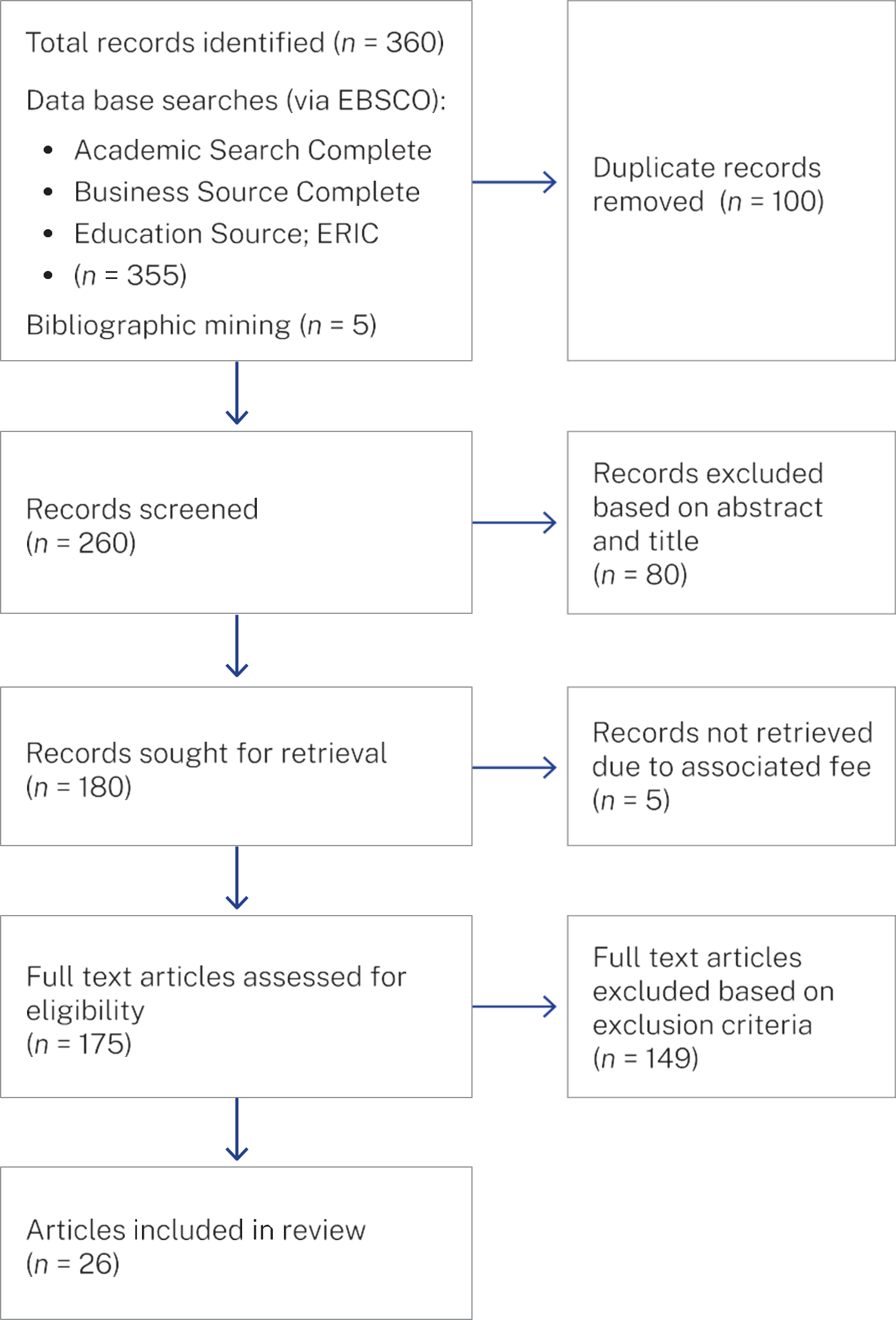

DOCUMENT SELECTION

A systematic screening process was conducted whereby initial search results were screened for eligibility first by title, then by abstract (if available and/or relevant), and finally by full text. Document eligibility was determined by the principal reviewer, while the second reviewer was consulted to achieve consensus when discrepancies arose. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) adapted from Page et al. (2021) was used to inform the flow chart literature identification and selection (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow chart leading to document selection

DATA EXTRACTION

Key information extracted from the 26 final records included the citation, type of publication, OL framework and overview (Appendix 1). The principal reviewer extracted the information from the articles, while the second reviewer checked the extracted information for accuracy and completeness.

SEARCH RESULTS

TYPES OF PUBLICATIONS

The 26 publications were classified as persuasive and/or analytical papers (i.e., analysed OL concepts and proposed OL approaches, models or frameworks) (19); research papers (5); a conceptual analysis (1) and a literature review (1).

TYPES OF MODELS, FRAMEWORKS AND/OR APPROACHES

Models, frameworks and/or approaches found within the 26 publications were either conceptual, synthesised from seminal works in the OL literature, or offered practical applications, for example, to hospitals, government departments, aviation industries or logging industries. Seven different models, frameworks and/or approaches were identified in the reviewed literature: multi-component (received eight citations); integrated (six citations); action learning/cyclical (three citations); knowledge-focused (three citations); socio-cognitive (three citations); cognitive (two citations) and social (one citation). A summary of all OL models, frameworks and/ or approaches identified in the literature, ordered by the frequency of citations, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of OL models, frameworks and/or approaches

Model, Framework, Approach |

Citations |

Multi-component |

Babaeinesami & Ghasemi (2021); Chen (2005); Chou & Ramser (2019); Crossan, Lane & White (1999); Edwards (2017); Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera (2005); Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002); Mulholland et al. (2000) |

Integrated |

Jenkin (2013); Kaur & Hirudayaraj (2021); Kim (1993); Lawrence et al. (2005); Lewis (2014); Zietsma et al. (2002) |

Action learning/cyclical |

Law & Gunasekaran (2009); Murray (2002); Schumacher (2015) |

Knowledge-focused |

Duffield & Whitty (2016); Malone (2002); Nonaka (1994) |

Socio-cognitive |

Akgün, Lynne & Byrne (2003); Argote & Miron-Spektor (2011); Cho et al. (2013) |

Cognitive |

Provera, Montefusco & Canato (2010); Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier (1997) |

Social |

Williams (2001) |

Fourteen common themes were extracted from the literature in relation to key enablers within the OL models, frameworks and/or approaches. Ordered by the frequency of citations, these were: knowledge-management activities, e.g., knowledge, skill or information acquisition, processing, retaining and dissemination (9); shared mental models (9); shared vision (9); collaboration (8); communities of practice (6); leadership (6); organisational systems, e.g., technology, infrastructure, routines (6); reflection (5); fostering a learning culture (5); feed forward and feedback mechanisms (4); learning from errors (4); team learning (3) and problem solving (1). These themes, along with the citing literature, can be found in Table 2. A snapshot of the themes cited across the OL models/frameworks and/or approaches can be found in Table 3.

Table 2: Key enablers of OL models, frameworks and/or approaches

KeyEnablers |

Models Reporting |

Citations |

Knowledge management |

Multi-component |

Chen (2005); Mulholland et al. (2000) |

Integrated |

Jenkin (2013); Lewis (2014) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Nonaka (1994) |

|

Socio-cognitive |

Akgün, Lynne & Byrne (2003); Argote & Miron-Spektor (2011) |

|

Cognitive |

Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier (1997) |

|

Social |

Williams (2001) |

|

Shared mental models |

Multi-component |

Crossan, Lane & White (1999) |

Integrated |

Jenkin (2013); Kim (1993); Lewis (2014) |

|

Action learning/cyclical |

Murray (2002) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Nonaka (1994) |

|

Socio-cognitive |

Cho et al. (2013) |

|

Cognitive |

Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier (1997) |

|

Social |

Williams (2001) |

|

Shared vision |

Multi-component |

Babaeinesami & Ghasemi (2021); Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera (2005); Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002) |

Action learning/cyclical |

Law & Gunasekaran (2009); Murray (2002) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Nonaka (1994) |

|

Socio-cognitive |

Cho et al. (2013) |

|

Cognitive |

Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier (1997) |

|

Social |

Williams (2001) |

|

Collaboration |

Multi-component |

Babaeinesami & Ghasemi (2021); Edwards (2017); Mulholland et al. (2000) |

Integrated |

Lawrence et al. (2005); Kaur & Hirudayaraj (2021) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Nonaka (1994) |

|

Cognitive |

Provera, Montefusco & Canato (2010) |

|

Social |

Williams (2001) |

|

Psychological safety |

Multi-component |

Chen (2005); Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002) |

Cognitive |

Provera, Montefusco & Canato (2010) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Duffield & Whitty (2016) |

|

Socio-cognitive |

Argote & Miron-Spektor (2011) |

|

Communities of practice |

Multi-component |

Crossan, Lane & White (1999); Mulholland et al. (2000) |

Integrated |

Lawrence et al. (2005) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Duffield & Whitty (2016); Malone (2002); Nonaka (1994) |

|

Leadership |

Multi-component |

Babaeinesami & Ghasemi (2021); Chou & Ramser (2019); Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera (2005); Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002) |

Integrated |

Kaur & Hirudayaraj (2021) |

|

Action learning/cyclical |

Law & Gunasekaran (2009) |

|

Organisational systems |

Multi-component |

Crossan, Lane & White (1999); Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002) |

Integrated |

Lawrence et al. (2005) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Duffield & Whitty (2016); Malone (2002) |

|

Cognitive |

Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier (1997) |

|

Reflection |

Multi-component |

Chen (2005); Mulholland et al. (2000) |

Integrated |

Kaur & Hirudayaraj (2021) |

|

Action learning/cyclical |

Schumacher (2015) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Nonaka (1994) |

|

Learning culture |

Multi-component |

Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002) |

Action learning/cyclical |

Law & Gunasekaran (2009) |

|

Knowledge-focused |

Duffield & Whitty (2016) |

|

Socio-cognitive |

Cho et al. (2013) |

|

Cognitive |

Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier (1997) |

|

Social |

Williams (2001) |

|

Feed forward/ feedback |

Multi-component |

Crossan, Lane & White (1999) |

Integrated |

Jenkin (2013); Lawrence et al. (2005); Zietsma et al. (2002) |

|

Learning from errors |

Multi-component |

Edwards (2017); Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002) |

Knowledge-focused |

Duffield & Whitty (2016) |

|

Cognitive |

Provera, Montefusco & Canato (2010) |

|

Team learning |

Multi-component |

Babaeinesami & Ghasemi (2021); Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera (2005) |

Socio-cognitive |

Akgün, Lynn & Byrne (2003) |

|

Problem solving |

Multi-component |

Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman (2002) |

Action learning/cyclical |

Schumacher (2015) |

In summary, seven different OL models, frameworks or approaches, and 14 key enablers of OL were found in the literature in response to the review’s two guiding questions. The following discussion seeks to synthesise these models, frameworks and/or approaches and their enablers into a standardised approach to OL for uplifting of workforce capability.

DISCUSSION

WORKING DEFINITIONS OF MODELS, FRAMEWORKS AND/OR APPROACHES

Socio-cognitive, action learning, cyclical, cognitive, no-blame and social models, frameworks or approaches are well defined in the OL literature (see for example Bandura 1977; Easterby-Smith 1997; Fiol & Lyles 1985; Huber 1991; Lewin 1946). In addition to these models, frameworks or approaches, some are also grouped in this review as either multi-level, integrated or knowledge-focused. By way of explanation, any model, framework or approach categorised as ‘multi-component’ refers to those describing multiple systems, facets, levels, dimensions or modes to OL. For example, the often-cited 4I model, by Crossan, Lane and White (1999), depicts OL as four related sub-processes: intuiting, interpreting, integrating and institutionalising, that occur over three levels: individual, group and organisational. Lipshitz, Popper and Friedman (2002) propose contextual, structural, cultural, psychological and policy facets to their OL conceptual model, while Chou and Ramser (2019) suggest a multi-level, bottom-up perspective of OL as opposed to a single-level, top-down and organised event initiated by the leader.

‘Integrated’ models, frameworks or approaches are those that combine or build on different theories or constructs. For example, Lawrence et al. (2005) build on the 4I model (Crossan, Lane & White 1999) by adding dimensions of power and politics to OL. Zietsma et al. (2002) also extend the 4I model by adding two action-learning processes –attending and experimenting, while Kaur and Hirudayaraj (2021) add an emotional intelligence component to the 4I model. Another frequently cited model is Kim’s (1993) OADI-SMM model, which integrates an individual’s learning processes of observing, assessing, designing and implementing (OADI), with the transfer of the ensuing knowledge to the organisation, i.e., a shared mental model (SMM).

Any OL model, framework or approach grouped in the ‘knowledge- focused’ category makes explicit reference to knowledge as the most critical resource in an organisation, often referring to information generation, interpretation, storage and dissemination. For example, the widely cited socialisation, externalisation, combination, internalisation (SECI) model by Nonaka (1994) views organisations as dynamic knowledge- creation entities, where there are two-way conversions between tacit knowledge (i.e., the highly personalised, difficult to communicate ‘know-how’) and explicit knowledge (i.e., knowledge that is codified and readily transferrable). Malone’s (2002) model is premised on knowledge management, and the ways in which organisations capture and disseminate information.

THE COMMON GROUND

Since OL literature draws upon multiple disciplines (psychology, sociology, management, organisation science) it is difficult to synthesise the results into a single, standardised approach (Easterby-Smith 1997; Williams 2001). The reviewed literature found commonalities among the different models, frameworks and approaches. For example, Crossan, Lane and White’s (1999) multi-component 4I model requires some cognitive and socio-cognitive activity across all four processes of intuiting, interpreting, integrating and institutionalising, and there are socio-cognitive and social aspects in the contextual, structural, cultural, psychological and policy facets of Lipshitz, Popper and Friedman’s (2002) multi-component model. Nonaka’s (1994) knowledge-focused SECI model requires cognition and socialisation, as does the cyclical model of Murray (2002) and action-learning model of Schumacher (2015). The Zietsma et al. (2002) integrated model incorporates two action-learning processes, and so on. Consequently, it would be reasonable to suggest that all OL models, frameworks and/ or approaches found within the literature are appropriate. What may be more helpful, when considering the best approach to OL, are the commonalities in the key enablers found across all models, frameworks and/or approaches. For ease of reference, Table 3 provides a snapshot of key enablers outlined in Table 2.

Table 3: Snapshot of key enablers across OL models, frameworks and/or approaches

| Key Enabler of OL | Multi-component | Integrated | Action Learning or Cyclical | Knowledge-focused | Socio-cognitive | Cognitive | Social |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge-management activities |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Shared mental models |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Shared vision |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Collaboration |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Psychological safety |  |

|

|

|

|||

| Communities of practice |  |

|

|

||||

| Leadership |  |

|

|

||||

| Organisational systems |  |

|

|

|

|||

| Reflection |  |

|

|

|

|||

| Learning culture |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Feed forward / feedback |  |

|

|||||

| Learning from errors |  |

|

|

||||

| Team learning |  |

|

|

||||

| Problem solving |  |

|

All 14 key enablers were found within every multi-component OL model framework and/or approach cited in Table 1 (Table 3), which again supports the complexity of OL and the difficulties in proposing a one-size-fits-all approach. Also, emerging from both Tables 2 and 3 are categories of key enablers, which may be helpful for uplifting workforce capability in healthcare organisations. These categories may be considered at the individual, group and organisational level (Chou & Ramser 2013; Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2000), with some enablers (e.g., reflection), having potential to span all three (e.g., Mulholland et al. 2000; Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010).

INDIVIDUAL ENABLERS

Kim (1993) states that the importance of individual learning to OL is both ‘…obvious and subtle –obvious because all organisations are composed of individuals; subtle because organisations can learn independent of any specific individual but not independent of all individuals’ (p. 37). Many theorists have articulated explanations of individual learning (e.g., Argyris & Schön 1978; Kolb 1984; Lewin 1946; Piaget 1970, all sources cited in Kim 1993) which are beyond the scope of this review. Three individual enablers of OL that emerge from the reviewed literature, are learning from errors, individual reflection, and mental model formation/sharing as a knowledge- management activity.

LEARNING FROM ERRORS

Noteworthy across many of the models, frameworks or approaches are the frequent references to theorists Argyris and Schön (1978). Seventeen of the 26 publications reviewed either make brief mention, or provide more detailed explanations, of single and double-loop learning (Argyris & Schön 1978). Single loop learning is described as a simple error detection and correction process. When something goes wrong, individuals may reflexively look for another strategy that will address and work within the governing variables. In other words, goals, values, plans and rules are operationalised rather than questioned (Argyris & Schön 1978). OL is better supported through double-loop learning, where errors are corrected through questioning or changing the organisation’s governing values, policies and objectives (e.g., Babaeinesami & Ghasemi 2021; Edwards 2017; Mulholland et al. 2000). Consequently, supporting people to think more deeply about and reflect upon their own assumptions and beliefs, and reconsider their strategies, is an important part of OL (Williams 2001).

REFLECTION

The multi-component ENRICH model of OL proposed by Mulholland et al. (2000) begins with an overview of individual learning. They base their theory on Schön’s (1983) theory of ‘reflection-in-action’. With this kind of reflection, individuals use and apply a range of knowledge and skills during the course of their work (i.e., knowledge-in-action). When a problem arises or an unexpected outcome occurs, the individual is required to reframe their problem, reflecting on their actions, questioning their assumptions and altering their activity. Once the problem has been resolved, the individual can return to their knowledge-in-action (Mulholland et al. 2000). Reflection-in-action highlights distinctions between tacit and explicit knowledge used within an organisation (Mulholland et al. 2000). Individuals may use their intuition and experience (i.e., tacit knowledge) to carry out their routine work, however when a problem arises, they must ‘reflect-in- action’ to bring their explicit knowledge into play (Mulholland et al. 2000). As an enabler at the individual level, reflection-in-action is positioned somewhere on the boundary between tacit and explicit knowledge (Mulholland et al. 2000). Supporting individuals to share their reflections and tacit knowledge may enhance OL (Williams 2001).

MENTAL MODELS

Reflection and learning from errors may also support individuals to form mental models or cognitive maps –internal images, ideas, memories and experiences that help us to make sense of and successfully interact with a complex world (Crossan, Lane & White 1999; Kim 1993; Williams 2001). For OL to occur, these mental models need to be made explicit and shared with the organisation (Kim 1993). As ‘the prime movers in the process of organizational knowledge creation’ (Nonaka 1994, p. 17), individuals require intentionality, an action-orientated concept where they make sense of the world and form their approach; a sense of autonomy which will motivate them to form new knowledge; and a degree of fluctuation, determined by their interaction with a dynamic external environment (Nonaka 1994). Once committed to OL, individuals may then participate in converting knowledge from tacit to explicit (Nonaka 1994). In the 4I model, these processes align with the first two phases –intuiting and interpreting (Crossan, Lane & White 1999). A ‘feed-forward’ process is also supported, shifting the individual learning to learning among individuals or groups (Crossan, Lane & White 1999; Zietsma et al. 2002).

FEELING PSYCHOLOGICALLY SAFE

Psychological safety facilitates and enables reflection and other knowledge-management activities such as mental models and the feed- forward process (Chen 2005; Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). It allows individuals to be comfortable to make mistakes, and openly and honestly discuss what they think and feel. Psychological safety makes it easier to face the potentially disturbing or embarrassing outcomes of inquiry, and to care for and share knowledge with others (Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). Chen (2005) cites as an example a long-established print and digital document company where maintenance workers are encouraged to keep personal diaries of major issues encountered during the course of their work, which are then shared through a corporate-wide intranet. This sharing of individual knowledge and experience enables others to solve similar problems (Chen 2005; Duffield & Whitty 2016). Pilots, too, are encouraged to share their individual flight experiences in conversations as part of an OL learning process (Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010). In healthcare organisations, however, clinicians may be unwilling to share information about errors for fear of legal repercussions (Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010). In these settings, effective team building along with interpersonal relations of trust and respect are important for enhancing psychological safety (Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010).

In summary, effective OL requires organisations to support individuals to think more deeply about their beliefs, challenge their assumptions and review and improve their ways of working, encouraging them to share their reflections and tacit knowledge in an environment that is psychologically safe and free from defensive routines (Argote & Miron-Spektor 2011).

GROUP ENABLERS

Developing OL is not as simple as combining the individual learning of each of the organisation’s members (Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle- Cabrera 2005; Law & Gunasekaran 2009). Group enablers are needed, that is, social activities that help individuals to communicate their mental models to create a common language, shared meaning, and an agreed course of action (Crossan, Lane & White 1999). Group enablers, such as collaboration, knowledge-management activities, shared mental models, shared vision, communities of practice, group reflection, feed forward/ feedback mechanisms, learning from errors, team learning and problem solving, were found in the reviewed literature, although there appeared to be some similarity among these (e.g., shared vision, shared mental models, collaboration). Therefore, we have chosen to focus only on shared vision and communities of practice as group enablers of OL in this section. Although found to be a standalone model in the OL literature, we noted that features of action learning (e.g., the action-learning set) were also mentioned as a process for facilitating OL (Law & Gunasekaran; 2009; Schumacher 2015) and as such, action learning is also discussed here.

SHARED VISION

While the concept of OL infers shared knowledge, perceptions and beliefs (Williams 2001), along with problem solving (Schumacher 2015) and collaboration (Edwards 2017), OL will be enhanced by a common language and joint action by all individuals involved in the process, that is, a shared vision (Kim 1993; Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera 2005). As an organisation’s ‘collective conscience’, shared vision helps groups to focus, and provides direction for what should be learned (Cho et al. 2013; Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera 2005; Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier 1997).

Murray (2002) suggests that managers can foster shared vision through encouraging individuals to communicate their personal vision, by communicating and asking for support, and by considering ‘vision’ as an ongoing process that combines both extrinsic and intrinsic visions. Shared vision may also enable groups and organisations to accept and try new ideas through critical evaluation of past practices (Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier 1997). Such an approach requires values of transparency, accountability, an orientation to organisational issues, openness and trust (Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). These values may be key in determining the success of OL group enablers, such as communities of practice and action-learning sets.

COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

Communities of practice are groups of people who engage in a process of collected learning in a shared domain of human endeavour, for example, a tribe learning to survive, an online discussion forum, workers on a factory floor, scientists in a laboratory (Lave & Wenger 1991), each with a particular set of norms and practices (Gherardi 2009). It is through the process of sharing information and experiences with the group that the members learn from each other and have an opportunity to develop and continually evolve, both personally and professionally (Lave & Wenger 1991).

Malone (2002) distinguishes between knowledge communities and communities of practice, suggesting that the former are those established by an organisation after identifying likely areas of interest, while communities of practice are allowed to form organically. In either case, these communities typically do not have a set agenda or well-defined goals, other than to expand thinking along common areas of interest. Lunchbox talks, online chat groups, storytelling forums, team meetings, technical exchange groups and special interest groups are suggested as ways for organisations to support learning through coherent, collective action (Duffield & Whitty 2016). As Malone (2002) points out, any strategy that shifts the focus from documents to discussion is a good way to facilitate exchange of information.

Storytelling is a significant part of OL within a community of practice, as stories represent the complexity of practice more accurately than what may be taught in more formal educational settings (Crossan, Lane & White,1999; Duffield & Whitty 2016). Mulholland et al. (2000) cite Orr’s (1990) famous account of Xerox engineers sharing ‘war stories’ about problems encountered with different kinds of photocopier machines and how they were managed. Discussion of work-related issues as they gathered around water coolers, during lunch breaks or at social meetings easily led to a shared understanding and creation of new knowledge. The stories themselves, although an unofficial learning resource and not part of any kind of organisational manual, became the repository of wisdom, and a way of converting tacit to explicit knowledge (Crossan, Lane & White 1999; Duffield & Whitty 2016; Mulholland et al. 2000).

ACTION LEARNING

In addition to consideration as a model, framework or approach for OL, the processes within an action-learning group or set may also comprise an OL enabler. Core assumptions underpinning action learning are that formal instruction and theory is not sufficient, and external training or expertise cannot be relied upon as it may not suit the particular context of a problem (Schumacher 2015). Schumacher (2015) cites the key work of Revans (1982), in claiming that OL is effective when group members, as ‘comrades in adversity’, constructively work on real-time problems by asking questions, developing hypotheses, reflecting on the challenge, and sharing knowledge, practices and personal views, and when this is followed by a debriefing (Schumacher 2015). The informal structures and processes associated with action learning suggest that action-learning groups may be formed organically, like communities of practice. Although, similar to knowledge communities, they may also be more formally convened.

Much of the action literature describes intra-organisational action- learning sets, yet inter-organisational action learning is becoming increasingly important (Schumacher 2015). As an example, Schumacher (2015) cites an early project of Revans (1972) where ten London hospitals participated in action learning, offering networking opportunities, fostering strong links between organisations and connecting different contexts and projects. This inter-organisational action learning may be relevant to today’s healthcare organisations, with their diverse teams, portfolios and departments. In these action-learning sets, participants are initially familiarised with the different contexts of each team, portfolio or department, before exchanging good practices within a shared area of interest while working on common work-related problems, concerns or opportunities (Schumacher 2015). Where action learners are drawn from across an organisation, learning can benefit both individuals and the organisation (Schumacher 2015).

In summary, group enablers are important for effective OL. Communities of practice and action-learning sets, where social activities such as journalling, storytelling and other informal or semi-formal conversations help to create and support a shared understanding (Crossan, Lane & White 1999; Duffield & Whitty 2016; Malone 2002; Mulholland et al. 2000; Schumacher 2015) are considered important group enablers. The success of these enablers for OL is underpinned by a third enabler-shared vision, a ‘collective conscience’ fostered by the organisation, which provides direction and helps groups to focus their learning (Cho et al. 2013; Jerez- Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera 2005; Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier 1997).

ORGANISATIONAL ENABLERS

The reviewed literature emphasises the importance of fostering a learning culture to facilitate knowledge transfer across all levels of the organisation (e.g., Cho et al. 2013; Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera 2005; Law & Gunasekaran 2009; Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier 1997), although a unified definition of such a culture is elusive. In addition to the individual and group enablers already discussed, effective organisational systems and procedures, supported by strong leadership and management, emerged from the literature as OL enablers and are also considered to underpin a learning culture.

SYSTEMS AND PROCEDURES

Effective OL requires roles, functions and procedures to guide the systematic collection, analysis, storage, dissemination and usage of information, that is, organisational learning mechanisms (Kim 1993; Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). Such mechanisms include forms and checklists, guidelines (Duffield & Whitty 2016), post-project or post-incident reviews, routine performance reviews, strategic planning, auditing and quality improvement or quality control procedures (Lipschitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). Standard operating procedures or protocols are also noted as enablers of OL, although there are concerns around their rigidity and lack of room for error, necessitating processes for workarounds and self- correction if errors are made (Kim 1993; Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010).

Systems for knowledge management, such as the internet, intranet, dashboards, repositories and databases to facilitate digital exchange (i.e., knowledge networks) are important enablers for OL (Malone 2002). Other non-technical strategies for knowledge exchange, including newsletters, interoffice communications, white papers, professional publications, office libraries and even data archives may also be considered to be effective knowledge networks (Malone 2002).

Systems and processes for effective OL should be carefully and strategically managed (Malone 2002). Complex, rigid or unreliable systems that are implemented without effective support or consideration of the end users have the potential to inhibit rather than enable OL, driving out innovation and hindering professional autonomy (Carroll & Edmondson 2002; Duffield & Whitty 2016). Crossan, Lane and White (1999) also warn that learning that has been formalised or institutionalised may not always fit the context, as organisational environments are constantly changing. As a result, the systems and processes need not always be overly prescriptive (telling someone how to perform their role) (Carroll & Edmondson 2002), but instead should encourage individuals and groups to feed forward any new learning, and find ways to integrate this with what is already embedded in existing systems and procedures, the feed forward/feedback approach (Crossan, Lane & White 1999).

Although learning from errors is discussed at the individual level, health care systems (i.e., the organisational level) are renowned for their no- blame cultures (Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010). As high-reliability organisations, hospitals experience long periods of safety, remaining ‘invisible’ until an error threatens to unravel their systems (Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010). A no-blame approach, with systematic analyses, debriefings, and narratives where individuals and groups are able to share their experiences in a supportive environment, may enhance learning and also discourage staff from taking ‘shortcuts’, change the attitudes of staff who may be resigned about errors, and prevent feelings of invincibility (Argote & Miron-Spektor 2011; Chen 2005; Provera, Montefusco & Canato 2010).

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT

In hierarchical organisations, senior managers may have the most influence over OL; therefore, managerial commitment to a learning culture where knowledge acquisition, creation and transfer are core values, is fundamental to effective OL (Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle- Cabrera 2005; Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier 1997; Williams 2001). Evidence of this commitment may be found in managers that articulate a vision and mission for implementing OL, championing learning as a valuable tool for organisational success (Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes-Lorente & Valle-Cabrera 2005; Law & Gunasekaran 2009). Law and Gunasekaran (2009) cite two examples of successful OL in motor companies who, through high-level managerial commitment to learning infrastructure, shared vision, team building and coordinated, integrated learning tasks, were able to turn huge financial losses into substantial profits. From a healthcare organisation perspective, a study of lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic across ten Italian intensive-care units found that leadership styles that supported OL through collaboration, teamwork and open communication were able to transform and improve their operations beyond the initial health care emergency (Gambirasio et al. 2023).

Managerial commitment to OL does not necessarily need to be hierarchical or occur at the executive level. Chou and Ramser (2019) state that leaders (not necessarily ‘managers’) at all organisational levels are essential for effective OL. The most prominent leadership style emerging from the reviewed literature that promotes effective OL is transformational leadership. Other styles, such as charismatic leadership or humanistic leadership that focus on mutual stimulation, empathy, teamwork and inclusivity, are also important (Chou & Ramser 2019; Kaur & Hirudayaraj 2021). Besides these leadership styles, Chou and Ramser (2019) advocate for a leader-member exchange (LMX) approach that inspires staff to spontaneously assist their leaders with tasks (upward helping) and openly express their opinions and suggestions (voice behaviour) (Chou & Ramser 2019). This approach supports OL through the development of human and social capital –leaders gain a better understanding of, and are able to respond to staff learning needs, while at the same time improving their own knowledge and skills (Chou & Ramser 2019).

Regardless of leadership style, an OL culture is enhanced by leaders’ emotional intelligence and the emotional competencies of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and relationship management (Kaur & Hirudayaraj 2021). For example, self-awareness and self-management may assist leaders to manage any negative emotions that might impede the OL process, while social-awareness skills, such as empathy and service-orientation, assist leaders to recognise and accommodate the individual needs of their team members (Kaur & Hirudayaraj 2021). These competencies, along with relationship management, support a psychologically safe environment that encourages individuals and teams to experiment, create and exchange ideas (Kaur & Hirudayaraj 2021). An emotionally intelligent leader may also then facilitate the formalisation of knowledge into systems and procedures (Kaur & Hirudayaraj 2021).

The principal focus on leadership and management for effective OL seems to be in relation to social and psychological attributes, and yet there are also political and power dimensions (Lawrence et al. 2005). Lawrence et al. (2005) outline four propositions that they consider to be missing from OL literature. Firstly, they argue that interpretation of new ideas and subsequent learning is best facilitated by the use of influence as a means of overcoming ambiguity and uncertainty associated with OL. Second, some formal authority is required to ‘force’ the accomplishment of collective action. Third, systems of domination (i.e., rules and restrictions) are required to overcome potential resistance to change, and finally, effective OL requires consistency and discipline to support the development of expertise (Lawrence et al. 2005). These political and power aspects to OL are not considered dysfunctional or in need of correction, but rather, are inherent in the OL process and if appreciated and understood, can by leveraged by organisations to support effective OL (Lawrence et al. 2005).

One practical application that may help manage organisational power and politics is the role of a ‘champion’ in OL. Lawrence et al. (2005) propose champions with varying skills and resources to negotiate the different phases of OL, specifically the phases of intuiting, interpreting, integrating and institutionalising in the 4I model by Crossan, Lane and White (1999). In addition to the usual ‘innovation champions’, they suggest that champions with skills to influence the adoption of ideas, champions with the authority to ensure that ideas are enacted, and champions who can design and implement systems to support their enactment may leverage power and politics and contribute to successful OL (Lawrence et al. 2005).

Consideration of leadership and management as enablers of OL has implications for education and training, and human resource development in healthcare organisations. Soft-skills training interventions, such as communication and interpersonal skills, teamwork and problem solving, are valuable inclusions in leadership development and coaching programs, as are consideration of these skills when making staff recruitment decisions (Chou & Ramser 2019; Kaur & Hirudayaraj 2021).

SUMMARY OF ENABLERS

In summary, OL enablers may be seen across three levels: individual, group and organisational. The preceding discussion does not include all enablers identified in the literature or all enablers proposed by key theorists, but instead presents some of the stronger emerging themes that may inform strategies for uplifting workforce capability in healthcare organisations. Table 4 provides a brief premise for each enabler that has been considered.

Table 4: Enablers and premises

Level |

Enabler |

Premise |

Individual |

Learning from errors |

OL is best supported through double-loop learning where errors are detected and then corrected through questioning or changing the organisation’s governing values, policies and objectives (Argyris & Schön 1978). |

Reflection |

Platforms for the sharing of individual reflections may facilitate the conversion of tacit to explicit knowledge (Mulholland et al. 2000; Williams 2001). |

|

Mental models |

Internal images, ideas, memories and experiences that help to make sense of and successfully interact with the external environment. OL is enhanced when individuals are supported to share their mental models, i.e., make their tacit knowledge explicit (Crossan, Lane & White,1999; Kim 1993; Williams 2001). |

|

Psychological safety |

OL is enhanced in an environment where individuals are comfortable to make mistakes, and are supported to discuss openly and honestly what they think and feel, and share knowledge with others (Chen 2005; Duffield & Whitty 2016; Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). |

|

Group |

Shared vision |

As an organisation’s ‘collective conscience’, making a shared vision explicit and adopting it helps groups to focus, and provides direction for what should be learned (Cho et al. 2013; Jerez-Go̒mez, Cespedes- Lorente & Valle-Cabrera 2005; Sinkula, Baker & Noordewier 1997). |

Communities of practice |

Lunchbox talks, online chat groups, storytelling forums, team meetings, technical exchange groups and special interest groups are ways for organisations to support learning through coherent, collective action (Duffield & Whitty 2016). Communities of practice usually form organically, while knowledge communities are often arranged (Malone 2002). |

|

Action learning |

OL is effective when group members work constructively on real-time problems by asking questions, developing hypotheses, reflecting on the challenge, sharing knowledge, practices and personal views, followed by a debriefing (Schumacher 2015). |

|

Organisational |

Systems and procedures |

Effective OL requires roles, functions and procedures to guide the systematic collection, analysis, storage, dissemination and usage of information (Kim 1993; Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). Suggestions include forms, checklists and guidelines (Duffield & Whitty 2016), post-project or post-incident reviews, performance reviews, strategic planning, auditing and quality improvement activities (Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002). A combination of digital and non-digital strategies is recommended (Malone 2002). Systems and procedures should be reviewed regularly based on feed forward (from individuals and groups) and feedback (from the organisation) mechanisms (Crossan, Lane & White 1999). |

Leadership and management |

Managerial commitment at the executive level, and leadership throughout the various levels supports effective OL. Leadership and management development programs that facilitate human-centred leadership approaches are important for OL (Chou & Ramser 2019; Kaur & Hirudayaraj 2021). |

LIMITATIONS OF THE REVIEW

A comprehensive literature review was undertaken, however due to the plethora of OL publications, along with the fact that many papers used the terms ‘organisational learning’ and ‘learning organisation’ interchangeably, relevant material may have been excluded. Moreover, while the OL literature has developed over many years, it remains dominated by persuasive and/or analytical papers, rather than studies focusing on theory development (Easterby-Smith 1997). Establishing a definitive model, framework or approach is challenging. The concept of OL still lacks a theoretical basis and does not provide hands-on knowledge for practitioners (Lipshitz, Popper & Friedman 2002) –those seeking to enact OL models. Therefore, a future direction should be to develop a theoretical basis or underpinning for OL.

The review is also open to biases inherent in the heterogenous nature of the literature and the absence of an appraisal tool. These biases were addressed through the inclusion of a large number of publications (n = 26), ensuring as wide a coverage as practicable. The use of a systematic screening and reporting process may also have mitigated these limitations.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In summary, seven different OL models, frameworks and/or approaches were identified in the reviewed literature. There was considerable overlap, rendering it difficult to synthesise the findings into a standardised approach. Although multi-level or integrated approaches were the most widely cited, these approaches did not draw from a single discipline. Cognitive, social, socio-cognitive, socio-cultural, action learning, organisational and management development learning theories were found in various combinations across the publications.

No single OL model, framework and/or approach is endorsed. OL is a complex, multi-dimensional construct, involving dynamic processes and interactions between individuals and their surrounding environments. For maximum impact of OL, and to ensure a continuous learning process in an organisation, models, frameworks and/or approaches need to consider multiple dimensions, facets and levels.

While a standardised approach could not be identified due to this complexity, consideration of the multiple sub-processes that contribute to OL appeared to be less difficult. The reviewed literature revealed 14 enablers across the individual, group and organisational levels. Considering the premise of each enabler discussed in this review, five recommendations are proposed for supporting OL in the healthcare context. Firstly, organisations should articulate a vision or shared purpose that is clearly communicated and embedded across all of their departments, teams and activities. Secondly, as high-risk organisations, there should be a genuine commitment to a no-blame culture and the creation of a psychologically safe environment within healthcare organisations. Third, systems and procedures that provide clear guidelines for safety and quality, while still encouraging innovation and supporting role autonomy, are important. Fourth, healthcare organisations should consider recruitment and/or development of leaders and managers across all levels with exemplary soft skills such as communication and interpersonal skills, teamwork and problem solving. Finally, seeking ways for individuals to convert their tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge and share it with others, such as reflection, communities of practice or knowledge communities, and action learning, may support effective OL in healthcare organisations.

Productive OL is difficult to achieve. OL appears not as a single approach enacted by an entire organisation in a standard fashion, but instead as a series of loosely linked enablers in which different departments, teams or portfolios will participate in different ways and with varying degrees of intensity. Regular appraisal of the effectiveness of these enablers across organisational areas and levels will assist in determining the extent and quality of OL.

References

Akgün, AE, Lynn, GS & Byrne, JC 2003, ‘Organizational learning: A socio- cognitive framework’, Human Relations, vol. 56, no. 7, pp. 839–68.

Alerasoul, SA, Afeltra, G, Hakala, H, Minelli, E & Strozzi, F 2022, ‘Organisational learning, learning organisation, and learning orientation: An integrative review and framework’, Human Resource Management Review , vol. 32, no. 3, p. 100854.

Arksey, H & O’Malley, L 2005, ‘Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology , vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 19–32.

Argote, L & Miron-Spektor, E 2011, ‘Organizational learning: from experience to knowledge’, Organization Science, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 1123–37.

Argyris, C & Schön, D 1978, Organizational learning: a theory of action perspective . Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) 2019, The state of patient safety and quality in Australian hospitals 2019 , ACSQHC, Sydney.

Babaeinesami, A & Ghasemi, P 2021, ‘Ranking of hospitals: a new approach comparing organizational learning criteria’, International Journal of Healthcare Management , vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 1031–9.

Bandura, A 1977, Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Basten, D & Haamann, T 2018, ‘Approaches for organizational learning: a literature review’, Sage Open, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 2158244018794224.

Carroll, JS & Edmondson, AC 2002, ‘Leading organisational learning in health care’, BMJ Quality & Safety, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 51–6.

Chen, G 2005, ‘An organizational learning model based on western and Chinese management thoughts and practices’, Management Decision , vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 479–500.

Cho, I, Kim, JK, Park, H & Cho, NH 2013, ‘The relationship between organisational culture and service quality through organisational learning framework’, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence , vol. 24, no. 7–8, pp. 753–768.

Chou, SY & Ramser, C 2019, ‘A multilevel model of organizational learning: incorporating employee spontaneous workplace behaviors, leadership capital and knowledge management’, The Learning Organization , vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 132–45.

Colquhoun, HL, Levac, D, O’Brien, KK, Straus, S, Tricco, AC, Perrier, L, Kastner, M & Moher, D 2014, ‘Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting’, Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , vol. 67, no. 12, pp. 1291–4, viewed 15 May 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 .

Crossan, MM, Lane, HW & White, RE 1999, ‘An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution’, Academy of Management Review , vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 522–37.

Doyle, L, Kelliher, F & Harrington, D 2021, ‘Multi-level learning in public healthcare medical teams: the role of the social environment’, Journal of Health Organization and Management, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 88–105.

Duffield, SM & Whitty, SJ 2016, ‘Application of the systemic lessons learned knowledge model for organisational learning through projects’, International Journal of Project Management, vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 1280–93.

Easterby-Smith M 1997, ‘Disciplines of organizational learning: contributions and critiques’, Human Relations, vol. 50, no. 9, pp. 1085–113.

Easterby-Smith M & Lyles, MA eds. 2011, Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management . Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Edwards, MT 2017, ‘An organizational learning framework for patient safety’,

American Journal of Medical Quality, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 148–55.

Fiol, CM & Lyles, MA 1985, ‘Organizational Learning’, Academy of Management Review , vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 803–813.

Gambirasio, M, Magatti, D, Barbetta, V, Brena, S, Lizzola, G, Pandolfini, C, et al. 2023, ‘Organizational Learning in Healthcare Contexts after COVID-19: A Study of 10 Intensive Care Units in Central and Northern Italy through Framework Analysis’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , vol. 20, no. 17, p. 6699.

Gherardi, S 2009, ‘Community of practice or practices of a community?’, in Armstrong S & Fukami C eds., The Sage handbook of management learning, education, and development . London: Sage, pp. 514–530.

Hsu, C & Pereira, A 2008, ‘Internationalization and performance: The moderating effects of organizational learning’, Omega, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 188–205.

Huber, GP 1991, ‘Organizational learning: the contributing processes and the literatures’, Organization Science, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 88–115.

Jenkin, TA 2013, ‘Extending the 4I organizational learning model: information sources, foraging processes and tools’, Administrative Sciences , vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 96–109.

Jerez-Gómez, P, Céspedes-Lorente, J & Valle-Cabrera, R 2005, ‘Organizational learning capability: a proposal of measurement’, Journal of Business Research , vol. 58, no. 6, pp. 715–25.

Kaur, N & Hirudayaraj, M 2021, ‘The role of leader emotional intelligence in organizational learning: A literature review using 4I framework’, New

Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, vol. 33, no. 1,

pp. 51–68.

Kim, DH 1993, ‘The link between individual and organizational learning’,

Sloan Management Review, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 37–50.

Lave, J & Wenger, E 1991, Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Law, KM & Gunasekaran, A 2009, ‘Dynamic organizational learning: a conceptual framework’, Industrial and Commercial Training, vol. 41, no. 6,

pp. 314–20.

Lawrence, TB, Mauws, MK, Dyck, B & Kleysen, RF 2005, ‘The politics of organizational learning: Integrating power into the 4I framework’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 180–91.

Lewin, K 1946, ‘Action learning and minority problems’, Journal of Social Issues , vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 34–46.

Lewis, J 2014, ‘ADIIEA: An organizational learning model for business management and innovation’, Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management , vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 98–107.

Lipshitz, R, Popper, M & Friedman, VJ 2002, ‘A multifacet model of organizational learning’, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 78–98.

Malone, D 2002, ‘Knowledge management: A model for organizational learning’, International Journal of Accounting Information Systems , vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 111–23.

Ministry of Health NSW 2022, NSW Health Workforce Plan 2022–2032 . [online] June. Available at: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/ .

Mulholland, P, Domingue, J, Zdrahal, Z & Hatala, M 2000, ‘Supporting organisational learning: an overview of the ENRICH approach’, Information Services & Use, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 9–23.

Munn, Z, Peters, MD, Stern, C, Tufanaru, C, McArthur, A & Aromataris, E 2018, ‘Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach’, BMC Medical Research Methodology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–7.

Murray, P 2002, ‘Cycles of organisational learning: a conceptual approach’, Management Decision, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 439–47.

Nonaka, I 1994, ‘A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation’, Organization Science, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 14–37.

Örtenblad, A 2001, ‘On differences between organizational learning and learning organization’, The Learning Organization, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 125–33.

Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. 2021, ‘The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews’, BMJ, vol. 372, p. n71, viewed 15 May 2025, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 .

Provera, B, Montefusco, A & Canato, A 2010, ‘A ‘no blame’ approach to organizational learning’, British Journal of Management, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1057–74.

Schilling, J & Kluge, A 2009, ‘Barriers to organizational learning: An integration of theory and research’, International Journal of Management Reviews , vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 337–60.

Schön, DA 1983, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action . New York: Basic Books.

Schumacher, T 2015, ‘Linking action learning and inter-organisational learning: The learning journey approach’, Action Learning: Research and Practice , vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 293–313.

Sinkula, JM, Baker, WE & Noordewier, T 1997, ‘A framework for market- based organizational learning: linking values, knowledge, and behavior’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 305–18.

Sun, H 2003, ‘Conceptual clarifications for ‘organizational learning’, ‘learning organization’ and ‘a learning organization’’, Human Resource Development International , vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 153–166.

Tsang, EWK 1997, ‘Organizational learning and the learning organization: a dichotomy between descriptive and prescriptive research’, Human Relations, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 73–89.

Williams, AP 2001, ‘A belief-focused process model of organizational learning’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 67–85.

Zhao, J, Wang, M, Zhu, L & Ding, J 2014, ‘Corporate social capital and business model innovation: the mediating role of organizational learning’, Frontiers of Business Research in China, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 500–28.

Zietsma, C, Winn, M, Branzei, O & Vertinsky, I, 2002 ‘The war of the woods: Facilitators and impediments of organizational learning processes’, British Journal of Management, vol. 13, no. S2, pp. S61–S76.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL: INCLUDED LITERATURE

This supplementary material was part of the submitted manuscript and is presented as supplied by the authors.

Citation |

PublicationType |

Framework |

Overview |

Akgün, A. E., Lynn, G. S., & Byrne, J. C. (2003). Organizational learning: A socio-cognitive framework. Human relations, 56(7), 839-868. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Socio-cognitive |

OL is an outcome of reciprocal interactions of the processes of information/ knowledge acquisition, dissemination, implementation, sensemaking, memory, thinking, unlearning, intelligence improvisation and emotion –connected by organisational culture. Organisational culture links the socio-cognitive constructs and thereby mediates the OL process. |

Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E. (2011). Organizational Learning: From Experience to Knowledge. Organization Science 22(5), pp. 1123–1137. |

Persuasive/ discussion paper |

Socio-cognitive |

Organisational experience (e.g., about tasks, members, other organisational units) interacts with the context to create, retain and transfer knowledge. The context includes the environment (e.g., clients, institutions, regulators), and the organisational context, which is either active (members and tools capable of action) or latent (culture). Psychological safety, social network, identity, power differences and how interactions between members affect OL. |

Babaeinesami, A., & Ghasemi, P. (2021). Ranking of hospitals: a new approach comparing organizational learning criteria. International journal of healthcare management, 14(4), 1031-1039. |

Research paper |

Multi- dimensional |

Combines several models (Goh & Richards, 1997; Templeton et al. 2002) to arrive at a set of OL criteria to rank OL in five Iranian hospitals. Dimensions are: building the ability to learn, collaborative setting of missions and strategies, building the future together, awareness, communication, performance assessment, intellectual cultivation, environment adaptability, social learning, intellectual capital management, organisational grafting, leadership, experimentation, transfer of knowledge, teamwork and group problem solving. |

Chen, G. (2005). An organizational learning model based on western and Chinese management thoughts and practices. Management Decision , 43(4), 479-500. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Multi-system |

The model proposes an OL system model based on both western and Chinese management thoughts. Consists of nine interrelated OL sub-systems including “discovering”, “innovating”, “selecting”, “executing”, “transferring”, “reflecting”, “acquiring knowledge from environment”, “contributing knowledge to environment”, and “building organizational memory”. |

Cho, I., Kim, J. K., Park, H., & Cho, N. H. (2013). The relationship between organisational culture and service quality through organisational learning framework. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence , 24(7-8), 753-768. |

Research paper |

Socio-cognitive |

Proposes integration of Sinkula et al.’s (1997) cognitive framework with four types of organizational culture –group (i.e., frequent sharing and trust among group members), rational (i.e., provides clear goals to organisational members and regards ability and outcome as the most important factors for increasing job effectiveness), hierarchical (i.e., culture that works according to a structured procedure) developmental (i.e., an innovative and dynamic culture in which members do not fear new challenges). |

Chou, S. Y., & Ramser, C. (2019). A multilevel model of organizational learning: incorporating employee spontaneous workplace behaviors, leadership capital and knowledge management. The Learning Organization, 26(2), 132-145. |

Conceptual analysis paper |

Multi-level |

Grounded in transformational leadership theory, this paper suggests a multi- level, bottom-up perspective of OL as opposed to a single -level, top-down and organised event initiated by the leader. Proposes that an employee’s upward helping increases human and social capital; that the leader’s human and social capital enhance the employee’s psychological empowerment and knowledge leadership; that the employee’s psychological empowerment leads to employee voice behaviour (i.e., willingness to speak up), which then strengthens knowledge leadership and finally promotes OL. |

Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., & White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Academy of management review , 24(3), 522-537. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Multi-level: 4I Model |

Presents OL as four related sub-processes –Intuiting, Interpreting, Integrating and Institutionalising, that occur over three levels: individual, group and organisational. Intuiting is the preconscious recognition of the pattern and/ or possibilities inherent in a personal stream of experience; Interpreting is the explaining of an idea to oneself and to others; integrating is the process of developing shared understanding among individuals and then taking coordinated action; institutionalising is the process of ensuring that routines are enacted. Intuiting and interpreting occur at the individual level, interpreting and integrating occur at the group level, integrating and institutionalising occur at the organisation level. |

Duffield, S. M., & Whitty, S. J. (2016). Application of the systemic lessons learned knowledge model for organisational learning through projects. International journal of project management , 34(7), 1280-1293. |

Research paper |

Syllk |

The systemic lessons learned knowledge (Syllk) model is grounded in quality improvement. Adapts Reason’s (1997) Swiss cheese model to provide a basis for trend analysis and learn from incidents. The Syllk model considers the organisation in terms of people –learning, cultural and social elements and systems –technology, process and infrastructure. This paper applies the Syllk model at a large division of an Australian government organisation to determine if it can learn from past project experiences. |

Edwards, M. T. (2017). An organizational learning framework for patient safety. American Journal of Medical Quality, 32(2), 148-155. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Multi-mode |

Proposes an OL framework for patient safety with four major modes of organisational learning:(1) learning from the experiences of others as revealed in conversations and publications; (2) learning from the work of identifying and analysing process defects; (3) learning from the use of process and outcomes measures to provide feedback and drive the organization’s performance management system; and (4) learning from the results of responses to unexpected threats to quality and safety. |

Jenkin, T. A. (2013). Extending the 4I organizational learning model: Information sources, foraging processes and tools. Administrative Sciences , 3(3), 96-109. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Multi-level: 5I Model |

Extends Crossan et al.’s (1999) 4I model to include a fifth process, information foraging, and a fourth level, the tool. The resulting 5I OL model can be generalised to a number of learning contexts, especially those that involve understanding and making sense of data and information. |

Jerez-Gomez, P., Cespedes-Lorente, J. & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2005). Organizational learning capability: a proposal of measurement. Journal of Business Research , 58 (6), 715-725. |

Research paper |

Multi- dimensional |

Develops and tests a measurement scale for OL capability, consisting of four dimensions: managerial commitment, systems perspective, openness and experimentation, and knowledge transfer/integration. |

Kaur, N., & Hirudayaraj, M. (2021). The role of leader emotional intelligence in organizational learning: A literature review using 4I framework. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development , 33(1), 51-68. |

Literature review |

Mixed model: 4I + emotional intelligence |

Integrates 4I model with key aspects of emotional intelligence. Builds a case for emotionally intelligent leaders in supporting OL. |

Kim, D. H. (1993). The Link Between Individual and Organizational Learning. MIT Sloan Management Review , 35(1), 37-.50. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Integrated model: OADI- SMM |

Observe, Assess, Design, Implement –Shared Mental Model. OADI comprises the following stages: events or experiences are reflected upon to arrive at conclusions or hypotheses; these give rise to concepts and the individual’s mental models of the world; the models can then be tested against reality; the learning cycle begins again with observations of these experiments and their results. SMM is the transfer of this individual knowledge to the organisation. |

Law, K. M., & Gunasekaran, A. (2009). Dynamic organizational learning: a conceptual framework. Industrial and Commercial Training , 41(6), 314-320. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Continuous / cyclical |

Proposes an OL model as a series of repeated processes i.e., Driver>Enabler>Learning>Outcome. Drivers refer to the leaders, vision and mission of the organisation, enablers are the individuals, motivation, organisational culture, internal forces, learning includes project-based and action learning, team learning and individual learning, and the outcomes relate to performance and behavioural change. |

Lawrence, T. B., Mauws, M. K., Dyck, B., & Kleysen, R. F. (2005). The politics of organizational learning: Integrating power into the 4I framework. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 180-191. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

4I + integration of politics and power |

Connects specific learning processes of the 4I model to different forms of power. Intuition is linked with discipline, interpretation with influence, integration with force, and institutionalisation with domination. Suggests that in order to learn, organisations need active, interested members who are willing to engage in political behaviour that pushes ideas forward. |

Lewis, J. (2014). ADIIEA: An organizational learning model for business management and innovation. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management , 12(2), pp98-107. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Integrated model: ADIIEA |

Stands for Automation, Disruption, Investigation, Ideation, Expectation, and Affirmation. Also known as the ‘Innate Lesson Cycle’, where learning is based on knowing if something works. The suggestion is that organisations begin with automation. ‘Half-pipe’ cycles focus on automation, disruption and expectation, rocking back and forth between the three phases e.g., traditional training and education; while ‘full cycle’ thinking has organisations moving around all phases e.g., change and process management. |

Lipshitz, R., Popper, M., & Friedman, V. J. (2002). A multifacet model of organizational learning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 38(1), 78-98. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Multi-faceted |

Proposes structural, cultural, psychological and policy facets to an OL conceptual model. The structural facet refers to learning by organisation i.e., systems and mechanisms in place for processing and applying information. The cultural facet identifies five norms for OL: transparency, integrity, issue orientation, inquiry and accountability. The psychological facet refers to psychological safety and organisational commitment. The policy facet represents the formal and informal steps taken by management to promote OL. |

Malone, D. (2002). Knowledge management: A model for organizational learning. InternationalJournal of Accounting Information Systems, 3(2), 111-123. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Knowledge management |

Knowledge management refers to the ways firms capture and disseminate tacit processes of information evaluation. The model relies on an organisational structure that facilitates progressive filtration of ideas via knowledge networks, communities of practice, knowledge communities and project teams into its core practices. |

Mulholland, P., Domingue, J., Zdrahal, Z., & Hatala, M. (2000). Supporting organisational learning: an overview of the ENRICH approach. Information Services & Use , 20(1), 9-23 |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Multi-level |

Proposes the ENRICH approach, which incorporates theories of learning at the individual, group and organisational levels and intertwines working and learning. Draws from the OL literature to describe four types of learning across all three levels: reflection-in-action, domain construction, communities of practice and perspective taking. |

Murray, P. (2002). Cycles of organisational learning: a conceptual approach. Management decision , 40(3), 239-247. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

Integrated model: learning cycles |

Creates a new concept “unbounded learning”, where changing the rules and norms of the existing organisational system leads to simultaneous organisational change and growth. Unbounded learning is supported by a culture of adaptive learning, developing capabilities, generative learning and matching learning styles to various situations. |

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization science , 5(1), 14-37. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

SECI model for knowledge creation |

Stands for socialisation, externalisation, combination, internalisation. The SECI model describes a cycle where tacit knowledge is converted to and from explicit knowledge. The focus is on two types of knowledge, with four modes of conversion between them. |

Provera, B., Montefusco, A., & Canato, A. (2010). A ‘no blame’ approach to organizational learning. British Journal of Management, 21(4), 1057-1074. |

Persuasive/ analytical paper |

No-blame approach |