Preparedness for internship – a mixed-methods evaluation of the assistant in medicine program

Madeleine de Carle  1,

Ricci Barel

1,

Ricci Barel  1,

Bethany Greentree

1,

Bethany Greentree  1,

Conor Gilligan

1,

Conor Gilligan  2,

Bunmi Malau-Aduli

2,

Bunmi Malau-Aduli  1,

Nicolas Zubrzycki

1,

Nicolas Zubrzycki  3,

Hemal Patel

3,

Hemal Patel  1

1

Abstract

Purpose: The transition from medical student to doctor is often daunting. With compulsory hands-on clinical exposure and pre-internship training included in Australian medical education, this study aims to explore whether the Assistant in Medicine (AiM) program contributed to students’ feelings of internship preparedness.

Methodology: Participants were 2022–2023 alumni of the Joint Medical Program (JMP), run by the Universities of Newcastle and New England. All participants completed the Embedded Senior Medical Student (ESMS) program, a pre-internship program integrated into the final-year curriculum. Most participants also chose to participate in the AiM program. A mixed-method design was utilised to explore the experiences and perceived preparedness for internship. Part 1, a questionnaire, was distributed to eligible participants, focusing on common activities undertaken as a medical student and/or AiM. Identified patterns were used to guide Part 2, focus group discussions.

Findings: While the survey data suggested that ESMS students and AiMs had similar exposures to tasks/procedures, focus group discussions revealed key differences in terms of level of independence of practice, type of work performed, sense of responsibility and opportunities to receive teaching.

Research implications: This study contributes to the growing body of literature investigating the impact of the AiM program on medical student experience. It also highlights aspects of medical education perceived as valuable for internship preparedness.

Practical implications: Further research exploring the AiM program should be utilised to help guide the design of medical school curriculums in relation to preparedness for internship.

Originality/value: This study was the first of its kind to investigate the similarities and differences between student placements and the AiM program in Australia.

Limitations: Given the retrospective nature of this study, there is a possibility of recall bias. There was a small study population with few participants not taking part in the AiM program.

Keywords: junior doctor preparedness, medical student curriculum, assistant in medicine (AiM)

All authors publish on behalf of the University of Newcastle Academy for Collaborative Health Interprofessional Education and Vibrant Excellence (ACHIEVE) group.

- University of Newcastle School of Medicine and Public Health

- Bond University

- Hunter New England Local Health District

Corresponding author: Dr Madeleine de Carle, University of Newcastle, School of Medicine and Public Health. University Drive, Callaghan NSW 2308, [email protected]

INTRODUCTION

The ‘steep learning curve’ associated with transitioning from medical student to doctor is well established (Sturman, Tan & Turner 2017; Eley 2010; Edmiston et al. 2023; Monrouxe et al. 2018). Not only are junior doctors faced with the complexity of patient care and the increased responsibility and expectations associated with clinical decision-making, but also increasing time pressures, emotional load, self-realisation of areas of clinical incompetence, and the fear of making mistakes (Sturman, Tan & Turner 2017; Edmiston et al. 2023; Monrouxe et al. 2018; Bullock et al. 2013). Universities are, therefore, challenged with both the task of preparing students for a smooth transition into the workforce and providing the foundations to support a long-term career in medicine.

PREPAREDNESS FOR INTERNSHIP

The notion of ‘preparedness’ is nuanced and difficult to characterise but widely agreed to relate to factors including clinical knowledge, confidence, competence and resilience (Padley et al. 2021). Studies from Australian cohorts suggest that 70–80% of graduates feel at least adequately prepared for internship overall; however, this proportion decreases when looking at specific tasks or aspects of the intern role, especially complex clinical tasks such as pain management, fluid assessment, prescribing, managing unstable and deteriorating patients, and implementing advanced life support (Barr et al. 2017; Monrouxe et al. 2018; Australian Medical Council [AMC] 2023; Chan, Hakendorf & Thomas 2023; Padley et al. 2021). While graduates feel confident in communicating with colleagues and patients about simple matters, they feel less capable communicating in complex cases, including responding to workplace bullying and dealing with errors or challenges at work (Padley et al. 2021).

It is important that junior doctors are well prepared for internship, not only for their own sense of professional identity, but also for patients and the health sector more broadly (Monrouxe et al. 2018; Chan, Hakendorf & Thomas 2023). The ‘steep learning curve’ for junior doctors has been described as ‘physically, psychologically, cognitively and emotionally exhausting’ (Sturman, Tan & Turner 2017). Interns often find themselves fighting to cope, which negatively impacts on self-care and increases rates of burnout (Sturman, Tan & Turner 2017; Chan, Hakendorf & Thomas 2023; Padley et al. 2021). In addition, unpreparedness among junior doctors has the potential to negatively impact patient safety, and may lead to adverse patient outcomes (Eley 2010). The commencement of newly graduated doctors has been associated with a transient increase in medication errors, procedural complications, increased length of stay and mortality risk (Jen et al. 2009; Sharma, Proctor & Winstanley 2013; Phillips & Barker 2010; Huckman & Barro 2005; Vaughan, McAlister & Bell 2011). However, these findings have varied across hospitals and countries, and are often limited by confounding factors that are difficult to control for.

FINAL-YEAR MEDICAL STUDENT TRAINING PROGRAMS

Evidence suggests that longitudinal ‘hands-on’ clinical exposure better prepares students for internship than traditional didactic learning (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; Chan, Hakendorf & Thomas 2023; Padley et al. 2021; Edmiston et al. 2023; Kolb 2014). The association between exposure and preparedness is supported by Kolb’s experiential theory that highlights the role of hands-on experience in providing meaning and understanding to otherwise abstract constructs, allowing for reflection, adaptation and construction of a tailored individual approach to clinical scenarios (Kolb 2014; AMC 2023). Application of this concept is especially crucial in the case of medical graduates preparing to undertake their clinical role as first-year doctors.

Internationally, many countries have formalised pre-internship training in their curriculums, whereby students shadow an intern for a short duration prior to graduating medical school. In 1972, New Zealand medical schools adopted a formalised ‘trainee intern’ year. Medical school barrier exams were moved to year 5, allowing year 6 to be occupied by a clinical apprenticeship (Padley et al. 2021; Dare et al. 2009). Some Australian medical schools have introduced a range of final year ‘workplace immersion’ (Sen Gupta et al. 2014) or longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC) models (Walters et al. 2012) in keeping with the goal of improving preparedness for work (Monrouxe et al. 2018; Lachish, Goldacre & Lambert 2016).

The Australian Medical Council (AMC) has recently updated their Standards for assessment and accreditation of primary medical programs, wherein from 1 January 2024 medical students are required to undertake a pre-internship program specifically designed to facilitate a ‘safe transition to internship’ (AMC 2023).

The Joint Medical Program (JMP), from the University of Newcastle and the University of New England, utilises the Embedded Senior Medical Student (ESMS) program for final-year students, developed in 2020 (May et al. 2021). The framework for this curriculum focuses on experience- based learning and competency-based assessment methods. Across two to three rotations of seven to nine weeks, students are placed across four main disciplines: medicine, surgery, critical care medicine (intensive care, anaesthetics) and emergency medicine. Students are also paired with a junior doctor (JMO) who serves as their ‘buddy’ and complete a learning portfolio where they log procedures performed, investigations interpreted, and communication tasks completed. The program aims, in part, to prepare students for skills and tasks required of them as they move into the workforce as interns.

ASSISTANT IN MEDICINE PROGRAM

In Australia, the Assistant in Medicine (AiM) program was introduced in 2020 as part of the New South Wales (NSW) state government response to the COVID-19 pandemic, aiming to bolster the hospital healthcare workforce in anticipation of increased demand (NSW Ministry for Health 2021). The program offers the opportunity for final-year medical students across the state to undertake part-or full-time employment at an inpatient facility alongside their ongoing studies (NSW Ministry for Health 2021). The role of AiMs is site-dependent, but often includes an increased level of responsibility, compared to medical students, including the ability to order pathology and imaging (NSW Ministry for Health 2021).

The Assistant in Medicine evaluation report, investigated the perspectives of AiMs and those working with AiMs (NSW Ministry for Health 2021). From the perspective of students who undertook an AiM role, the experience was largely positive in terms of building skills, confidence and exposure to hospital-based medicine. Common themes included AiMs perceiving their role as different from a typical medical student placement, with greater feelings of usefulness and responsibility as genuine members of the medical team (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; Edmiston et al.2023; McCrossin et al. 2022). Skills learned were often perceived as more practical, as opposed to theoretical, with AiMs believing that they were building more confidence and competence, easing the transition to internship (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; Edmiston et al. 2023; McCrossin et al. 2022). Additionally, as the AiM role is a paid position, students who participated in the program often felt more motivated to be involved members of the team by taking on jobs and learning new skills (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; Edmiston et al. 2023). The majority of health care staff also perceived the AiM role as a positive addition to the workforce, with most JMOs agreeing that having an AiM reduced their workload (NSW Ministry for Health 2021). Both JMOs and senior medical officers believed that an AiM was a different role to a medical student, viewing them as more capable than their peers and providing more practical skills teaching (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; McCrossin et al. 2022). In a survey of hospital staff, over 70% believed that the AiM role was better at preparing students for internship than a standard medical placement, though no additional research to date has aimed to reproduce or further explore these results (McCrossin et al. 2022).

STUDY PURPOSE

Given the AiM program is novel within NSW and Australia more broadly, there is an opportunity to explore whether clinical experience associated with this role improves the sense of preparedness of interns, thus assisting an often-difficult transition into the workforce. There is limited research evaluating the usefulness of the AiM program for final-year students who take on the role. This study aims to explore, through both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis methods, the experiences and associated sense of preparedness for internship of students who took part in the AiM program, as well as those who chose only to participate in the ESMS program. A secondary aim was to investigate whether students perceived that their role as an AiM prepared them for their medical internship differently from their usual role as a medical student.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

The study utilised a mixed-methods design (Creswell & Plano Clark 2017), which combined both quantitative and qualitative data collection, to explore the experiences and associated sense of preparedness for internship of students who took part in the AiM program, as well as those who did not.

PARTICIPANTS

Participants of this study were alumni of the JMP. All participants completed the ESMS program in one of six clinical schools (three urban and three rural) for the duration of their final year of medical school. The position of AiM was available to all final-year medical students and offered as a part-time or full-time contract of 5–32 hours per week. Students who undertook the AiM program did so at the same clinical site where they completed the ESMS program. The specifics of each role was site-dependent, including the type of shifts AiMs could undertake (e.g., after hours or team-based) and the department they worked within. Participants were included if they had completed their final year of medical school as part of the JMP in 2022 or 2023, and were undertaking their Australian medical internship in 2023 or 2024. Within this cohort, all participants had the opportunity to partake in the AiM program during their final year of medical school. This included a potential study population of approximately 300 students. Participants were excluded if they had not completed their final year of medical school, did not undertake a medical internship in Australia or if there was not a personal email address available for the individual with their respective university alumni service. Eligible participants were identified and contacted via email using the University of Newcastle and New England alumni services.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) via the ACHIEVE network (approval no: H-2023-0224).

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSES

Part 1 (quantitative):

For Part 1 of this project, an online questionnaire was developed by the study investigators and disseminated to the participants as described above. The questionnaire focused on common activities undertaken by medical students and required respondents to indicate whether they undertook these activities on university ESMS placements, during AiM shifts or both (see Supplementary Material Section 1.1).

Data were extracted and descriptive analysis conducted in Microsoft Excel. This included means, standard deviation and frequencies. The small sample size precluded any further statistical analyses. Survey data where participants did not progress beyond the initial two screening questions were excluded (see Supplementary Material Section 1.1, Questions 1a and 1b).

Part 2 (qualitative):

Patterns and trends identified in Part 1 were used to guide the focus group protocol used for Part 2. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted to gain a richer understanding of how the ESMS and AiM programs impacted perceived preparedness for internships. Participants who completed the Part 1 questionnaire were offered the option to participate in Part 2 of the study. The FGD participants provided verbal informed consent at the beginning of the interview. Two FGDs were conducted via the Zoom online platform, led by a junior doctor who is not associated with either university. The structure and questions used during these FGDs are attached in Supplementary Material Section 1.2. These sessions were recorded and transcribed by one of the study investigators (BG).

Thematic analysis was performed utilising the approach described by Saunders et al. (2023), which is specifically written for the health services context (Saunders et al. 2023). Two investigators (MDC and BG) began by reading the transcripts and writing individual summary memos. These memos were then compared between investigators. Both researchers coded both FGD transcripts using NVivo. Semantic, inductive coding was performed (Saunders et al. 2023). The two coders independently established a list of themes and then came together to compare themes. Of the below themes, four out of five were identified by both coders, while one was identified only by BG. The two coders then came together with a third researcher (RB) to discuss and agree on the final set of themes.

RESULTS

For Part 1 of the study, the questionnaire was distributed to 176 recipients (66 from the University of New England and 110 from the University of Newcastle). A total of 78 participants commenced the questionnaire, of which, 58 (74%) completed sufficient questions to be included in the data analysis. For Part 2, 12 participants volunteered to partake in focus groups (seven in focus group A, five in focus group B), generating 158 minutes of data.

STUDY GROUP CHARACTERISTICS

Part 1: questionnaire

Forty-three participants (74%) completed their final year of medical school in 2023, and 15 participants (26%) finished in 2022. All six clinical schools were represented, with most participants attending the two largest urban clinical schools. Most participants (55, 95%) took part in the AiM program.

Those who did not participate cited the AiM program not being available at their clinical site, work and other commitments as reasons for not partaking. AiMs worked a range of 5–32 hours per week in this role, with an average of 18.8 hours per week.

Part 2: focus groups

Eight participants (67%) completed medical school in 2023 and four (33%) finished in 2022. All FGD participants had participated in the AiM program. In contrast to the questionnaire, the majority of participants (7 of 12) were placed at rural clinical skills. Three were at urban clinical schools and two did not identify where they had been placed.

COMBINED RESULTS

Thematic analysis of FGD data identified five themes relating to students’ experiences from the ESMS and AiM programs (Table 1). These themes confirmed patterns and trends identified in Part 1, aligning with the protocol that was informed by the quantitative results. These themes are presented in conjunction with the relevant quantitative survey findings in the following sections. Themes 4 and 5 emerged naturally during FGDs in response to broad questioning about experiences. Themes are presented along with illustrative quotes labelled with the study participant’s demographic characteristics (gender: M/F; year of graduation: 2022/2023). For example, (P1F 2023) refers to Participant 1, Female from the 2023 graduating cohort.

Table 1: combined results

No. |

Focus Group Theme |

SurveyResults Section |

1 |

Exposure to opportunities was dependent on the type of rotation for both AiMs and ESMS students |

'Rotations' |

2 |

Participants functioned more independently as AiMs than as ESMS students |

'Scope of Practice' |

3 |

The variable relationship between exposure and preparedness |

'Skills: ESMS vs AiMs' |

4 |

Participants valued the teaching they received as students |

N/A |

5 |

The AiM program contributed to professional identity formation |

N/A |

SURVEY FINDINGS

Rotations

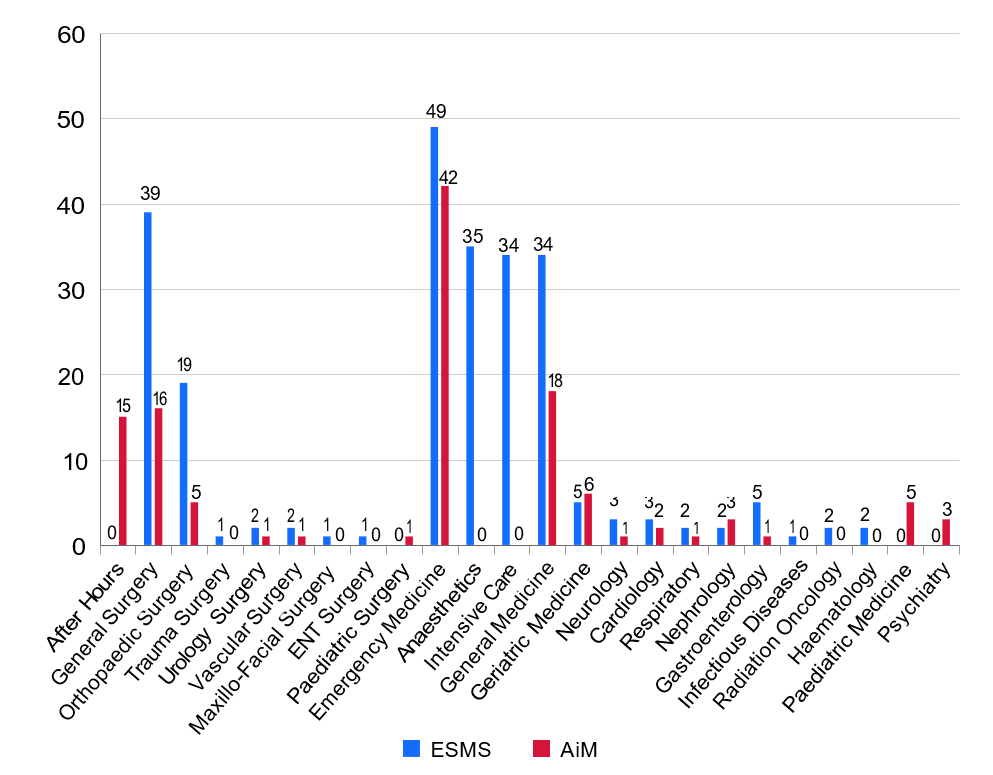

The rotations undertaken by participants reflected those offered as part of the ESMS program (Figure 1). Where students worked as AiMs within a hospital was up to the discretion of the individual health network and hospital. Therefore, participants were allocated across a wide range of areas and specialties, as well as in specific roles including ‘after-hours work’ (Figure 1). Notably, most participants (76%) did at least part of their AiM work in the emergency department (ED) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of study participants in each rotation (ESMS placements vs AiM shifts)

Scope of practice (independence)

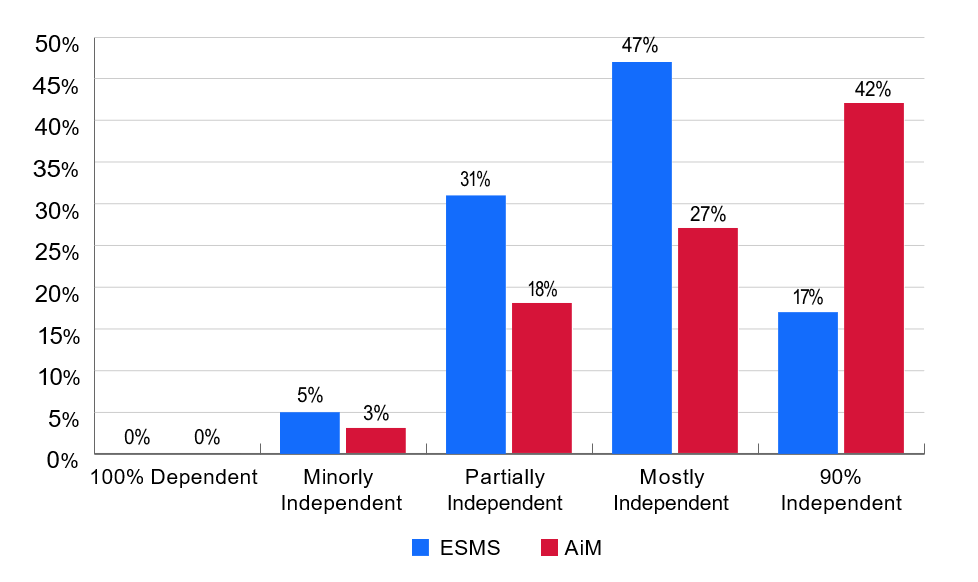

The questionnaire revealed that during ESMS rotations, the majority of participants (47%) were mostly independent (e.g., seeing patients and reporting back to another doctor), with only 17% functioning with 90% independence (Figure 2). In comparison, the majority of those who participated in the AiM program (42%) were 90% independent during AiM shifts, with another 27% mostly independent (Figure 2), representing an overall higher level of independence across AiM shifts compared to student placements.

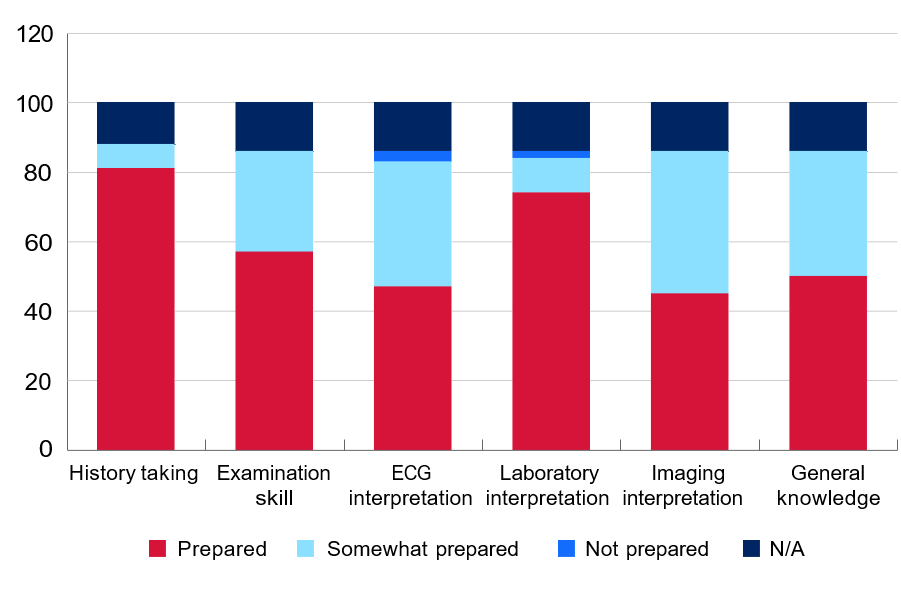

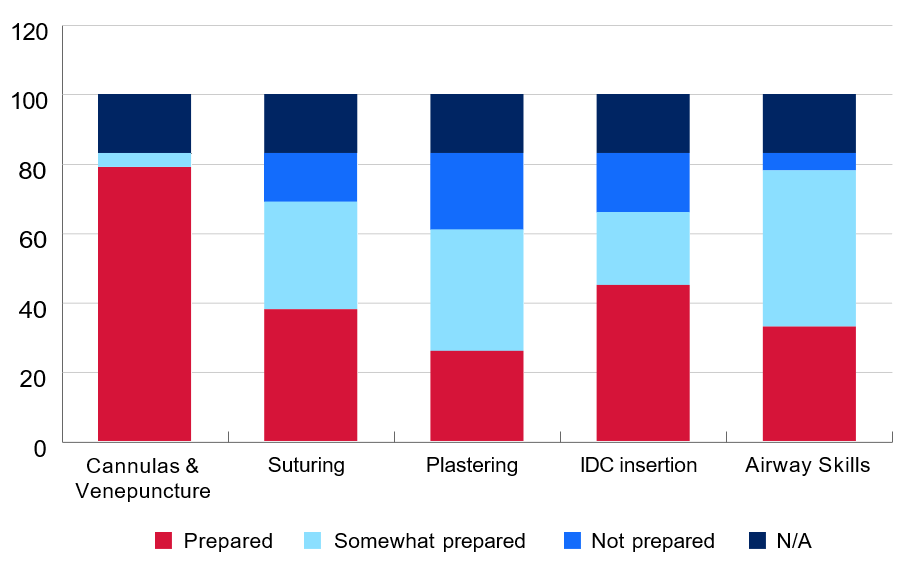

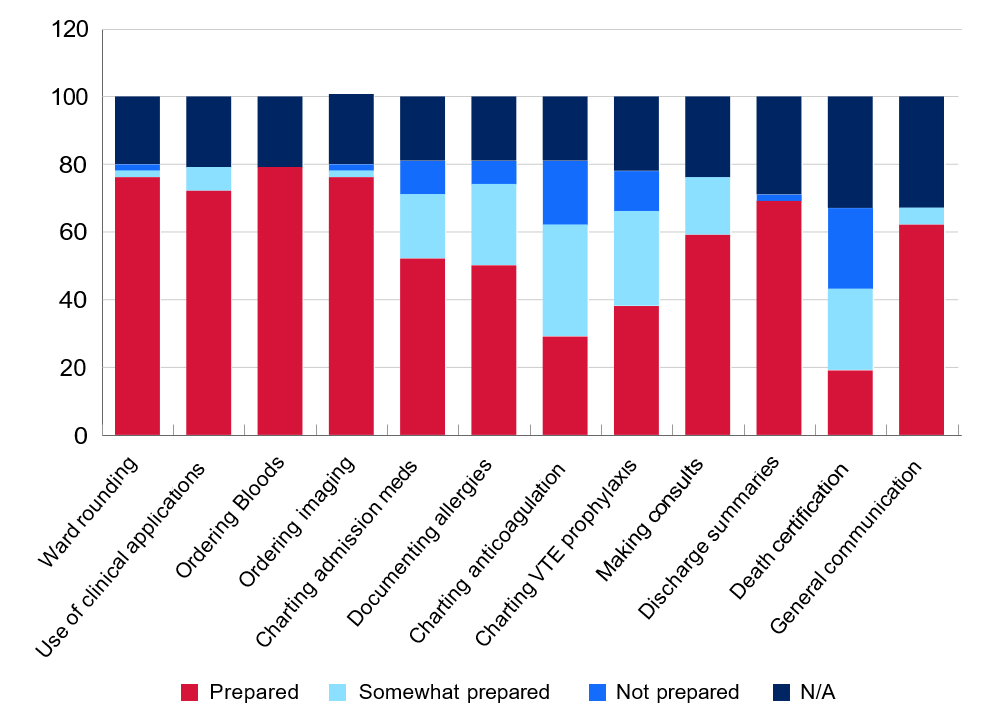

As part of the questionnaire, participants were asked about specific clinical, procedural and ward-based skills and whether they undertook these during ESMS placements, AiM shifts or both. Participants were then asked whether they felt prepared to undertake these skills during their internship. Note that figures referring to preparedness for internship represent the total participant cohort and are not separated into ESMS or AiM subgroups (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Self-rated level of independence (ESMS placements vs AiM shifts)

Skills: ESMS vs AiM

- Clinical skills

The questionnaire revealed that most students undertook all clinical skills (history taking, examination, interpreting electrocardiograms (ECGs), bloods and imaging) as part of their ESMS and AiM positions with experience rates of 70–75% (detailed in Supplementary Material Section 1.3). For most skills, such as history taking, the experience in the skill translated to feelings of preparedness for internship (Figure 3). For other skills, such as ECG interpretation, though >65% of participants had experience in this skill, only 46% felt prepared to use it during internship, with another 42% feeling only somewhat prepared (Figure 3).

Overall, students felt more prepared for general ward work than after- hours work. The average values on a 4-point Likert scale for confidence on commencing internship were 2.7 and 2.1, for ward and after-hours work respectively. Similarly feelings of efficiency in general ward work and after- hours work scored averages of 2.6 and 2.3, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 3: Self-rated level of preparedness for clinical skills during internship

Table 2: Confidence and efficiency at the beginning of internship

| Statement | Average Likert value from 1 (not confident) to 4 (very confident) |

|---|---|

| Confidence in general ward work | 2.7 |

| Efficiency in general ward work | 2.6 |

| Confidence in after-hours work | 2.1 |

| Efficiency in after-hours work | 2.3 |

- Procedural skills:

Overall, participants had a lower level of experience with procedural skills compared to clinical skills. The highest level of experience was gained in the procedural skills of inserting cannulas and venepuncture, with rates of 70–73% as students and AiMs. The other procedural skills had considerably lower rates ranging from 25–65%. There were more participants reporting experience with venepuncture, cannula and in-dwelling catheter (IDC) insertion as an AiM than as a student. Conversely, participants reported more experience as a student than as an AiM with suturing, plastering and airway skills (Supplementary Material Section 1.3). In contrast to clinical skills, for procedural skills there was a stronger association between decreased experience and decreased feelings of preparedness (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Self-rated level of preparedness for procedural skills during internship

- Ward-based skills

Most participants undertook ward-based skills not requiring specialised access to systems (i.e. ward rounding, general use of clinical applications, consults/handover, discharge summaries, communication skills) during both ESMS and AiM placements (Supplementary Material Section 1.3). Ordering of investigations was generally experienced more on AiM placements than ESMS placements, likely reflecting access to specialised systems. There were lower rates, across both ESMS and AiM placements, of charting medications, documenting allergies and experience with anticoagulation and venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, with experience ranging from 15.5–34.5% (Supplementary Material Section 1.3). One skill not undertaken by most participants as ESMS students and as AiMs was death certification. This was reflected in the low levels of self-perceived preparedness for internship (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Self-rated level of preparedness for ward-based skills during internship

FGD Results

- Exposure to opportunities was dependent on the type of rotation for both AiMs and ESMS students

During the focus groups, participants cited that exposure to certain opportunities was more dependent on the location, specialty and type of rotation, than on the participant’s role as a student or as an AiM.

1.1 Exposure was frequently department dependent

Participants stated that more opportunities arose in certain departments, such as emergency departments and orthopaedic rotations, regardless of whether they were in a student or AiM role. This specifically applied to exposure to procedural skills.

‘I did heaps of plastering in ortho clinic. Almost all my ED shifts were AiMs and definitely did a lot of sutures, some local ring blocks, things like that.’ (P8F 2023)

1.2 Exposure was frequently shift-type dependent

Participants identified that different opportunities arose during day shifts compared to after-hours shifts, leading to the gaining of different experience.

‘A lot of our AiMs was after hours, so there’s not heaps of consults that were being made [because of the time of day] more so being a student, prepared me for consults and things like that but all the sort of admin-y stuff I had to learn.’ (P12F 2023)

1.3 Exposure was frequently location dependent

Participants that were based at multiple different rural clinical schools reported more unique experiences and overall greater exposure to skills.

‘I think in Tamworth because you’re on smaller teams and you’re expected to be there every day, most of those skills [referring to specific clinical and procedural skills] were things I would do daily or multiple times a week [as a student on placement].’ (P3F 2022)

‘I was definitely advantaged by the fact that I was in Armidale … I think there is a lot of opportunity to do a lot of clinical skills, procedures, just generally being a bit more independent in rural sites.’ (P8F 2023)

- Participants functioned more independently as AiMs than as ESMS students

Independent practice emerged as a strong theme in FGDs, where participants discussed that they functioned with greater independence as AiMs than as students across a broad spectrum of activities.

2.1 An expectation of independent practice from teams

Participants identified that the structure of the AiM role meant that medical teams expected independent practice without the direct supervision they had as students.

‘I think if it was a simple review, they would expect us [as an AiM] to come up with impressions. But I would always make sure that they were comfortable with the plan, and if I wasn’t sure I would get them to redo the review.’ (P3F 2022)

2.2 Empowered to take opportunities to practice independently

Participants describe a sense of empowerment in the AiM role, where the job encouraged independent practice and taking on greater responsibility.

‘Independence was the most useful part. As a student there’s a lot of things you want to do but are just too afraid to do them. Doing the AiM program pushes you to do them. You do have a choice, but I guess you are given more opportunities to take them on.’ (P4F 2023)

2.3 Independence aided preparedness for internship

The independent practice as AiMs helped participants to feel more prepared for the clinical practice required during internship.

‘Graded independence. So like you had more independence as an AiM than you did as a student, which was a nice intermediary step between being a student and being an intern. It was like a nice little stepping platform.’ [AiM participant] (P12F 2023)

‘But then with AiMs, I think it was the independence and the being... in a way, forced to learn on the job and put into practice things I was hypothetically [learning] as a student, but actually getting to do as an AiM before having to do it as an intern.’ (P3F 2022)

2.4 Independence at times extended beyond skill level

Some participants reflected that the greater clinical independence experienced as an AiM at times resulted in participants practicing above their skill level.

‘We did have quite a few experiences where, say, clinical review would very quickly become a rapid and then you’d be the one calling the rapid and first one there … the worst one we had was me and another AiM, we were the first ones at an arrest, which wasn’t called through properly as an arrest. So we were just running an arrest for 8 minutes by ourselves until someone came, which was definitely way out of our depth at the time.’ (P3F 2022)

- The variable relationship between exposure and preparedness

For some skills, participants felt there was a clearer association between the amount of exposure and feelings of preparedness. For example, participants that had exposure to after-hours shifts as an AiM felt more prepared for after-hours shifts as an intern, whereas those with less exposure referred to this as ‘the steepest learning curve’.

‘I’d done tens of clinical reviews, I’d logged well over 100 cannulas, as an after-hours person, doing those jobs as an AiM. I’d had more experience doing NG tubes, doing catheters and actually performing the skills that you should know as an intern, that wouldn’t have been provided without the AiM program.’ (P6M 2022)

However, for other skills, FGDs revealed that despite exposure, participants did not feel prepared. ECG interpretation was specifically discussed, given the pattern found in the questionnaire (see ‘clinical skills’ section above). During this exploration, some participants felt as though feelings of preparedness were not able to be developed as a student or AiM for skills specifically associated with a high degree of perceived consequence.

‘Probably because you can’t really mess up a death certificate with any true consequence.’ [participant comparing confidence of ECG interpretation to death certification] (P8F 2023)

- Participants valued the teaching they received as students

The consensus from the FGDs was that more of an emphasis was placed on learning as a student than as an AiM. During ESMS placements, participants felt more engaged by their team to focus on theoretical learning and valued the teaching they were receiving as students across multiple platforms. This included informal bedside teaching, for example, the ‘buddy program’ where students were paired directly with a JMO, as well as formal teaching, such as simulation sessions. In comparison, participants felt that as AiMs they had a responsibility to prioritise working over theoretical learning.

‘Being buddied with an intern and someone who was already in the role. I had a really great resident who is really smart and really good friend of mine now and was very involved and wanted me to learn how to be an intern. I think that can vary from person to person depending on who your intern is. But for me, that was probably the best part of preparing to be an intern.’ (P3F 2022)

‘I thought that [simulation labs] was an incredibly effective way to learn, and in a safe and experimental environment where it’s not an actual patient’s life you are dealing with. So that is very helpful.’ (P12F 2023)

‘I did less clinical work and far more paperwork as an AiM. I feel like it was a lot of the time you were there to do paperwork and not to learn. Like if you were there as a student, you were there to learn. If you were there as an AiM, you were to get tedious jobs done.’ (P9F 2023)

- The AiM program contributed to professional identity formation

Participants reflected on the AiM program contributing to their sense of professional identity as a result of increased responsibility, increased independent practice and providing a meaningful contribution to the health service.

‘Because you’re getting paid, I feel like I was held more responsible for the work I produced.’ (P5F 2023)

‘As an AiM, I think it was the more independence and trust that the team had with you so then you could practice more things and still feel, like, comfortable doing it because like you’re not really a doctor yet so if you need to ask for help no one will worry about that.’(P1F 2023)

‘It also allowed us to take a weight off the JMOs, who were trying to cover those after-hours shifts as well, so that we got the better experience, we were doing a job that was actually useful and it was better for the health system in that we could get to things faster and more effectively allow the JMOs to perform their jobs after hours.’ (P6M 2022)

‘I guess just staying for the full amount of hours. I think as a student it’s pretty common to leave before the end of the day, whereas if you’re being paid, you’re obviously staying until the end of the day so I probably saw a lot more as an AiM than I would have just as a student. So that was valuable for coming into the actual job this year.’ (P9F 2023)

DISCUSSION

The AiM program provided a valuable opportunity for final-year medical students to expand their scope of practice and experience a ‘pre-intern’ role prior to commencing employment. Through its mixed-method design, the aim of this study was to explore the experiences and associated sense of preparedness for internship of students who took part in the AiM program, as well as those who did not. While the survey data suggests that ESMS students and AiMs have similar exposures to tasks and procedures, FGDs revealed key differences between the roles in terms of level of independence, type of work performed, sense of responsibility and opportunities to receive teaching.

AiMs were found to practise at a higher level of independence than ESMS students, despite no additional training or experience being required for this role. Both data sources in this study highlighted the AiM program’s role in fostering independence and professional identity.

AiMs cited an increased sense of responsibility as employed members of the team. Across the literature, AiMs have reported feeling more ‘a part of the team’, as medical students often do not have a specific role within a team in terms of delegated tasks and responsibilities (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; Edmiston et al. 2023; McCrossin et al. 2022). This sense of responsibility encouraged AiMs to consider the quality of their work, as well as the benefit it offers their JMO peers and the broader health care system (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; Edmiston et al. 2023).

In addition, JMOs viewed AiMs as more capable than medical students and possibly were more likely to delegate tasks to them knowing they were being remunerated and had rostered hours (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; Edmiston et al. 2023). This was reflected in FGDs, where participants reinforced that being in a paid role increased expectations from other clinical staff (Edmiston et al. 2023).

Also, the type of work associated with AiMs, such as after-hours shifts, may have provided more opportunity for independent practice (NSW Ministry for Health 2021). However, as AiMs are still students with restricted practice and limited clinical experience, the level of independence should not be so great as to place AiMs in inappropriately stressful clinical situations, as described by some FGD participants. This concern was raised in the AiM evaluation report, where 56% of surveyed consultant supervisors believed that AiMs should not work after-hours shifts due to lower levels of supervision and lack of experience in managing work independently (NSW Ministry for Health 2021). However, as in the evaluation report, participants in this study found after-hours exposure a largely positive experience, despite occasional stressful situations (NSW Ministry for Health 2021). Therefore, the benefits and potential negatives associated with after-hours shifts should be considered and balanced when designing medical student placement programs.

One benefit offered in FGDs of attending placements as a student was the increased availability of clinical teaching. In particular, regular simulation sessions provided a safe and controlled environment in which students could practice clinical formulation and management. Extensive research has been conducted into the utility of simulation-based medical education, suggesting that students obtain improved knowledge retention, confidence, performance and communication skills compared with traditional learning techniques, likely preparing them better for clinical practice (McInerney et al. 2022; Elendu et al. 2024; Owen 2012; Datta,Upadhyay & Jaideep 2012). In our FGDs, participants felt that as AiMs they had less exposure to teaching due to the expectation from their clinical teams that they were there ‘to get tedious jobs done’ (P9F 2023). This is contradictory to previous literature, where the AiM program was considered an enhanced learning opportunity compared to standard medical placement (NSW Ministry for Health 2021; McCrossin et al. 2022; Edmiston et al. 2023; Rupasinghe, Majeed Omar & Berling 2023). This discrepancy may exist due to the broad nature of learning that occurs on clinical placement, including both acquisition of theoretical knowledge and ‘hands-on’ job-ready skills. The AiM role is potentially beneficial when it is supplementary to traditional medical student teaching, in line with Kolb’s experiential learning theory (Kolb 2014). While ESMS placements may be richer in theoretical learning, discussions from our focus groups suggest that the AiM program supports the teaching of unexamined skills such as how to manage a junior doctor’s workload. Being taught to ‘think, act and feel’ like a doctor is an important part of medical education, as it supports professional identity formation (Cruess, Cruess & Steinert 2019).

One unexpected finding from the focus groups was the advantages perceived by participants who were placed at rural clinical sites. Participants suggested that being based at a rural clinical school offered valuable pre-internship experience, with smaller clinical teams, and greater clinical exposure and procedural experience. Similar to after-hours shifts, rural placements provided unique opportunities and challenges, influencing both skill exposure and professional growth. This is supported by existing literature, where students from rural placements have been shown to have greater confidence in procedural and clinical skills, as well as improved clinical reasoning, compared to students from urban centres (Rudland et al. 2011; Young, Rego & Peterson 2008; Hepburn et al. 2024). Rural placement experience has also been shown to support preparedness for practice by improving clinical decision-making, autonomy and the ability to work independently (Hepburn et al. 2024; Daly et al. 2013; Furness, Tynan & Ostini 2020).

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

This study contributes to three major areas of research. Firstly, it highlights the existing strengths of the ESMS medical curriculum for final-year medical students. Specifically, the exposure to skills, grounded in an experience-based program, the JMO ‘buddying’ system and the simulation sessions. Both data sources highlight that preparedness for internship is skill-specific, with stronger links to experience for procedural skills than for clinical tasks. In particular, ED placements were cited in survey results and FGDs as providing useful procedural exposure, with most participants completing at least part of their AiM role in an ED. Unique benefits of the AiM program include exposure to a variety of shift types (e.g. after-hours shifts), opportunities for more independent practice and providing a defined role within the medical team. Further research should examine whether these results are replicated across larger cohorts and multiple clinical sites, with subsequent consideration as to whether these aspects of the AiM program should be integrated into medical curriculums.

Secondly, this study contributes to the growing body of literature investigating the impact of the AiM program on students. As the continuation of and ongoing funding for the AiM program is discussed, further longitudinal prospective research into the impact of the AiM program on junior doctors is essential to build upon the findings of this research. In addition, the impact of the AiM program on the healthcare systems they work within, though not within the scope of this study, represents an important future area of research.

Thirdly, though not a direct aim of this study, the focus groups revealed perceived differences between metropolitan and rural medical student and AiM placements. Though a small study population, rural participants noted several positive aspects of being placed at rural clinical sites. Further research into the different experiences of JMP students placed at rural clinical schools could identify site-specific aspects that are beneficial for intern preparedness.

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

This study was the first of its kind to investigate the similarities and differences between student placements and the AiM program in Australia. It used a mixed-methods research design to evaluate the impact of these programs on participants’ self-perceived preparedness for internship.

However, the retrospective nature of the study resulted in participants often reflecting on past experiences, producing possible recall bias. The study population included only a small sample size, particularly with respect to the focus groups. Sample size limited the ability to perform extensive statistical analyses of survey data. In addition, most participants who participated in the questionnaire, and all those who participated in the FGDs, undertook the AiM program. There was also a disproportionate number of participants in the focus groups who attended a rural clinical site in comparison to the JMP cohorts overall.

Several of the study investigators were JMP alumni and had participated in the AiM program. This potential source of bias was reduced as an independent researcher led the FGDs.

CONCLUSION

The importance of developing a sense of preparedness for internship during the final year of medical school is well founded. The AiM program seems to offer students increased exposure to skills, graded independence and an enhanced sense of professional identity, all of which contribute to an increased sense of preparedness. However, the AiM role can also prioritise workforce supplementation over learning, an important experience valued by students, and delegate a demanding level of independent responsibility on AiMs. Further research exploring the various aspects of the AiM program should be utilised to help guide the design of medical school curriculums in relation to preparedness for internship.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the student participants for their contribution to this project.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Newcastle Academy for Collaborative Health Interprofessional Education and Vibrant Excellence (ACHIEVE) network. This source of funding did not contribute to or influence the research project. The authors state there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of data and materials statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation and design of this study. BMA and RB conducted the statistical analysis. MDC and BG conducted the qualitative analyses. All authors contributed to the development of this manuscript, revised the content and have approved the final version for publication.

References

Australian Medical Council Limited 2023, Standards for assessment and accreditation of primary medical programs , AMC, Canberra.

Barr, J, Ogden, KJ, Rooney, K & Robertson, I 2017, 'Preparedness for practice: the perceptions of graduates of a regional clinical school', The Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 206, no. 10, pp. 447-52, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.5694/mja16.00845

Bullock, A, Fox, F, Barnes, R, Doran, N, Hardyman, W, Moss, D & Stacey, M 2013, 'Transitions in medicine: trainee doctor stress and support mechanisms', Journal of Workplace Learning, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 368-82, viewed 4 July 2025, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ jwl-jul-2012-0052/full/html

Chan, JEZ, Hakendorf, P & Thomas, JS 2023, 'Key aspects of teaching that affect perceived preparedness of medical students for transition to work: insights from the COVID-19 pandemic', Internal Medicine Journal , vol. 53, no. 8, pp. 1321-31, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imj.16146

Creswell, JW & Plano Clark, VL 2017, Designing and conducting mixed methods research , SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. Cruess, SR, Cruess, RL & Steinert, Y 2019, 'Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles', Medical Teacher , vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 641-9, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/014215 9X.2018.1536260

Daly, M, Perkins, D, Kumar, K, Roberts, C & Moore, M 2013, 'What factors in rural and remote extended clinical placements may contribute to preparedness for practice from the perspective of students and clinicians?', Medical Teacher, vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 900-7, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.820274

Dare, A, Fancourt, N, Robinson, E, Wilkinson, T & Bagg, W 2009, 'Training the intern: the value of a pre-intern year in preparing students for practice', Medical Teacher, vol. 31, no. 8, pp. e345-50, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590903127669

Datta, R, Upadhyay, K & Jaideep, C 2012, 'Simulation and its role in medical education', Medical Journal, Armed Forces India, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 167-72, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60040-9

Edmiston, N, Hu, W, Tobin, S, Bailey, J, Joyce, C, Reed, K & Mogensen, L 2023, '"You're actually part of the team": a qualitative study of a novel transitional role from medical student to doctor', BMC Medical Education, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 112, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12909- 023-04084-9

Elendu, C, Amaechi, DC, Okatta, AU, Amaechi, EC, Elendu, TC, Ezeh, CP & Elendu, ID 2024, 'The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: a review', Medicine, vol. 103, no. 27, p. e38813, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000038813

Eley, DS 2010, 'Postgraduates' perceptions of preparedness for work as a doctor and making future career decisions: support for rural, non- traditional medical schools', Education for Health, vol. 23, no. 2, p. 374, viewed 4 July 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20853241

Furness, L, Tynan, A & Ostini, J 2020, 'What students and new graduates perceive supports them to think, feel and act as a health professional in a rural setting', The Australian Journal of Rural Health , vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 263- 70, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12607

Hepburn, S-J, Fatema, SR, Jones, R, Rice, K, Usher, K & Williams, J 2024, 'Preparedness for practice, competency and skill development and learning in rural and remote clinical placements: a scoping review of the perspective and experience of health students', Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice , viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10459- 024-10378-4

Huckman, R & Barro, J 2005, Cohort turnover and productivity: the July phenomenon in teaching hospitals , National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, viewed 4 July 2025, http://www.nber.org/papers/w11182

Jen, MH, Bottle, A, Majeed, A, Bell, D & Aylin, P 2009, 'Early in-hospital mortality following trainee doctors' first day at work', PloS One, vol. 4, no. 9, p. e7103, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007103

Kolb, DA 2014, Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development , 2nd edn, Pearson FT Press, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Lachish, S, Goldacre, MJ & Lambert, T 2016, 'Self-reported preparedness for clinical work has increased among recent cohorts of UK-trained first-year doctors', Postgraduate Medical Journal, vol. 92, No. 1090, pp. 460-5, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133858

May, J, Grotowski, M, Walker, T & Kelly, B 2021, 'Rapid implementation of a novel embedded senior medical student program, as a response to the educational challenges of COVID-19', International Journal of Practice- Based Learning in Health and Social Care , vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 63-73, viewed 7 December 2024, https://publications.coventry.ac.uk/index.php/pblh/article/view/736

McCrossin T, Dutton T, Payne K, Wilson R, Bailey J 2022, 'AiMing High in regional Australia: will the medical education response to COVID-19 transform how we prepare students for internship?', Research Square [preprint], viewed 1 July 2023, http://dx.doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1825359/v1

McInerney, N, Nally, D, Khan, MF, Heneghan, H & Cahill, RA 2022, 'Performance effects of simulation training for medical students -a systematic review', GMS Journal for Medical Education, vol. 39, no. 5, p. Doc51, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma001572

Monrouxe, LV, Bullock, A, Gormley, G, Kaufhold, K, Kelly, N, Roberts, CE, Mattick, K & Rees, C 2018, 'New graduate doctors' preparedness for practice: a multistakeholder, multicentre narrative study', BMJ Open , vol. 8, no. 8, p. e023146, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023146

NSW Ministry for Health 2021, Assistant in Medicine evaluation report , NSW Government, viewed 4 July 2025, https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/workforce/ medical/Publications/aim-evaluation-report.pdf

Owen, H 2012, 'Early use of simulation in medical education', Simulation in Healthcare , vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 102-16, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182415a91

Padley, J, Boyd, S, Jones, A & Walters, L 2021, 'Transitioning from university to postgraduate medical training: A narrative review of work readiness of medical graduates', Health Science Reports, vol. 4, no. 2, p. e270, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.270

Phillips, DP & Barker, GEC 2010, 'A July spike in fatal medication errors: a possible effect of new medical residents', Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 774-779, viewed 4 July 2025, https://pubmed. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20512532/

Rudland, J, Tordoff, R, Reid, J & Farry, P 2011, 'The clinical skills experience of rural immersion medical students and traditional hospital placement students: a student perspective', Medical Teacher, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. e435-9, viewed 4 July 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21774640/

Rupasinghe, S, Majeed Omar, M & Berling, I 2023, 'Final year medical students as Assistants in Medicine in the emergency department: a pilot study', Emergency Medicine Australasia: EMA, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 600-4, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.14173

Saunders, CH, Sierpe, A, von Plessen, C, Kennedy, AM, Leviton, LC, Bernstein, SL, Goldwag, J, King, JR, Marx, CM, Pogue, JA, Saunders, RK, Van Citters, A, Yen, RW, Elwyn, G, Leyenaar, JK & Coproduction Laboratory 2023, 'Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis', BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), vol. 381, p. e074256, viewed 4 July 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/37290778/

Sen Gupta, T, Hays, R, Woolley, T, Kelly, G & Jacobs, H 2014, 'Workplace immersion in the final year of an undergraduate medicine course: the views of final year students and recent graduates', Medical Teacher, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 518-26, viewed 4 July 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.31 09/0142159X.2014.907878

Sharma, V, Proctor, I & Winstanley, A 2013, 'Mortality in a teaching hospital during junior doctor changeover: a regional and national comparison', British Journal of Hospital Medicine, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 167-169, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2013.74.3.167

Sturman, N, Tan, Z & Turner, J 2017, '"A steep learning curve": junior doctor perspectives on the transition from medical student to the health-care workplace', BMC Medical Education, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 92, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0931-2

Vaughan, L, McAlister, G & Bell, D 2011, '"August is always a nightmare": results of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and Society of Acute Medicine August transition survey', Clinical Medicine , vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 322-6, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine .11-4-322

Walters, L, Greenhill, J, Richards, J, Ward, H, Campbell, N, Ash, J & Schuwirth, LWT 2012, 'Outcomes of longitudinal integrated clinical placements for students, clinicians and society', Medical Education , vol. 46, no. 11, pp. 1028-41, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365- 2923.2012.04331.x

Young, L, Rego, P & Peterson, R 2008, 'Clinical location and student learning: outcomes from the LCAP program in Queensland, Australia', Teaching and Learning in Medicine , vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 261-266, viewed 4 July 2025, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10401330802199583