Health-professional communication skills and competencies in Australia: an interprofessional content analysis

Shannon Saad 1,

Fiona Bogossian

1,

Fiona Bogossian 2,

Stevie-Jae Hepburn

2,

Stevie-Jae Hepburn 2,

Michele Verdonck

2,

Michele Verdonck 2,

Kelly Lambert

2,

Kelly Lambert 3,

Debra Kerr

3,

Debra Kerr 4,

Katie Healy

4,

Katie Healy 5,

Judy Mullan

5,

Judy Mullan 6,

Kerry Peek

6,

Kerry Peek 7,

Natalie Dodd

7,

Natalie Dodd 2*

2*

Abstract

Purpose: Effective communication is central to safe and effective interprofessional collaboration and person-centred care within healthcare systems. A significant proportion of patient complaints and adverse outcomes in Australia are related to communication issues. The aim of this study was to compare and contrast the descriptions of communication skills across nine health-professional competency standards using content analysis.

Methodology: Researchers from nine distinct health professions used an interprofessional methodology to extract and organise terms related to healthcare communication from professional competency standards documents.

Findings: Eight domains, with 31 subdomains, were identified and compared by health profession and by overall subdomain frequency. There was a lack of standardised structure for professional practice standards and frequent embedding of communication skills within other core competencies. Also common was imprecise language regarding healthcare communication requirements, and definitions of terms were often lacking.

Practical implications: Consistent representation of some domains and subdomains across health professions could be a precursor to the development of common communication competencies. These could serve as a benchmark for program accreditations, professional bodies, and interprofessional or healthcare communication education.

Value: This research adds value due to the interprofessional research method, which modelled interprofessional collaborative practice and allowed interpretation of professional competency standards through a multiprofessional lens.

Limitations: Nine professional competency standards were included, representing the nine professions of the researchers; therefore, some professional competency standards were not included in the analysis.

Keywords: Interprofessional education, interprofessional collaborative practice, health professions research, communication skills, professional competencies, professional standards

- RPA Virtual Hospital, Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, Australia

- School of Health, University of the Sunshine Coast, Sippy Downs, Australia

- School of Medical, Indigenous and Health Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia

- Institute for Health Transformation, Centre for Quality and Patient Safety, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Deakin University, Burwood, Australia

- Sunshine Coast Hospital and Health Service, Birtinya, Australia

- School of Health Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

- Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia

*Corresponding author: Dr Natalie Dodd, University of the Sunshine Coast, University Way, Sippy Downs QLD 4556, Australia, [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

In 2010 the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice, which identified mechanisms that shape successful collaborative teamwork in health professions (WHO 2010). Interprofessional education occurs when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other, and is essential to developing an effective collaborative-practice ready workforce (WHO 2010). This framework called on health and education systems to work together to coordinate health workforce strategies that fit with local contexts, and to create policy and regulatory frameworks that support educators and health workers to promote and practice collaboratively.

The competency domain of communication between health professions includes developing and integrating attitudes, behaviours, values, and judgements necessary for collaborative practice. The widely adopted framework from the Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (2010) emphasises two domains: interprofessional communication; and person/client/family/community-centred care. These domains support and influence the remaining four domains –role clarification, team functioning, interprofessional conflict resolution and collaborative leadership. The interprofessional communication competency statement identifies that ‘Learners/practitioners from different professions communicate with each other in a collaborative, responsive and responsible manner’ (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative 2010, p.16).

In the same year in Australia, state and territory governments established the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS) (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023) to ensure that all regulated health professionals are registered against consistent, high-quality national professional standards. The Australian health practitioner regulation agency (Ahpra) prioritises patient safety. It administers the NRAS and provides administrative support to 15 national boards for healthcare professions across five core regulatory functions: professional standards, registration, notification, compliance and accreditation (of education providers and education programs). Accreditation and practice standards provide system-level support and protection of patient safety (Ahpra and National Boards 2023). Health discipline standards include interpersonal skills, knowledge, values and behaviours, thereby providing consistency for health educators, clinicians and persons/clients regarding quality and standards of care (Verma 2006). Health and social professions that do not fall under Ahpra governance are considered self-regulating and may be part of other independent bodies that provide quality frameworks, for example, the National Alliance of Self Regulating Health Professions (NASRHP). All health organisations and professionals are required to adhere to the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards, which have two key domains relevant to communication: communication for safety, and partnering with consumers (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care [ACSQHC] 2021).

Despite attempts to address the human and systems factors to make health care safer, it is estimated that in developed countries, over 17 million adverse events occur each year (Jha et al. 2013), making healthcare errors the third leading cause of death in the US after cancer and heart disease (Makary & Daniel 2016). In Australia 900,000 patients suffer adverse events each year. One in nine hospitalised patients will suffer a complication, and with overnight admission the risk rises to one in four (ACSQHC 2021). Many of these complications are avoidable, and some lead to permanent disability and death (The Joint Commission 2023). It has been noted that ‘communication breakdowns (e.g., not establishing a shared understanding or mental model across care team members, or no or inadequate staff-to-staff communication of critical information) continue to be the leading factor contributing to sentinel events’ (The Joint Commission 2023, p.2).

Effective communication is not only important in collaborative practice (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative 2010, ACSQHC 2020), it also facilitates person-centred care, as it elicits the values, needs and desires of the patient (Silverman, Kurtz & Draper 2013). From the perspective of patients, it is one of three core components of person-centred care, alongside partnership and health promotion (Little et al. 2001). Between 2000 and 2011, 18,907 written patient complaints were made to Australian statutory health service commissions against 11,148 doctors (Bismark et al. 2013). Almost one quarter of these complaints addressed communication issues, including concerns about a doctor’s attitude or manner (15%), and the quality or amount of information provided (6%). Internationally, patient complaints regarding communication in the healthcare setting are wide-ranging across institutions, departments and healthcare roles (including managers) (Skär & Söderberg 2018).

The practice of registered health professionals in Australia is governed by profession-specific standards for practice, which may contain reference to communication skills and competencies. Shared expectations about communication skills are expressed in documents such as the Code of Conduct (Ahpra and National Boards 2022) which has been endorsed by 12 health professions (excluding, e.g., medicine, midwifery, nursing and dietetics, which have their own discipline-specific codes). While shared codes are developed collaboratively, discipline-specific codes are informed within and by the specific discipline. In addition, there are national standards that promote safety and quality in healthcare and guide the communication of health care providers (ACSQHC 2024). Despite the range of documents guiding the practices, conduct and competencies of health professions, there are variations in the content and definitions provided.

Just as interprofessional communication underpins interprofessional collaborative practice across disciplines, interprofessional research plays an important role in addressing complex problems whose solutions are beyond the scope of a single discipline or field of research. Interprofessional research involves two or more professional teams or individuals working together to advance fundamental understanding and/or solve problems that are beyond the scope of a single discipline or field of research practice (Green & Johnson 2015). The National Institutes of Health calls this research approach ‘team science’, an approach that not only involves working together, but it is also a collaborative-practice approach that aims to result in evidence-driven person care (Little et al. 2017)

Therefore, using an interprofessional research approach, the aims of this study were to:

- Compare and contrast evidence of communication skills in professional competency standards for health professions in Australia

- Consider the implications of this study for interprofessional healthcare education and future iterations of professional competency standards.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY TYPE

This is an interprofessional research study (content analysis conducted by an interprofessional team). Interprofessional research is when health care professionals from differing professions collaborate, using their unique knowledge and skills, and valuing differing viewpoints to enhance collective understanding (De La Armas 2024).

SAMPLING AND RECRUITMENT

Our purposive sampling aimed to recruit a range of health professionals.

The study was promoted through the International Association for Communication in Healthcare (EACH 2024). The recruitment process sought to identify healthcare professionals who had an interest and/or expertise in communication skills training and/or research for healthcare professionals. Potential participants were invited to attend an online meeting to discuss the study.

PARTICIPANTS

There were nine participants from distinct health professions: medicine, midwifery, registered nursing, dietetics, occupational therapy, paramedicine, pharmacy, physiotherapy and speech pathology.

MATERIALS

Current professional competency standards, capability standards, program accreditation standards and graduate outcome statements (hereinafter named professional competency standards) were identified from national Health Practice Board websites (Australian Medical Council Limited [AMC] 2023, Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2018, Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2016, Dietitians Australia 2021, Occupational Therapy Board of Australia 2019, Paramedicine Board of Australia 2021, Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2016, Physiotherapy Board of Australia and Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand 2015, Speech Pathology Australia 2023). A representative document was included for each health profession, with selection based on equivalency in providing explicit descriptions of the capabilities of each type of health practitioner. To conserve equivalence of documents for the purposes of comparison, other definitional documents were not included, for example, post-graduate medical college competency statements or other health-professional practice standards.

Table 1: Professional competency standards used in the study analysis

Profession |

Document Name |

Regulatory Body |

Year of Publication |

Medicine |

Standards for the assessment and accreditation of primary medical programs |

Ahpra |

2023 |

Midwifery |

Midwife standards for practice |

Ahpra |

2018 |

Nursing |

Registered nurse standards for practice |

Ahpra |

2016 |

Nutrition and Dietetics |

National competency standards for dietitians in Australia |

NASRHP |

2021 |

Occupational Therapy |

Australian occupational therapy competency standards |

Ahpra |

2018 |

Paramedicine |

Professional capabilities for registered paramedics |

Ahpra |

2021 |

Pharmacy |

National competency standards framework for pharmacists in Australia |

Ahpra |

2016 |

Physiotherapy |

Physiotherapy practice thresholds in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand |

Ahpra |

2015 |

Speech Pathology |

Professional standards for speech pathologists in Australia |

NASRHP |

2020 |

The nine documents analysed are listed in Table 1. The majority of documents reviewed were professional or competency standards, with only one profession (medicine) having accreditation standards/graduate outcome statements analysed (AMC 2023). In the analysis of the AMC document, only the glossary and graduate outcome statements were included (AMC 2023). This decision was based on a scoping review, which revealed that the remaining sections lacked relevance and were not equivalent to the corresponding documents of other health professions. The recency of the documents ranged from 2013 (physiotherapy) (Physiotherapy Board of Australia and Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand 2015) to 2023 (medicine) (AMC 2023).

ANALYSIS

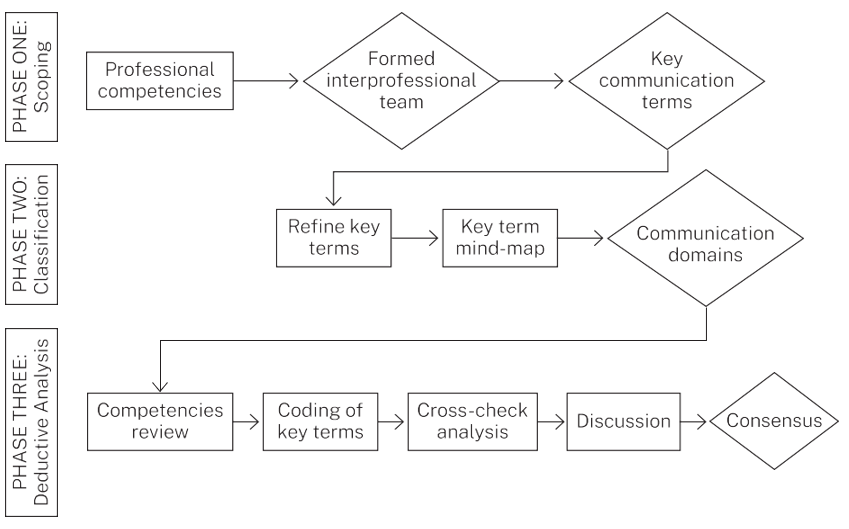

Content analysis was conducted between October 2022 and May 2023. The study was undertaken in three phases: Phase 1 –Scoping, Phase 2 – Classification, and Phase 3 –Deductive Analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Phases of the professional competency standards content analysis

Phase 1 –Scoping

An initial scope of the standards was completed by one researcher (SH) utilising key terms relating to healthcare communication. These were provided by the wider research team, who had expertise in health professions communication. The scoping process confirmed a broad range of content that would be amenable to more detailed content analysis. The research team was then divided into dyads or triads. Each team member reviewed their own standards and those of one other profession and extracted terms they perceived to pertain to communication (conceptual content analysis). The professional lens of each reviewer was integral to the interpretation of the practice standard for their health profession. The findings from each profession were recorded on a spreadsheet. Dyads or triads met to discuss key communication terms identified and resolved any discrepancies in interpretation of data.

Phase 2 –Classification: Refinement of key terms

The wider research team met to share the findings from the smaller groups and discuss the presence (or absence) of key terms across the nine professions, and to reach consensus on adjustments of key terms.

Two members of the research team (ND, MV) mapped the key terms using a digital mind-map to arrange the terms into broader categories (domains) with nested elements (subdomains) to aid consistency of analysis between groups. The mind map and categorisations were presented back to the research team for discussion and refinement according to consensus.

Phase 3 –Deductive analysis

Each team member extracted statements (data points) from their professional competency standards and recorded these against the domains and subdomains derived from Phase 2. Data were assigned identifiers to enable the tracing of the source location within the professional standards.

Participants then worked in their dyad/triad groups to review their counterparts’ professional competency standards to analyse, confirm and record data extraction. Each group met to resolve any discrepancies and reach consensus. Following this, the larger group met to discuss the key findings via teleconferencing.

A comprehensive audit trail was maintained. This included shared spreadsheets, meeting minutes and transcriptions of interprofessional discussions related to the research results. One member of the research team (SS) collated all the coded data to quantify the frequency of data points relating to the domains and subdomains. These data were documented in a shared excel spreadsheet to inform participants of results.

RESULTS

The documents were noted to have variations in style and structure, as well as the number of nested domains and subdomains that classified the professional competency standards. The study results presented below will first describe broad commonalities and differences, and will conclude with quantitative results providing the frequency of communication skills within each domain and subdomain.

TERMINOLOGY

Terminology varied between professional competency statements. Some used the plural first-person pronoun “we” (speech pathology) (Speech Pathology Australia 2023) to refer to the health practitioner, whereas some used formal third person, for example, “an occupational therapist” (Occupational Therapy Board of Australia 2019). Persons receiving healthcare were referred to as a patient (medicine and paramedicine) (AMC 2023, Paramedicine Board of Australia 2021), patient/client (pharmacy, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and dietetics) (Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2016, Occupational Therapy Board of Australia 2019, Physiotherapy Board of Australia and Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand 2015, Dietitians Australia 2021), woman (midwifery) (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2018), individual (speech pathology) (Speech Pathology Australia 2023), and person/people (nursing) (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2016).

GLOSSARIES

The participants noted variations in how communication skills were described. Glossaries that provided some definitional detail regarding communication terms were found in many of the practice standards documents, though with varying degrees of specific detail. For example, the paramedicine practice standard outlined the following:

Communication techniques must include active listening, use of appropriate language and detail, use of appropriate verbal and non-verbal cues and language, written skills and confirming that the other person has understood (Paramedicine Board of Australia 2021, p. 5).

In contrast, the medicine standard (AMC 2023, p. 5) mentioned communication in relation to its functionality in partnerships. ‘Partnerships or partnering with patients comprises many different, interwoven practices –from communication and structured listening, through to shared decision making, self-management support and care planning …’.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS

Specific communication techniques were infrequently referred to within professional competency standards. For example, the medicine standard (AMC 2023) used terms such as listening and responsive whereas midwifery standards (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2018) referred to the quality of communication (e.g., compassion, cultural sensitivity) rather than the specific techniques. The standard for nursing (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2016) lacked specific description of communication skills, using instead phrasing such as good communication. Other standards used terms like engage, empower, advocate and respond, without direct reference to communication techniques, but implying outcomes associated with effective and skilled communication.

There were different foci on verbal and written communication skills that varied between standards. For example, some standards included a requirement for specific written abbreviations (midwifery, paramedicine) (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2018, Paramedicine Board of Australia 2021). Standards also reflected changes in expectations regarding clinical documentation in keeping with digital health initiatives, with an evolution to the use of electronic medical records.

Through the analysis process, eight major communication domains emerged, these were: person-centred communication, desirable qualities in healthcare communication, rapport building, adapting to manage barriers, information management, interprofessional collaborative practice, cultural safety in communication, and professional characteristics of communication. There were 31 subdomains underpinning these domains (see Table 2).

The frequency of datapoints identified from the practice standards is shown in Table 3 by subdomain, allowing an appreciation of the relative weightings of domains and subdomains. The subdomains most frequently documented in the practice standards were: consults interprofessionally (54), shared decision making (53) and culturally responsive (37). Due to the heterogeneity of the formats and styles of the practice standard documents, a comparison of subdomain frequency by health profession was not undertaken. For example, the practice standard for physiotherapy had numerous items identified for many subdomains, but this was due to the multiple layers of nesting subdomains within the standard, and resulted in designed repetition rather than novel or extended coverage (Physiotherapy Board of Australia and Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand 2015).

Table 2: Domains and subdomains (with expanded descriptors) in professional competency standards for health care communication

| Domain | Subdomain |

| Patient-centred communication | Shared decision making, reviews evaluates and modifies plans with client, partnership, communicates assessments and outcomes |

| Patient education | |

| Consent, autonomy | |

| Advocacy | |

| Desirable qualities in healthcare communication | Timely |

| Effective, appropriate, purposeful | |

| Respectful, sensitive, compassionate, empathy | |

| Responsive, patient feedback | |

| Open | |

| Rapport building | Relationships (building, maintenance, concluding) |

| Trust | |

| Adapting to manage barriers | Uses interpreters |

| Adapts (verbal/nonverbal/written) communication | |

| Information management | Collect relevant, accurate information, information gathering |

| Comply with legal and procedural requirements | |

| Documentation, accurate record keeping | |

| Digital literacy, information technology (skills in) | |

| Interprofessional collaborative practice | Feedback from colleagues |

| Understanding of roles | |

| Consults interprofessionally, multidisciplinary collaboration, interprofessional collaboration, referral | |

| Role promotion | |

| Cultural safety in communication | Culturally responsive communication tools and strategies, understand and incorporate relevant culture protocols |

| Cultural respect | |

| Professional characteristics of communication | Professional boundaries |

| Communicates clinical reasoning | |

| Ethical, accountable, responsible | |

| Confidentiality | |

| Patient safety (handover, graded assertiveness) | |

| Manage conflict | |

| Education in the health professions | |

| Avoids bias |

Table 3: Frequency of communication subdomains (abbreviated) and gaps identified in professional competency standards of nine health professions (HPs) in Australia

| Domain | Sub-domain | Dietetics | Medicine | Midwifery | Occupational therapy | Paramedicine | Pharmacy | Physiotherapy | Registered Nursing | Speech Pathology | Frequency (all HPs) | Gaps (per subdomain) |

| Patient-centred communication | Shared decision making |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

53 | 0 |

| Patient education |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 | 0 | |||

| Consent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 | 0 | |

| Advocacy |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 | 0 | ||

| Desirable qualities in healthcare communication | Timely |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 | 2 |

| Effective; Appropriate |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 | 1 | |

| Respectful; Sensitive |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 | 0 | |||

| Responsive |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 | 3 | ||

| Open |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 | 6 | ||

| Rapport building | Relationship building |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 | 1 |

| Trust |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 | 3 | ||

| Adapting to manage barriers | Use interpreters |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 | 7 |

| Adapts |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 | 3 | ||

| Information management | Collect information |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 | 0 |

| Comply legal |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 | 1 | |

| Accurate records |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 | 0 | |

| Digital literacy |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 | 2 | |

| Interprofessional collaborative practice | Feedback |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 | 2 |

| Understanding roles |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 | 5 | |||

| Consults interprofessionally |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

54 | 0 | |

| Role promotion |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 | 3 | |

| Cultural safety in communication | Culturally responsive |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

37 | 0 | |

| Cultural respect |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 | 0 | |

| Professional characteristics of communication | Professional boundaries |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 | 0 | |

| Clinical reasoning |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 | 0 | |

| Ethical; Accountable |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 | 0 | |

| Confidentiality |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 | 3 | |

| Patient safety |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 | 1 | |

| Manage conflict |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 | 3 | ||

| Education in HPs |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

29 | 1 | |||

| Avoids bias |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 | 5 | |

| Total gaps per HP | 4 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 5 |

The term “gap” was used in this study to indicate where the research team could not find sufficiently explicit or communication-relevant reference to a subdomain in the respective health-profession practice standard, that is, no datapoints identified. Of the 31 subdomains, there were 13 that had no gaps identified, meaning they were represented in all the professional competency standards. In the domain person-centred communication, all subdomains were present in all nine health professions competency standards, which was also true for the two subdomains of the cultural safety domain. Gaps in communication skill-type subdomains for the health professions ranged from two to nine. Paramedicine (Paramedicine Board of Australia 2021) was found to have the least number of gaps (two), while nursing (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2016) and midwifery (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2018) had the largest number of gaps (nine each) (Table 3).

PATIENT-CENTRED COMMUNICATION

This domain, a cornerstone of quality in Australian healthcare, included four subdomains that were documented in all practice standards. The subdomain of shared decision making was the most strongly represented, occurring 53 times across the standards, which was the second highest frequency in the study (Table 3).

DESIRABLE QUALITIES IN HEALTHCARE COMMUNICATION

This domain included five subdomains, with two subdomains, effective (8/9) and respectful (9/9), included in the majority of health professions, contrasting with the subdomain open (3/9), which was the least represented across the health professions (Table 3).

RAPPORT BUILDING

This domain included the smallest number of subdomains (two). The interprofessional research team preserved it as a unique domain due to the shared perception of the centrality of the therapeutic relationship to effective healthcare communication. The subdomain relationship building was consistently present (8/9) with a strong frequency (18), contrasting with the subdomain trust, present in one third of the health professions included in this study (3/9, frequency of 7) (Table 3).

ADAPTING TO MANAGE BARRIERS

Similar to rapport building, this was maintained as a separate domain due to its perceived high significance in the provision of inclusive and universal healthcare. General or specific adaptions to verbal/non-verbal or written communication were present in the majority of health professions (adapts: 6/9, frequency of 14), though the specific ability to use healthcare interpreters (use interpreters) was only present on one occasion for each of two health professions (paramedicine and speech pathology) (Table 3).

INFORMATION MANAGEMENT

The subdomains for information management showed few gaps in representation (0–2) reflecting the shared importance of this domain in health professions’ practice. The subdomains collect information and accurate records were present in all the health professions included in this study (9/9) (Table 3).

INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE

The subdomain consults interprofessionally was the most strongly represented across all health-profession practice standards and had the highest frequency identified (54), consistent with registering bodies (Ahpra) requiring the inclusion of interprofessional practice in health professions competencies. In comparison, the remaining three subdomains were less strongly represented (Table 3).

CULTURAL SAFETY IN COMMUNICATION

The two subdomains related to cultural safety showed no gaps, with culturally responsive present in all standards at the third highest frequency in the study (37) (Table 3).

PROFESSIONAL CHARACTERISTICS OF COMMUNICATION

Of the eight subdomains, three had no gaps identified: ethical/accountable, professional boundaries, and clinical reasoning. Patient safety and education in the health professions were also strongly represented, with only one gap each (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Effective healthcare communication promotes safe and optimal patient care, team functioning and resource efficiency (Umberfield et al. 2019, Burke, Downey & Almoudaris 2022). This study used an interprofessional lens to analyse evidence of the inclusion of communication skills in the professional competency standards of nine health professions. The documents examined in this study were noted to have variations in style and structure; thus, the gaps identified may more reflect these differences, and differences between the professions, rather than true omissions of the subdomains. For example, the subdomain avoids bias, which had many gaps, may be considered by some professions to be implicit in other subdomains, or may have been avoided due to its use of negative phrasing. Overall, the professional competency standards included in this study showed consistency in their inclusion of communication competencies relating to the domains of patient-centred communication, cultural responsiveness, interprofessional collaboration and information management. While this consistency may be influenced by the accreditation requirements of Ahpra, two of the health professions included here are not subject to Ahpra regulation. Subdomains relating to desirable qualities and professional attributes of communication, including such attributes as responsiveness and ethics, were also consistently represented. This implies that Australian healthcare teams are expected to respectfully engage persons in holistic and responsive caring relationships, working within an ethical and legal framework.

Our findings regarding the healthcare communication domains and subdomains in the professional standards are consistent with the findings of research that analysed and synthesised learning outcomes in published studies on healthcare communication (Denniston et al. 2017). Other research that has examined healthcare professional standards and competency statements has likewise elucidated similarities as a unifying force for the benefit of healthcare quality, interprofessional practice and patient experiences and engagement with healthcare (Grace et al. 2017). Content analysis of standards documents has also been used to assess the consistency and accountability of the health professions towards important emerging principles (such as interprofessional education and collaboration), enabling an overview of the pattern of barriers, and an elucidation of the opportunities and shared learnings (Bogossian & Craven 2021).

Training for effective communication, a core skill essential to clinical competence (Silverman, Kurtz & Draper 2013), should include repeated, deliberate practice within defined curriculums. Not all practice standards defined communication skills clearly, which has implications for teaching and assessing communication skills within professional capabilities, in both the undergraduate and professional arenas. Teaching and assessment should focus on specific skills, with clear learning objectives. If the standards themselves lack clarity or require individuals to interpret the meanings of particular words or phrases, there may be a lack of shared understanding of what constitutes effective communication. Given that health professionals generally work in interprofessional teams, a clear and shared understanding of specific communication skills could facilitate improved education in healthcare communication; hence, more effective interprofessional collaborative practice.

Developing a shared set of Australian healthcare communication competencies, using an interprofessional approach that embraces commonalities and respects uniqueness among the professions, lays important foundational work for the development of interprofessional curriculums in diverse healthcare education institutions, including universities and health services. There is ample reason to prioritise interprofessional education for the benefit of enhanced collaborative practice to improve healthcare delivery and patient outcomes. While overarching frameworks have been proposed (White et al. 2023), the outlining of specific competencies with associated definitional statements would enable the design of interprofessional healthcare curriculums to support improved interprofessional practice. The Ahpra Code of Conduct (Ahpra and National Boards 2022) provides guidance on aspects of healthcare communication, though it is endorsed by only four of the health professions included in this study. The Code of Conduct relies on the foundational concept that core values are shared by the healthcare professions, and that making these explicit supports patient interests, legal and regulatory requirements, and healthcare quality. While the Code of Conduct (Ahpra and National Boards 2022) has significant content that overlaps with the findings of this study, it is not specifically tailored to communication and does not have the endorsement of nursing or medicine – two key health professions.

Accuracy in written communication, including abbreviations, is vital to ensure compliance with relevant Commonwealth, state and territory legislation. Interestingly, abbreviations vary from state to state in Australia, with each state government health department defining their own abbreviations. National recommendations also exist, and are relevant to all health professions, for example, the ACSQHC provides recommendations for terminology, abbreviations and symbols used in medicines documentation (Raban et al. 2023). Designers of professional competency standards could consider including references or links to national bodies such as the ACSQHC to ensure consistency in communication across health professions.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Interprofessional approaches were used to guide the research (Green & Johnson 2015) and writing of this manuscript (Vogel et al. 2019). Working in dyads and triads afforded individual team members the ability to closely examine the practice standards of another health profession, and this process, combined with whole-of-team discussions, resulted in team members learning with, from and about the other professions. The interprofessional research methodology used, where interlocking diverse professional views creates an interdependent view of the research and healthcare (Ormond et al. 2023), brings an innovative perspective to the project, beyond a discrete and multidisciplinary approach. The processes of data analysis were meticulous, and the rigour with which key terms and high-level domains were extracted, reviewed and reconfirmed, strengthens the authenticity of the findings.

Although professional competency standards documents are an easily accessible source of research data, the extent to which they accurately reflect day-to-day clinical practice is debatable. Practicing clinicians may have little to no knowledge of their standards and the social and regulatory forces outside their professional bodies that shape them. The practice standards used in this study varied in recency of publication, implying that professional practice may have evolved since the time of release. These documents are updated periodically, so our findings are derived from those that are current and publicly available. Due to the comparative design of this study, other documents used by professional bodies were not included in this study, for example, the Professional Practice Standards of the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2023). This limits the extent of the definitional material that was examined and may result in unknown omissions from the raw dataset.

Our findings relate to the nine health professions included in this study in the Australian context and generalisation to other health professions internationally should be cautious.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The findings from this paper support the feasibility and utility of a shared set of healthcare communication competencies to inform the design of interprofessional educational (IPE) activities and enhance interprofessional collaborative practice. Ideally, these IPE activities would be developed using an explicit interprofessional methodology that interlocks perspectives to merge commonalities while respecting and preserving uniqueness. Further work defining and describing the theoretical and practical aspects of interprofessional methodologies is needed to ensure rigour and applicability.

Future works aiming to define and prescribe how healthcare is delivered in Australia should prioritise the involvement of healthcare consumers, caregiver advocates, and representatives of diverse communities. While patient health outcomes are of compelling importance, the experience of receiving healthcare informs and ensures essential quality and safety aspects of healthcare services.

Funding

This work was supported by Griffith University, School of Medicine, under a 2021 internal grant scheme (no grant number), designed to accelerate research after delays secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

Ahpra and National Boards 2022, Code of conduct, Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra), Melbourne, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.Ahpra.gov.au/Resources/Code-of-conduct/Shared-Code-of-conduct.aspx

Ahpra and National Boards 2023, Annual report 2022/23, Ahpra,

Melbourne, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.ahpra.gov.au/Publications/Annual-reports/Annual-report-2023.aspx

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2020, Communicating for safety: improving clinical communication,

collaboration and teamwork in Australian health services , ACSQHC, Sydney.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2021, National safety and quality health service standards, 2nd edn, ACSQHC, Sydney.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2024, Communicating for safety standard, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/communicating-safety-standard

Australian Medical Council Limited 2023, Standards for assessment and accreditation of primary medical

programs, viewed 30 June 2025, https://www.amc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/AMC-Medical_School_Standards-FINAL.pdf

Bismark, MM, Spittal, MJ, Gurrin, LC, Ward, M & Studdert, DM 2013,

‘Identification of doctors at risk of recurrent complaints: a national

study of healthcare complaints in Australia’, BMJ Quality & Safety, vol. 22, pp. 532-40, viewed 19 June 2025, https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/qhc/22/7/532.full.pdf

Bogossian, F & Craven, D 2021, ‘A review of the requirements for

interprofessional education and interprofessional collaboration in

accreditation and practice standards for health professionals in

Australia’, Journalof Interprofessional Care,vol. 35,

pp. 691-700, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13561820.2020.1808601

Burke, JR, Downey, C & Almoudaris, AM 2022, ‘Failure to rescue

deteriorating patients: a systematic review of root causes and

improvement strategies’, Journal of Patient Safety,vol. 18, no.

1, pp. e140-e155, viewed 19 June 2025, https://journals.lww.com/journalpatientsafety/fulltext/2022/01000/failure_to_rescue_deteriorating_patientsa.28.aspx

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative 2010, A national interprofessional competency framework, CIHC, Vancouver, viewed 19 June 2025, https://phabc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CIHC-National-Interprofessional-Competency-Framework.pdf

De La Armas, E 2024, ‘Interprofessional

research: a concept analysis’, InternationalJournalofCaringSciences,

vol. 17, pp. 903-908.

Denniston, C, Molloy, E, Nestel, D, Woodward-Kron, R & Keating, JL 2017, ‘Learning outcomes for communication skills across the health professions: a systematic literature review and qualitative synthesis’, BMJ Open,vol. 7, pp. e014570, viewed 19 June 2025, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/4/e014570

Department of Health and Aged Care 2023, National registration and accreditation scheme, viewed 19 June 2025, https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/working-dietetics/standards-and-scope/national-competency-standards-dietitians

Dietitians Australia 2021, National competency standards for dietitians, viewed 19 June 2025, https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/working-dietetics/standards-and-scope/national-competency-standards-dietitians

EACH 2024, InternationalAssociationforCommunicationinHealthcare,

EACH,viewed 19 June 2025, https://each.international/

Grace, S, Innes, E, Joffe, B, East, L, Coutts, R & Nancarrow, S 2017, ‘Identifying common values among seven health professions: an interprofessional analysis’, Journal of Interprofessional Care, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 325-34, viewed 19 June 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28272909/

Green, BN & Johnson, CD 2015, ‘Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future’, The Journal of Chiropractic Education,vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 1-10, viewed 19 June 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4360764/

Jha, AK, Larizgoitia, I, Audera-Lopez, C, Prasopa-Plaizier, N, Waters, H

& Bates, DW 2013, ‘The global burden of unsafe medical care:

analytic modelling of observational studies’, BMJ Quality & Safety, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 809-15, viewed 19 June 2025, https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/22/10/809

Little, MM, St Hill, CA, Ware, KB, Swanoski, MT, Chapman, SA, Lutfiyya,

MN & Cerra, FB 2017, ‘Team science as interprofessional

collaborative research practice: a systematic review of the science of

team science literature’, Journal of Investigative

Medicine,vol. 65, pp. 15-22, viewed 19 June 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5284346/

Little, P, Everitt, H, Williamson, I, Warner, G, Moore, M, Gould, C,

Ferrier, K & Payne, S 2001, ‘Preferences of patients for patient

centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study’, BMJ,vol.

322, pp. 468-75, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/322/7284/468.full.pdf

Makary, MA & Daniel, M 2016, ‘Medical error—the third leading cause

of death in the US’, BMJ,vol. 353, pp. i2139, viewed 19 June

2025, https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/353/bmj.i2139.full.pdf

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2016, Registered nurse standards for practice, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Statements/Professional-standards/registered-nurse-standards-for-practice.aspx

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia 2018, Midwife standards for practice, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/codes-guidelines-statements/professional-standards/midwife-standards-for-practice.aspx

Occupational Therapy Board of Australia 2019, Australian Occupational Therapy Competency Standards, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.occupationaltherapyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines/Competencies.aspx

Ormond, T, Sheehan, D, Meeks, M, Dean, J & Joyce, L 2023, ‘Is it

time for an interprofessional research methodology?’, Australia and New Zealand Association of Health Professions

Educators. Gold Coast, 26-29 June 2023.Queensland, Australia.

Paramedicine Board of Australia 2021, Professionalcapabilities

forregistered paramedics,viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.ahpra.gov.au/documents/default.aspx?record=WD20%2F30356&dbid=AP&chksum=pygEs5pQbxl9KDQNKlgYkA%3D%3D

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2023, Professional PracticeStandards(Version

6),viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.psa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/5933-Professional-Practice-Standards_FINAL-1.pdf

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2016, NationalCompetency

Standards,viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.psa.org.au/practice-support-industry/national-competency-standards/

Physiotherapy Board of Australia and Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand 2015, Physiotherapy practice thresholds in Australia & Aotearoa New Zealand, viewed 19 June 2025, https://cdn.physiocouncil.com.au/assets/volumes/downloads/Physiotherapy-Board-Physiotherapy-practice-thresholds-in-Australia-and-Aotearoa-New-Zealand.PDF

Raban, MZ, Merchant, A, Fitzpatrick, E & Magrabi, F 2023, Recommendations for terminology, abbreviations and symbols used in medicines documentation: a rapid literature review, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Sydney, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/safer-naming-and-labelling-medicines/recommendations-terminology-abbreviations-and-symbols-used-medicines-documentation

Silverman, J, Kurtz, S & Draper, J 2013, Skills for communicating with patients, CRC press, Boca Raton.

Skär, L & Söderberg, S 2018, ‘Patients’ complaints regarding healthcare encounters and communication’, Nursing Open,vol. 5, pp. 224-232, viewed 19 June 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5867282/

Speech Pathology Australia 2023, Professional Standards for Speech Pathologists in Australia, viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/Public/Public/About-Us/Ethics-and-standards/Professional-standards/Professional-Standards.aspx

The Joint Commission 2024, Sentinel Event Data 2023 Annual Review , viewed 19 June 2025, https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/2024/2024_sentinel-event-_annual-review_published-2024.pdf

Umberfield, E, Ghaferi, AA, Krein, SL & Manojlovich, M 2019, ‘Using incident reports to assess communication failures and patient outcomes’, Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety,vol. 45, pp. 406-13, viewed 19 June 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6590519/

Verma S, Paterson M, Medves J 2006. ‘Core competencies for health care professionals: what medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy share’, Journal of Allied Health, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 109-115.

Vogel, MT, Abu-Rish Blakeney, E, Willgerodt, MA, Odegard, PS, Johnson, EL, Shrader, S, Liner, D, Dyer, CA, Hall, LW & Zierler 2019, ‘Interprofessional education and practice guide: interprofessional team writing to promote dissemination of interprofessional education scholarship and products’, Journal of Interprofessional Care,vol. 33, pp. 406-13, viewed 19 June 2025, https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1538111

White, SJ, Condon, B, Ditton-Phare, P, Dodd, N, Gilroy, J, Hersh, D, Kerr, D, Lambert, K, Mcpherson, ZE, Mullan, J, Saad, S, Stubbe, M, Warren-James, M, Weir, KR & Gilligan, C 2023, ‘Enhancing effective healthcare communication in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand: considerations for research, teaching, policy, and practice’, PEC Innovation,vol. 3, pp. 100221, viewed 19 June 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10562187/

World Health Organization 2010, Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice,WHO, Geneva.